It’s a classic image: elephants lumbering trunk to tail. But is this docility born of positive reinforcement—or fear of being beaten? Keith Meyers/The New York Times/Redux

It’s a classic image: elephants lumbering trunk to tail. But is this docility born of positive reinforcement—or fear of being beaten? Keith Meyers/The New York Times/Redux

It was a drizzly winter day, and inside the Jacksonville Coliseum, Kenny, a three-year-old Asian elephant, was supposed to perform his usual adorable tricks in The Greatest Show on Earth: identifying the first letter of the alphabet by kicking a beach ball marked with an “A,” twirling in a tight circle, perching daintily atop a tub, and, at the end of his act, waving farewell to the audience with a handkerchief grasped in his trunk.

But Kenny was clearly sick. Elephants are highly intelligent creatures that develop at a similar rate as humans. In the wild, Kenny would still be at his mother’s side, just beginning to wean. In captivity, he was a voracious consumer of water and hay but for the past day or so had showed little interest in either. He seemed listless. Worried attendants in the tent where the elephants were chained between shows twice alerted a circus veterinary technician.

Under federal regulations, sick elephants must get prompt medical care and a veterinarian’s okay before performing. Neither occurred, and at showtime Kenny trotted out to the center ring. He developed diarrhea during the morning show. During the afternoon performance, he began bleeding from his bottom and afterward struggled to stay on his feet. It was only then that Gary D. West, a circus veterinarian, arrived from St. Petersburg to examine the young elephant. West prescribed antibiotics and recommended that Kenny skip the evening show—in a later affidavit, he didn’t stress concern for the elephant’s health but rather that “he might pass some blood which might be seen by a spectator and cause speculation as to his well being.”

West was overruled by Gunther Gebel-Williams, Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey’s legendary golden-haired animal tamer who’d retired from the ring to be vice president of animal care. So Kenny made his third appearance, although he was too weak to perform any stunts.

After the evening show, the bleeding continued. The elephant crew gave Kenny rehydration fluids and shackled him in his stall. Less than two hours later, a night attendant discovered his bloodied body on the concrete floor. The cause of death remains unclear.

Feld Entertainment, Ringling’s corporate parent, did not announce Kenny’s death to the public for nearly a week, until an employee tipped off animal rights activists. They demanded action from the Department of Agriculture, which licenses and inspects circuses under the Animal Welfare Act. Under intense public pressure, including a letter-writing campaign headlined by Kim Basinger, the USDA charged Feld Entertainment with two willful violations for making Kenny perform ill without prompt or adequate veterinary care.

That was in 1998, and at the time it seemed like a turning point in the decades-long fight over circus elephants. For years, animal rights organizations had been releasing horrific undercover videos showing Ringling trainers abusing elephants, but USDA investigations never produced evidence that officials deemed strong enough to warrant action. Now there was a dead body—and a recent precedent. The agency had just fined the King Royal Circus, a small family operation, $200,000 for allowing an elephant to die in an overheated trailer of an untreated salmonella infection.

But after a few months, the USDA announced a settlement. Feld Entertainment would donate $20,000 to elephant causes. In return, the agency absolved the company of blame for Kenny’s death and further declared, “Ringling Bros. has never been adjudged to have violated the [Animal Welfare Act].”

The USDA unwittingly opened a new chapter in the animal rights movement. Frustrated by the agency’s inaction, advocates turned to the federal courts. This shift in strategy has not yet produced a judgment against Feld Entertainment, but it has unearthed an extraordinary trove of records that its lawyers and government regulators had taken great pains to ensure the public would never see; in one notable instance, documents came to light only after a judge threatened to put Feld executives in jail. They include dozens of videos and thousands of pages of investigation files, veterinary records, circus train logs, and courtroom testimony.

