It’s spring in northern California. In the past week, birdsong has appeared after a couple of months of near silence. That’s earlier than I’ve heard it before. Meanwhile new record high temperatures are being set. Scanning the science journals, I find these interesting papers on bird populations, climate change, and speciation:

- In the current issue of Proceedings of the Royal Society B, a paper assessing how the earlier onset of spring has affected 117 European migratory bird species during the past past five decades. There’s concern in the world of conservation biology that the ever earlier arrival of spring may be costing migrants their traditional livelihoods because they’re arriving too late on their breeding grounds. This phenomenon is called ecological mismatch. It occurs, say, when migrants arrive after the insects they need to feed their young have already hatched and dispersed. Or after the flowers they feed on have already bloomed and wilted. The authors used accumulated winter and spring temperatures (degree-days) as a proxy for the timing of spring biological events. They found that migrants, particularly those wintering in sub-Saharan Africa, now arrive at higher degree-days, accumulating a ‘thermal delay.’ Species with greater thermal delays have suffered larger population declines. From the paper:

[T]his evidence was not confounded by concomitant ecological factors or by phylogenetic effects. These findings provide general support to the largely untested hypotheses that migratory birds are becoming ecologically mismatched and that failure to respond to climate change can have severe negative impacts on their populations.

Aquatic warbler (Acrocephalus paludicola). Photo by S. Seyfert, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Aquatic warbler (Acrocephalus paludicola). Photo by S. Seyfert, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

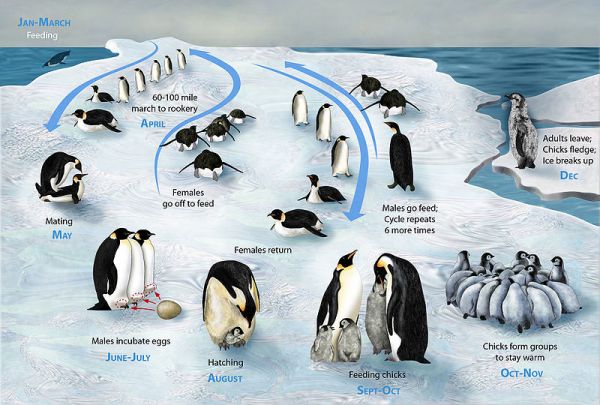

- A new paper in Polar Biology summarizes what we currently know about the numbers of emperor penguins—those March of the Penguins birds—who breed in the dead of winter in Antarctica. There’s a lot we don’t know. We’re still discovering where all their colonies are located. The total number of breeding pairs is unknown, as is the total population. Yet the IUCN Red List categorizes the species as ‘least concern,’ claiming the global population appears to be stable. The author notes the fail:

[This paper] examines what is known about the state of various colonies and demonstrates that currently available data are inadequate for a trend assessment of the global population.

Life cycle of emperor penguins. Image: Zina Deretsky, National Science Foundation.

Life cycle of emperor penguins. Image: Zina Deretsky, National Science Foundation.

- In another paper in the current Proceedings of the Royal Society B, the authors examine differences in the genes and the appearances of magnificent frigatebirds—those huge sailors of the tropical seas. In particular the researchers investigated whether the frigatebirds of the Galapagos Islands have become genetically isolated from others of their kind, or if ocean highways have kept them connected. The data showed plenty of genetic mixing among magnificent frigatebirds of Central and South America, “even across the Isthmus of Panama, which is a major barrier to gene flow in other tropical seabirds:”

In contrast, individuals from the Galapagos were strongly differentiated from all conspecifics, and have probably been isolated for several hundred thousand years. Our finding is a powerful testimony to the evolutionary uniqueness of the taxa inhabiting the Galapagos archipelago and its associated marine ecosystems.

Magnificent frigatebird (Fregata magnificens). Photo by John Picken, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Magnificent frigatebird (Fregata magnificens). Photo by John Picken, courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Finally, in The Birds, Alfred Hitchcock never really told us what was pissing off the gulls and crows of Bodega Bay. He based the film on a 1952 novella by Daphne du Maurier, in which she implied the birds were riled by the East Wind, a metaphor for communism. Here’s a 100-second recut of The Birds. Judge for yourself what’s annoying them. I think it’s the whistling.

The papers:

- Nicola Saino, et al. Climate warming, ecological mismatch at arrival and population decline in migratory birds. 2011. Proc. R. Soc. B.

- Barbara Wienecke. Review of historical population information of emperor penguins. 2011. Polar Biology. DOI: 10.1007/s00300-010-0882-0

- Frank Hailer, et al. Long-term isolation of a highly mobile seabird on the Galapagos. 2011. Proc. R. Soc. B. DOI: