<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-101076850/stock-photo-a-huge-pile-of-money.html?src=ROVMO03JB_GVoWvkue62eg-1-10">3d Pictures</a>/Shutterstock

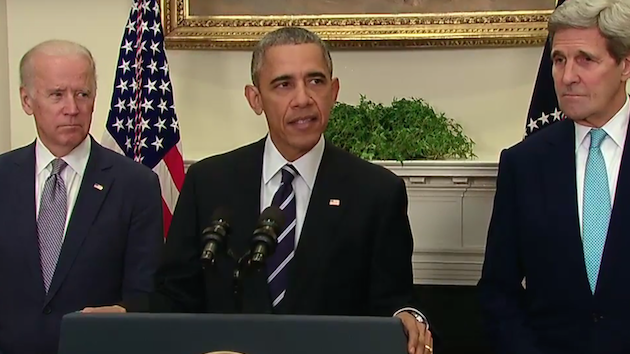

In November, environmentalists were ecstatic when President Barack Obama decided not to grant a permit for the Keystone XL pipeline. But TransCanada, the company behind the project, was not so happy. On Wednesday, it filed a lawsuit against the federal government seeking to overturn the permit rejection. At the same time, it gave notice that it plans to pursue compensation under the North American Free Trade Agreement, to the tune of $15 billion.

In its NAFTA complaint, TransCanada alleges that “the politically-driven denial of Keystone’s application was contrary to all precedent; inconsistent with any reasonable and expected application of the relevant rules and regulations; and arbitrary, discriminatory, and expropriatory.”

In other words, TransCanada thinks it got misled and ripped off by the Obama administration, just to satisfy a wacky cabal of tree huggers. Now, it wants the US Treasury to cough up an apology in cash.

NAFTA is a trade agreement between the United States, Canada, and Mexico that’s meant to protect trade between those countries. One provision of the agreement, Chapter 11, allows a corporation in one country to sue the government of another country if it feels that country’s regulations unfairly discriminate against it. It’s a provision that has always been highly controversial with environmentalists, since it provides an avenue for corporations to contest another country’s environmental policies, as TransCanada is doing now.

That strategy is unlikely to succeed, according to David Wirth, a professor of international trade law at Boston College and a leading expert on international environmental disputes. Wirth said he actually used this very question—could TransCanada win a NAFTA case against the United States?—on a recent exam, and the answer was pretty clearly no. First off, although TransCanada claims to have spent around $3 billion preparing to build the Keystone XL pipeline, it’s not clear that this would actually count as an “investment” that was illegally taken from the Canadian company by the US administration.

“They knew that without the permit approval the project wouldn’t go forward,” Wirth said. “So any money spent in advance is purely speculative.”

Second, although the complaint claims that “environmental activists…turned opposition to the Keystone XL Pipeline into a litmus test for politicians—including US President Barack Obama,” it’s not clear how that really constitutes a legal problem.

“The president, in making a decision in the national interest, has to weigh a variety of factors, including arguments of environmentalists,” Wirth said. “Just because there was political disagreement doesn’t mean the process was defective.”

But most importantly, Wirth said, TransCanada’s complaint doesn’t distinguish between a bureaucratic trade decision that treated a foreign company unfairly—the kind of action NAFTA is supposed to prevent—and a decision made by the president for the benefit of public health and the environment.

“The intent of NAFTA was not to require governments to pay every time they take an action that’s in the public interest,” Wirth said. “It’s very troubling if every time the president makes a decision in the interest of the people, he’s risking an enormous liability of this sort.”

The US has a good track record on NAFTA suits brought by foreign corporations, having lost just one of 14 since the agreement came into effect in 1994. Wirth said NAFTA tribunals have tended to set a pretty low bar for the minimum standard of treatment foreign companies should expect to receive. In other words, TransCanada would have to prove that it was treated exceptionally unjustly by the Obama administration, not just that it had a frustrating experience.

As for TransCanada’s federal lawsuit seeking to reverse Obama’s ruling, the odds for that aren’t great either, since US courts have previously found that cross-border pipelines really are the president’s decision to make, according to Reuters.

Sorry, TransCanada. Maybe try for the permit again in 2017 if a Republican wins the White House. Until then, you might be out of luck.