Sometime during the preliminary hearings I felt a vast and utter repugnance for the whole bloody shebang and its muddy aftermath; I found myself viscerally unable to read one more word of commentary. I was sick of human behavior, including my own, and of analyses of human behavior. A man with a planed and beautiful face had allegedly killed his ex-wife (a woman with a partygoing face and a spectacular body) and her friend (Ron Goldman, doomed, it would appear, to be an historical footnote; murdered, one might say, twice over).

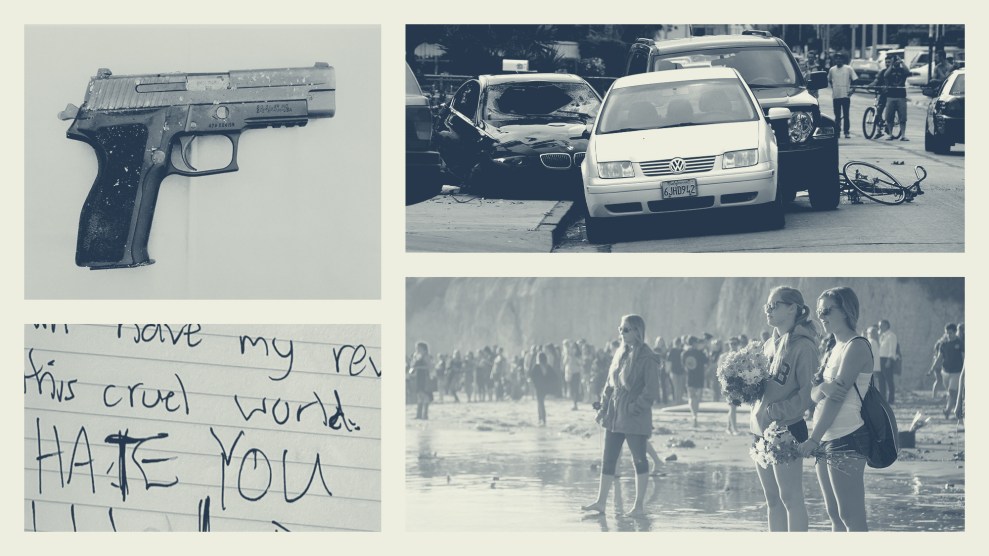

I assumed Mr. Simpson’s guilt on the evidence available to me. Mr. Simpson (you can’t think I will call him O.J.) had hitherto barbarically beaten and terrorized Nicole Brown Simpson–bodybuilding and apparent vacuity not being mitigating factors in her fearful alarm or exculpatory factors in his demented actions–and he had, as a consequence, left behind two innocent children. (Innocent, as regards children, is a redundancy; but the offspring of murdered parents live all their lives in the weird light of ineffable sophistication and blamelessness, the only word for which we can find is innocence.)

My repugnance was indistinguishable from a kind of fever: It was nausea and revulsion; like any illness, it became itself the focus of intense interest to me, so that finally my questions were about myself and not–perhaps I should be embarrassed to admit–about Mr. Simpson or even about his victims, lying (in my forever-stained imagination) in a sludgy river of blood.

I cannot imagine a hand striking flesh. (I spanked my children–I want this to be an exercise in honesty, as it will almost certainly not be an exercise in wisdom–but I mean: punching, slamming, willing to hurt; I mean the force of hatred in the hand . . . or the knife.) To strike flesh is to strike God; God became flesh; flesh is sacred, and–God!–so sweet. How dared he hit her?

May I say, without incurring wrath, that I didn’t like her face? May I also say: So what? Whether she had a “good” face is neither here nor there. I don’t care. I don’t care what she did or didn’t do to incur his deranged anger. Fuck him. He’s a man, isn’t he? Thus, by definition, given to exercising control. So why didn’t he exercise control over his bad self? Don’t tell me he couldn’t. It is the civilized imperative not to give in to acts of savagery–the strong must learn, if necessary, to compensate for their strength, just as the weak have had to learn (pity us all) to compensate for their weaknesses.