Feld Entertainment is a privately held corporation owned by Kenny’s namesake, CEO Kenneth Feld, whose family bought Ringling for more than $8 million in 1967 and folded it into an entertainment empire that includes Ringling’s three year-round touring circus troupes, as well as Disney On Ice, Disney Live, and Monster Jam. Together these shows play for more than 30 million people a year, with annual revenues estimated at between $500 million and $1 billion. But the four-ton behemoths are the biggest draw, generating more than $100 million annually in revenues, according to testimony by Feld executives.

It’s hard not to be captivated. Elephants are smart, social creatures that communicate through a complex score of rumbles, trumpets, and gestures; they also have long memories and the capacity to celebrate, mourn, and empathize.

CEO Kenneth Feld at the circus’ winter quarters Jim Stem/St. Petersburg Times/Zuma Press

CEO Kenneth Feld at the circus’ winter quarters Jim Stem/St. Petersburg Times/Zuma Press

Feld Entertainment portrays its population of some 50 endangered Asian elephants as “pampered performers” who “are trained through positive reinforcement, a system of repetition and reward that encourages an animal to show off its innate athletic abilities.” But a yearlong Mother Jones investigation shows that Ringling elephants spend most of their long lives either in chains or on trains, under constant threat of the bullhook, or ankus—the menacing tool used to control elephants. They are lame from balancing their 8,000-pound frames on tiny tubs and from being confined in cramped spaces, sometimes for days at a time. They are afflicted with tuberculosis and herpes, potentially deadly diseases rare in the wild and linked to captivity. Barack, a calf born on the eve of the president’s inauguration, had to leave the tour in February for emergency treatment of herpes—the second time in a year. Since Kenny’s death, 3 more of the 23 baby elephants born in Ringling’s vaunted breeding program have died, all under disturbing circumstances that weren’t fully revealed to the public.

Despite years of denials, Kenneth Feld has now admitted under oath that his trainers routinely “correct” elephants by hitting them with bullhooks, whipping them, and on occasion using electric prods. He even admitted to witnessing it.

But perhaps more disturbing still is the government’s failure to act. Since Kenny’s death, the USDA has conducted more than a dozen investigations of Feld Entertainment. Inspectors have found baby elephants injured and bound at Ringling’s Center for Elephant Conservation in Florida. Whistleblowers have stepped forward with harrowing accounts of beatings. Activists have released even more videos of elephant abuse, and local humane authorities have documented wounds and lameness.

None of that has moved regulators to action.

Circus oversight rests with the animal care unit in the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. Officials there, as at Feld Entertainment, were not willing to be interviewed. So I called W. Ron DeHaven, who headed the animal care unit from 1996 until 2001 before ascending to lead all of APHIS from 2004 to 2007. (He is now executive vice president of the American Veterinary Medical Association.)

During DeHaven’s tenure at the USDA, a 2005 audit by the department’s inspector general criticized the animal care unit for being too lenient on violators. The report singled out the Eastern region, which oversees Ringling’s operations, for its failure “to take enforcement action against violators who compromised public safety or animal health.”

With an annual budget of only $16 million and 111 employees to monitor nearly 9,000 animal entertainment, breeding, and research facilities, the agency didn’t have the capacity to prosecute many cases, DeHaven explained. He acted on the egregious cases, he said, like King Royal. I asked what made that case worse than others. A dead elephant, he said, and a clear violation.

How was that different than Kenny? DeHaven said he didn’t recall the particulars of that case. But, he added, “You don’t take on an organization like Feld Entertainment without having strong evidence to support it.”

That sentiment was echoed by Kenneth H. Vail, who for decades served as the USDA’s lead legal counsel on animal welfare cases. We met at his red brick townhouse in northwest DC in July, just after his retirement. Thin-faced, with soft eyes and a quiet voice, he invited me in out of the 100-degree heat to talk for more than an hour. He said Feld Entertainment cases received special attention from him and other top department brass. “A case involving a multimillion-dollar company is significant,” Vail said. “There’s a political aspect to Feld cases. The company is a big target for animal rights groups.” True, USDA investigators advocated action against Feld Entertainment on numerous occasions, but Vail said he never felt their evidence could withstand a legal challenge by the company. “There’s no way to control an elephant without an ankus,” and the Animal Welfare Act doesn’t prohibit it, he explained. Maybe a time will come when bullhooks, chains, and “elephants getting paraded around doing unnatural things” is prohibited, he said, but until then, litigating abuse is difficult.

