Most experts agree that slowing climate change is going to have to involve some kind of price on carbon dioxide pollution. Although the last attempt to pass a federal carbon price in the US failed in 2009, some of the world’s most-polluting companies haven’t let down their guard. A report last week from the nonprofit Carbon Disclosure Project found that 29 companies that operate or are headquartered in the US are planning for the future by using their own internal carbon price.

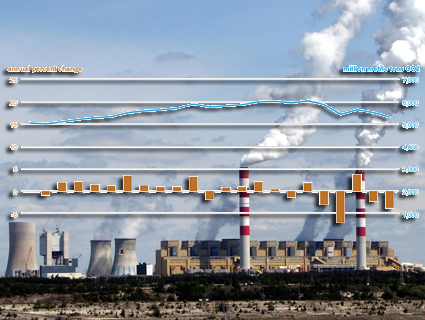

So how much do these companies think carbon pollution is worth? Not every company released a specific number, but we plotted those that did on the chart above. As you can see, there’s quite a broad range, with the price officially recommended by the Obama White House ($37 per metric ton of carbon) falling north of the middle. For comparison, we also included the current prices in British Columbia (which levies a flat tax) and the European Union (which operates a carbon credit-trading market). An oversupply of credits on the EU market has recently driven the price to record lows, below where most economists believe it can be effective in curbing emissions. But a decision yesterday by the European Parliament to slash the number of available credits is expected to drive the price up 35 percent over the next year.

For most companies, the purpose of adding a hypothetical carbon tax to their balance sheets is to prepare for what could become a significant expense in the future. This is especially true for energy companies that produce large amounts of carbon pollution and would therefore be hit hardest by a carbon price; ExxonMobil, with the highest reported internal price, is the world’s second-biggest corporate carbon polluter, while non-energy companies like Walt Disney and Microsoft reported lower internal prices. Zoe Tcholak-Antitch, a spokesperson for CDP North America and its former director, said working on the assumption of a high carbon price is “a very prudent approach” for big energy producers, because it builds a degree of flexibility into their budgets.

“ExxonMobil invests billions of dollars in energy projects which take decades to plan and execute,” company spokesperson Alan Jeffers said in a statement. “For the purposes of our business planning we assume that governments will continue to gradually adopt a wide variety of more stringent policies to help stem greenhouse gas emissions.”

In other words, the company isn’t actually shelling out $60 for each ton of carbon it emits, but the bottom line ExxonMobil brass see in revenue projections for the future accounts for the price as if it was. That way, if and when a price is set, the company’s balance sheet will be prepared to absorb even a relatively high new cost.

And “if the market chooses a lower price, it makes it that much easier” to accommodate, Tcholak-Antitch said.

For at least one of the companies, there wasn’t much of a choice: Xcel Energy, an electric and natural gas utility, was ordered by the Colorado state utility commission to include a carbon price in a recent proposal for future electricity infrastructure investments. The idea, Xcel spokesperson Mark Stutz said, was to compare the future cost-effectiveness of different sources of energy, including coal, natural gas, wind, and solar; if carbon pricing tomorrow were to make coal all but unaffordable to burn, it might be a better use of ratepayer money today to build a wind farm instead. Although in fact, the company’s analysis found solar and wind to be a better bargain than coal and gas even without a carbon price.

Companies outside the energy sector are playing along, too: The Walt Disney Company reported that its internal carbon price was a product of its policy of purchasing carbon offsets and charging those costs back to its own divisions based on their energy consumption; having a concrete price helps those divisions decide what kinds of sustainability efforts will be most cost-effective. Wells Fargo told CDP that its internal carbon price helps the bank determine how likely it is that clients from carbon-intensive sectors, like energy, will be able to repay loans. And Delta Air Lines said it considers the EU carbon price in setting routes into Europe, and weighs an undisclosed internal price when considering airplane purchases.

The difficulty for US-based companies, CDP’s Tcholak-Antitch said, is that the lack of a clear signal from the US government makes it hard to know exactly where to pin the price, which explains the wide range seen in the graph above.

“Some may be setting a very low price just so that they have something that isn’t zero,” she said.

Since the private sector loves little more than long-term stability, she said, that’s all the more reason for US policymakers to reopen the debate.