I do also heterodoxically believe that women provoke men. We do it with words, and we do it with our bodies. So what? Some women choose not to be weaponless in a world they perceive to be a battlefield in which they are, if not outnumbered, out- or overmanned. And some women have bad characters, just as others have bad tempers. So what? If a woman were a slut and a spendthrift, a tease and a user (and I don’t mean to imply that Nicole Brown Simpson was any of those things), a man is still not allowed to hit her. Period. It is not permissible. If a woman were to get down on all fours and beg for a beating, a man who was truly a man would not oblige. This may be unfair to men. So what. Life isn’t fair, ask any woman. In a folie a deux that involves beating, a man is culpable. Always.

Look: I believe these things to be true. I also admit–at peril to my own psychic balance, to say nothing of my reputation– that I am among those women who experience a certain frisson when a man threatens to apply physical force to me. (Not any man; the man I love.) Oh there will be the Devil to pay if you leave me, he says, halfway in the act of love–adding, God help me, to the thrill. Say that again, woman, he says–I have just accused him of treating me like his white whore–and I will break your beautiful face. . . . His words shock me into sobriety; but I would be lying if I didn’t say that they nourish my belief–I do wish it weren’t so–that he loves me, till death (mine?) do us part. Woman, I am his woman. I yearn to be possessed, to make of two hearts one heart, to make of two bodies one body. I want to break through the walls and the boundaries that separate us; and for that even sex is not absolutely enough. . . .

Simultaneously I yearn to be free. What a dance. I do not wish to hear, I won’t believe it, that a tensile ambivalence is not part of the dynamic of romantic love.

This is the other element that contributes to my vertigo, my nausea: The man I love is black. I am white. Thirty years ago we were lovers. Then, two years ago, we became lovers again. And then he made it impossible for me not to leave him. He left me/I left him: It comes to the same thing–grief, and sadness everlasting. We had, in the days of our joy, a shared mystical belief that if we could make it, anybody could, the world could. An arrogant declension? At its core the belief–we had forded rivers, made bridges, crossed cultures–that a symbolic act, our act, symbolic and material, could save America? Perhaps. Oh, of course. But an irresistible one. And now, in my nausea and vertigo, I say: an antidote to our pain, a reason to live in an insane world.

I have not, since my childhood, been able to see the point of enmity based on color, so silly, so pointless has it always seemed to me. I tell you this not to place myself on the side of the angels; this is a matter, I can only suppose, of temperament and of aesthetics, and I do not deserve nor have I accrued any reward for it. When I was a child, living in Jamaica, Queens, I used, to my family’s shame, to toddle up to black strangers on the bus, caress their skin, and tell them how beautiful they were. If I promised to stop behaving so oddly, so stupidly, I was told, I could have a brown doll to cuddle. So they got me a Little Black Sambo doll. This was not what I’d had in mind. I tore one of its eyes out and with the prongs I carved a deep cut in the offending hand, mine.

. . . When I heard O.J. Simpson’s voice on the 911 tapes I heard my lover’s voice–the color of which, dark mahogany, has been my delight, a melody of arousal. Deep in his throat, clotted with loathing, it was. . . . I have heard my lover’s voice sound like that. My blood, which dances in my veins when he loves me, turns to ice. . . .

. . . I call his cousin, my lover’s cousin, who has affection for me in which I sense a thread of wariness. “They’ll let a black man get so far, and then they cut him down,” she says. They. She means the white world. She means–how can I not finally believe this–me. I start to say: Janie, he cut himself down; Janie, he has white lawyers–the best (of course I think they’re the worst, Alan Dershowitz and F. Lee Bailey being to me the very definition of self-aggrandizement, smarminess, and an absence of discernible principle).

But how can I say these things? Janie has on her side the authority of a suffering I can enter only by proxy. . . . Does suffering authenticate anything more than suffering?