“If I were an elephant, I wouldn’t want to be with Feld Entertainment,” Vail conceded. “It’s a tough life.”

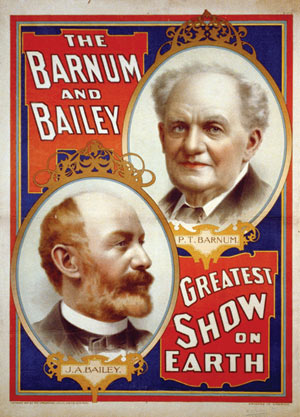

Save for modern sound and lighting systems, today’s circus hasn’t changed all that much from the spectacle created by P.T. Barnum, the corpulent showman who delighted audiences with midget Tom Thumb, faux mermaids, and soprano Jenny Lind (PDF).

Courtesy Library of CongressBy 1850, Barnum also had a traveling menagerie that featured an elephant or two. But he imagined an entire herd, so he dispatched agents to sail to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), where they hired 160 “native assistants” to search the jungles. The most daring waited until an elephant napped against a tree. They would tickle a sensitive spot on the elephant’s hind leg and, when it lifted its foot to shake off the nonexistent insect, slip a noose around its ankle. The expedition “killed large numbers of the huge beasts,” Barnum wrote in an autobiography. But 11 live ones were hoisted into a ship’s hold for the 12,000-mile voyage to New York City. One died en route and was dumped overboard. Barnum paraded the rest down Broadway harnessed to a chariot, and they became the featured attraction of a new traveling show, Barnum’s Great Asiatic Caravan, Museum, and Menagerie.

Courtesy Library of CongressBy 1850, Barnum also had a traveling menagerie that featured an elephant or two. But he imagined an entire herd, so he dispatched agents to sail to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), where they hired 160 “native assistants” to search the jungles. The most daring waited until an elephant napped against a tree. They would tickle a sensitive spot on the elephant’s hind leg and, when it lifted its foot to shake off the nonexistent insect, slip a noose around its ankle. The expedition “killed large numbers of the huge beasts,” Barnum wrote in an autobiography. But 11 live ones were hoisted into a ship’s hold for the 12,000-mile voyage to New York City. One died en route and was dumped overboard. Barnum paraded the rest down Broadway harnessed to a chariot, and they became the featured attraction of a new traveling show, Barnum’s Great Asiatic Caravan, Museum, and Menagerie.

The elephants drew rave reviews—”It is astonishing to think how docile these huge creatures are, when it is remembered that but a brief time since they were running wild in the jungle,” a writer mused in Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing Room Companion—and huge profits. Barnum’s circus grew into ever more elaborate productions, with dangerous cats, prancing horses, legions of clowns, trapezes, high-wires, and three rings under a tent the size of a palace. Barnum joined James Anthony Bailey and then merged with the seven Ringling brothers to make “The Greatest Show on Earth.” The conga line of elephants was the act that crowds most flocked to see.

This was the circus Irvin Feld envisioned when he acquired Ringling in 1967. Feld, born in 1918, got his first taste of circus life as a teenager, selling snake oil (literally) from a card table at carnivals. He became an innovative music promoter, recognizing early on that serious money could be made using sports arenas for concerts and promoting then-unknowns like Chubby Checker and The Everly Brothers. In 1956, when Ringling had lost both luster and financial footing, Feld persuaded Ringling’s grandson to abandon the big top for sports arenas. After 10 years as the circus’ booking agent, he and two partners bought it. John Ringling North cited “their dedication to maintain the concept, tradition, and artistic standards of the circus.” Feld called it “the happiest moment of my life.”

