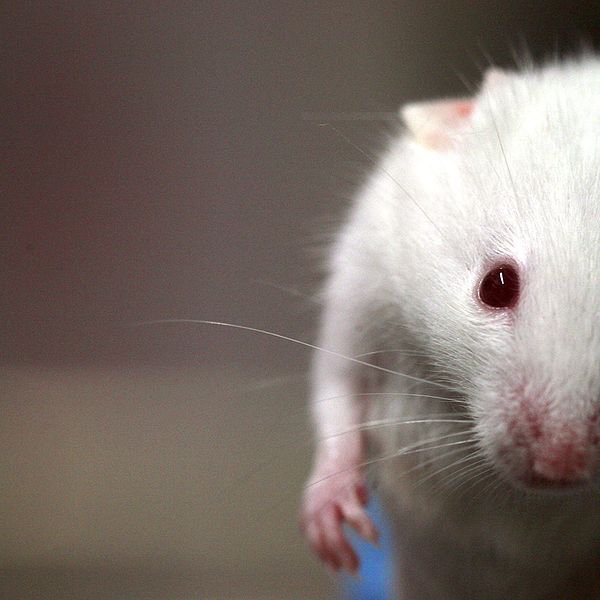

At least in mice. So far. Nature reports on research presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience. Mice fed on a high-fat diet during pregnancy and lactation had larger-than-normal offspring. Those offspring also went on to have larger-than-normal offspring.

At least in mice. So far. Nature reports on research presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience. Mice fed on a high-fat diet during pregnancy and lactation had larger-than-normal offspring. Those offspring also went on to have larger-than-normal offspring.

The 1st-generation offspring also tended to overeat, whether they were fed a high-fat or normal diet. Plus they were insulin-insensitive, a feature of diabetes that often leads to obesity. The 2nd-generation offspring did not overeat, but were large and insulin-insensitive too. Male pups born to mothers on a high-fat diet also transmitted the traits to their own offspring.

The U of Pennsylvania team wants to know which genes were involved in passing on these traits. So far they’ve found epigenetic changes in the hypothalamus, which controls feeding behaviour. Epigenetic changes are biochemical modifications that affect how DNA functions without actually altering its nucleotide sequence. Epigenetic changes can be induced by environmental and/or genetic factors.

The mice in the experiment didn’t get fat, probably because mice don’t tend to fatness. However because overeating predisposes people to obesity, humans would likely get fat in similar circumstances. Therefore if people inherit both a tendency to overeat and insulin insensitivity, the cycle of pathological obesity would be hard to break.

And yet so much more than our individual health depends on it. Skinny stem cells anyone?

Julia Whitty is Mother Jones’ environmental correspondent, lecturer, and 2008 winner of the PEN USA Literary Award, the Kiriyama Prize and the John Burroughs Medal.