Black women who, in private, excoriate black men, rush to the defense of O.J. Simpson in public, isn’t it odd.

. . . I call my friend Suzanne, who is black. (Earlier Suzanne had called me from St. Croix so that we could celebrate together the victory of Nelson Mandela; we had worked together, in the days of our cutting-a-swath-through-the-Village youth, for the American Committee on Africa; since the massacre in Sharpeville we had worked and then played together and shared the pleasures and the sorrows of our changing days. It was to Suzanne that I had gone when my lover and I parted. I went, a wounded animal, to the person I believed could help me understand, and shelter me, and deal tenderly with my truth, to the person I trusted without reserve.) Suzanne, when I call her about O.J. Simpson, refers me to Cornel West and the concept of “internalized rage.” Internalized? I say. You could hardly get more externalized than Mr. Simpson, I say.

For the first time since I’ve known Suzanne, we are talking at cross-purposes: It seems to me that she feels a degree of sympathy for Mr. Simpson. I do not. Perhaps that means no more than that she is more loving than I, more compassionate. . . . But she would never, has never, allowed herself to be hit, to say nothing of battered; it is she who exhorts me against any tendency to emotional masochism I may harbor. . . . We need to see each other soon, Suzanne and I: When I am with her, the world is not rent. And black is not another country. . . .

Isn’t it all odd. I have been waiting and waiting, but the words white and blonde have not been a featured part of the equation; racism seems not to be what all this is about. Celebrity is what this is about, no? Wouldn’t we treat Joe Namath (or whoever the new hot white football player is) in exactly the same way?

And yet, in a racist country, how could race–his blackness, her whiteness–not be on the agenda? Is it, sub rosa? What does it not infect, after all? Is the very fact that so little has been made of the interracial nature of their marriage proof–as someone told me–that racism is the primary issue? How is it? (No one who espouses this point of view is able coherently to tell me how.)

. . . Unable to sleep, I watch an old Hitchcock TV mystery in the early hours of the morning. It has something, I dimly perceive, to do with sports. At the end, Mr. Hitchcock says: “I am quite the athlete, don’t you know? My favorite sports are chess, falconry, and wife beating.”

What is wrong with men?

My heart hurts. (Nicole, I am sorry I did not like your face. I pray for you. I pray for Ron Goldman. I pray for the children. I am, as a Christian, constrained to pray for Mr. Simpson. I cannot. The words die before they are born.)

Last night, the Fourth of July: a picnic on my roof. My guests wouldn’t allow me to talk of O.J. Simpson, they’d had enough, overdosed. Apocalyptic fireworks lovely as flowers. A hush when I said the forbidden syllables–O.J. Simpson–and at the next table, where a black family sat, heads swiveled. Fireworks: bombs bursting in air.

One of my guests, a college professor, conceded: Maybe this will get that damned term role model out of the language. Yes, please. One remembers when there used to be friends, helpers, advisers, mentors, examples, lovers–even idols, prophets, saints. Why is a man who carries a ball to fame a role model? What exactly is it people thought O.J. Simpson had to teach them? What role?

Does it matter anymore?

Is it too late? We can probably play taps for the niceties of language, too late, too late. As for the human disposition to love–to love across racial lines, to transcend and to exult in differences: Pray God it is not too late. America seems to me now, even more than it did in the days of Birmingham (where, at the spot Bull Connor blew down freedom fighters with water hoses, there is now a park celebrating “Revolution and Reconciliation”), awash in blood. And I ask you to believe that I am not being megalomanic to say that some of it is mine.

I take this personally. So should we all. When people die, possibilities die; we are diminished. When people are murdered, our necessary optimism dies, and, worse, our hope dies. We die. On the morning after the Fourth of July, I ask myself: Please God, is anything possible anymore?

Barbara Grizzuti Harrison is a contributing editor to Harper’s and Mirabella. She is an essayist, journalist, and author of several books, including “Italian Days,” which won the American Book Award.