Feld immediately recruited German superstar Gunther Gebel-Williams, “the greatest wild animal trainer of all time,” to help boost lagging ticket sales. Back then, Ringling had just one touring company, the Blue Unit. Feld added the Red Unit to showcase Gebel-Williams and his menagerie of some 20 elephants and 50 big cats. Svelte and handsome, Gebel-Williams would enter the ring bare-chested astride two galloping steeds, send tigers leaping through flames, lead a line of elephants through a tumbling act, cuddle up with panthers, and exit with a leopard draped around his neck—an image memorialized in a 1970s American Express commercial.

Feld seemed on his way to restoring The Greatest Show on Earth to the height of its glory. But outside the ring, times were changing. The movie Born Free, about a couple who raised an abandoned lion cub and then set it free in Kenya, won two Academy Awards the same year that Feld bought the circus. “Animal rights” had entered the popular lexicon. Congress expanded the Animal Welfare Act in 1970, charging the USDA with setting humane standards for treatment of warm-blooded animals by researchers, breeders, and exhibitors—including circuses. In 1973, Congress passed the Endangered Species Act, which barred “harm” or “harassment” of listed animals. Asian elephants made the endangered list several years later, and their import was banned under international conventions. Smaller than their African cousins and generally considered much easier to manage, Asian elephants had for decades comprised the vast majority of Ringling’s stock. The listing effectively shut down the supply line.

By the time Irvin Feld died in 1984, leaving his son, Kenneth, to run the show, animal rights organizations were proliferating. Zoos began adopting an emerging animal management philosophy called “protected contact,” which controls animals with physical barriers instead of sticks and chains. But this was of little use to the circus, where direct interaction between humans and wild beasts is the point. Feld Entertainment faced a conundrum: The audiences still wanted to see elephants—but they wanted to see them treated nicely.

Renowned Ringling Bros. trainer Gunther Gebel-Williams during his 1989 farewell tour Scott McKiernan/Zuma Press/NewscomSo the company poured tens of millions of dollars into PR campaigns that portrayed the elephants as willing performers, as well as legal firepower to keep regulators and activists at bay. Gebel-Williams got a makeover. A press release lauded his “animal training based on mutual respect and positive reinforcement” that “forever changed the standards of animal training.” It’s true that Gebel-Williams had an extraordinary rapport with the animals, but it’s also true that he routinely whipped elephants and struck them with bullhooks. A few months after Kenny’s death, Gebel-Williams was spotted whipping a baby elephant in the face outside a circus train in Mexico City.

Renowned Ringling Bros. trainer Gunther Gebel-Williams during his 1989 farewell tour Scott McKiernan/Zuma Press/NewscomSo the company poured tens of millions of dollars into PR campaigns that portrayed the elephants as willing performers, as well as legal firepower to keep regulators and activists at bay. Gebel-Williams got a makeover. A press release lauded his “animal training based on mutual respect and positive reinforcement” that “forever changed the standards of animal training.” It’s true that Gebel-Williams had an extraordinary rapport with the animals, but it’s also true that he routinely whipped elephants and struck them with bullhooks. A few months after Kenny’s death, Gebel-Williams was spotted whipping a baby elephant in the face outside a circus train in Mexico City.

Nonetheless, the sleight of hand worked. When Gebel-Williams died in 2001, the Sarasota Herald-Tribune‘s obituary noted that he had “substituted humane, positive reinforcement and reward for the fear and force upon which many animal trainers rely.”

The biggest challenge for Feld Entertainment’s “positive reinforcement” campaign was the ubiquitous bullhook or ankus. It’s a malevolent-looking instrument, about three feet long, with a sharp, metal point-and-hook combination at one end. The point is for pushing. The hook, inserted in the mouth or at the top of the ear, is for pulling. Both are sharp enough to pierce elephant hide.

In Rudyard Kipling’s 1894 classic, The Jungle Book, Mowgli finds an ankus and asks the panther Bagheera what it is used for:

“It was made by men to thrust into the heads of [elephants],” said Bagheera. “That thing has tasted the blood of many.”

“But why do they thrust into the heads of elephants?”

“To teach them Man’s Law. Having neither claws nor teeth, men make these things, and worse.”

Feld Entertainment rebranded the ankus as a “guide.” Handlers hid them in their sleeves or carried smaller, less menacing-looking models during the show. As Joan Galvin, the company’s vice president, assured the Associated Press in 1998: “Elephants are one of the most beloved acts that performs in the circus today. Abusive techniques are absolutely prohibited.”

Baby Benjamin’s trainer struck him with a bullhook “all over the head, quite forcefully and repeatedly. It was not pretty.” David Handschuh/New York Daily News/Getty Image

Baby Benjamin’s trainer struck him with a bullhook “all over the head, quite forcefully and repeatedly. It was not pretty.” David Handschuh/New York Daily News/Getty Image

In December of that same year, two attendants on the Blue Unit left the tour during a stop in Huntsville, Alabama. They called a local animal welfare office, explaining they had quit in disgust over the way the elephants were treated. The woman put them in touch with Pat Derby, a former Hollywood trainer who had founded the Performing Animal Welfare Society (PAWS).

With fiery orange hair atop a stout physique, a gravel voice, and a talent for attention-grabbing tactics, Derby had been Ringling’s No. 1 antagonist for more than a decade. Her supporters organized protests outside performances and shot videos of trainers hitting elephants.

Derby arranged for lawyers to take the men’s videotaped depositions and written affidavits. The attendants, Glenn Ewell and James Stechcon, had lived transient, sometimes troubled lives, working off and on for circuses. At Ringling, where they mucked out elephant pens and assisted with feeding, they claimed to have witnessed regular elephant abuse and more than a dozen extended beatings during their three months on the road.

Several of the beatings targeted Nicole, a twentysomething elephant named after Kenneth Feld’s eldest daughter. Sweet-natured but clumsy, Nicole would frequently miss her cues to climb atop a tub and place her feet on the elephant next to her, Stechcon said in his videotaped statement. “I always rooted for her, ‘Come on, Nicole, get up,'” he said. “But we left the show, brought the animals back to their area, and…we took the headpieces off, and as I was hanging them up, I heard the most horrible noise, just whack, whack, whack. I mean, really hard. It’s hard to describe the noise. Like a baseball bat or something striking something not—not soft, and not hard…I turned around to look, and this guy was hitting her so fast and so hard [with the ankus], and sometimes he would take both hands and just really knock her, and he was just doing that. And I was, like, I couldn’t believe it.”

Benjamin, a precocious three-year-old, also suffered frequent beatings from his trainer, Ewell and Stechcon said. Able to balance on a wooden barrel, ride a tricycle, shoot hoops, play musical instruments, and paint a picture by holding a brush with his trunk, Benjamin had appeared on The Today Show and CBS This Morning. His trainer, Pat Harned, told journalists that Benjamin had been trained thanks to rewards of bread or bunches of bananas.

The whistleblowers told investigators that Harned also used force. “Pachyderms want to throw things on their back, it’s a—it’s a genetic response. Anyway, I saw Benjamin, after he was brushed off, take some sawdust and throw it on his back,” Stechcon said. That upset Harned, who “dealt with it accordingly, with a bullhook, striking Benjamin all over the head, quite forcefully and repeatedly. It was not pretty.”

Derby helped the men file a formal complaint to the USDA. In early January, a senior investigator and veterinarian followed up with a surprise visit to the Blue Unit, on tour near Miami. The USDA team found scars and abrasions on several elephants and a fresh puncture wound on another. Another Ringling employee reported treating hook boils—infected bullhook wounds—”twice a week on average.”

But all five trainers and handlers named by Ewell and Stechcon denied abusing elephants or ever seeing anyone else do so. “I have a very good relationship with the elephants, especially the babies Benjamin and Shirley,” Harned told the investigator. “There is no abuse of any of the elephants. I treat these elephants as my children.”

DeHaven, the animal care unit director, received a report from the senior investigator that none of the allegations could be confirmed. But he also received a complaint from the director of the Eastern regional office about the quality of the investigation. She wrote that the investigator hadn’t interviewed the Ringling employees whom the whistleblowers had identified as potential corroborating witnesses, nor had he followed up on the worrisome admission that hook boils were commonplace.

Yet another back-channel note came from Feld Entertainment’s corporate counsel, Julie Strauss. She wrote that the company had dug up a past misdemeanor harassment charge against Ewell and a couple of arrest reports on Stechcon for fighting: “We bring this information to your attention so that you may consider whether it is pertinent to your assessment of the reliability of those two former employees’ allegations.”

Vail advised against proceeding. (“Credibility problem,” he told me.) And DeHaven closed the case, writing that he ultimately was swayed by the vehement denials of the accused trainers.

Meanwhile, DeHaven received alarming reports from the USDA investigators who’d conducted a routine inspection of Ringling’s Center for Elephant Conservation, the $5 million, 200-acre complex the company had opened in 1995 to ramp up its nascent captive breeding program.

On February 9, 1999, two animal care veterinarians arrived and were escorted around by Gary Jacobson, then the center’s director of elephant training and now its head. Their last stop was the night holding barn, where they found two baby elephants, restrained with ropes and chains, barely able to move. The elephants, 18-month-olds named Doc and Angelica, each had lesions on their hind legs and scars from healed injuries.

Courtesy Library of Congress“Gary Jacobson said Doc and Angelica were weaned from their mothers on January 6th and that the scars were from rope burns during this process,” the vets’ report later read. “He described the process as putting a cotton rope around each leg, then a chain around the neck, and leading the baby off with another elephant.”

Courtesy Library of Congress“Gary Jacobson said Doc and Angelica were weaned from their mothers on January 6th and that the scars were from rope burns during this process,” the vets’ report later read. “He described the process as putting a cotton rope around each leg, then a chain around the neck, and leading the baby off with another elephant.”

In the wild, elephants suckle for two to four years and remain under their mother’s care until their late teens to learn social and survival skills—not unlike humans. But Ringling’s elephants can be forcibly removed from their mothers when they are barely more than a year old. (Nearly a decade later in testimony, Jacobson would describe a recent separation of two babies from their mothers this way: “We just grabbed them and tied them up,” one for 10 days and the other for four months—except for 40 minutes of exercise a day.)

The inspectors wanted to cite Ringling; DeHaven concluded, “There is sufficient evidence to confirm the handling of these animals caused unnecessary trauma, behavioral stress, physical harm and discomfort.” Even so, he declined to take action. Instead, he wrote to Feld officials that he felt “certain that you will address this situation to ensure that it does not reoccur.”

It wasn’t even a slap on the wrist, but Feld was still aggrieved. DeHaven finally agreed to downgrade the matter from an “investigation” to a “fact gathering process.”

Two months later, Today Show star Benjamin and a four-year-old named Shirley were being transported by an 18-wheeler from Houston to Dallas when trainer Pat Harned—who’d worked with them since they’d been taken from their mothers—decided to stop overnight at a property owned by the truck driver’s father-in-law. In the morning, Harned let the elephants wander into a pond on the property. A little while later, Benjamin was dead. Harned says when he called to the elephants to get out, Shirley came, but Benjamin just dove underwater and died. Experts hired by Feld eventually surmised that he may have suffered a heart attack, though they puzzled over why such a young, healthy elephant would succumb.

A senior USDA investigator interviewed the other witnesses who said Harned struck Benjamin with his bullhook while he was playing near the shore, which is why he swam into deeper water. “The elephant seeing and/or being ‘touched’ or ‘poked’ by Mr. Harned with a ankus created behavioral stress and trauma which precipitated in the physical harm and ultimate death of the animal,” the investigator wrote his superiors.

Once again, DeHaven and Vail saw no cause to act. “Benjamin? Give me a break,” Vail said when I asked about the incident.

But if the USDA didn’t have enough evidence to suspect that abuse—or fear of it—may have been a factor in Benjamin’s death, it soon would. Tom Rider arrived on PAWS’s doorstep in March 2000. A big man with a wide, friendly face, he’d spent two and a half years feeding and watering elephants on Ringling’s Blue Unit. Eventually, he’d provide a USDA investigator with a seven-page sworn affidavit describing 25 incidents of elephant abuse by more than a dozen members of the Ringling crew.

A year before Benjamin died, Rider said he saw Harned strike the young elephant repeatedly with his bullhook in the presence of the adult elephants. Females are very protective, and Karen, an older elephant, began to clank her leg chains aggressively. Harned stopped hitting Benjamin, the affidavit said. “And then he came over there and he started in on Karen for at least 21 minutes, 23 minutes. He had her, jabbing her under the leg, making her raise her foot up and hold it there, hitting her behind the leg, come up and jabbing her in the side,” Rider later testified. “Hooking on the head and behind the ears. It just went on and on.” Rider also said Nicole was singled out for terrible punishment.

After taking Rider’s affidavit, the investigator added a personal observation: “There is no question that he loves the elephants that he worked with, and wants to help them find a better life than what is provided by the circus.” She also sent a request to her superiors that Nicole be located and examined, and that her medical records be obtained immediately—to no avail.

The agency “has let many people down (as well as Nicole) on being able to truthfully report the disposition and well being of this animal,” the investigator wrote.

Soon after, the case was closed without action.

By early 2000, Derby of PAWS had had enough. She turned to Katherine Meyer, a gregarious blonde who, with her husband, Eric Glitzenstein, ran what Washingtonian magazine called “the most effective public-interest law firm in Washington.” The couple met working for Ralph Nader in the 1980s and, after striking out on their own in the 1990s, scored a string of animal rights victories that caught Derby’s attention.

Meyer proposed that PAWS file a federal lawsuit against Feld Entertainment, seizing on a provision in the Endangered Species Act that allows citizens to sue violators directly. Such citizen lawsuits had been used to protect endangered animals in the wild but not in captivity. A win would revolutionize animal exhibits.

That same spring, two private detectives visited Derby. They explained that they’d been retained by a fired Feld executive to gather evidence of the company’s illicit spying on animal rights groups. The former executive had reportedly stiffed them on their fee, so—for $200,000, records show—they offered up 20 boxes of documents on her organization. The materials included purloined records, weekly surveillance reports, and evidence that two Feld moles had infiltrated PAWS by posing as volunteers; one had gained entry to Derby’s inner circle. There was evidence of similar schemes against the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) and the Elephant Alliance.

It was part of a multimillion-dollar spy operation run out of Feld headquarters to thwart and besmirch animal rights groups and others on the company’s enemies list, according to a stunning Salon piece by Jeff Stein. Feld had even hired Clair George—the CIA’s head of covert operations under President Reagan until his conviction for perjury in the Iran-Contra scandal. (George, who died in August, received a pardon from President George H.W. Bush.)

Derby filed a civil lawsuit against Feld Entertainment for racketeering and fraud on June 8, 2000, in the federal courthouse for the Eastern District of California. About a month later, Meyer filed the elephant lawsuit in the federal district courthouse in Washington, DC. Soon after, lawyers for Feld approached Derby with a generous settlement offer on the spy case. They would donate elephants and cash to her wildlife sanctuary if she dropped the elephant lawsuit and refrained from publicly criticizing Feld Entertainment. She agreed.

But the elephant lawsuit limped along with Meyer remaining lead counsel and Rider and seminal players in the animal rights movement—including the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, the Animal Welfare Institute, the Fund for Animals, and eventually the Animal Protection Institute—as plaintiffs. The case was assigned to US District Judge Emmet Sullivan, a mercurial jurist who quickly tossed the suit for lack of standing; he found that none of the people involved could prove that Feld Entertainment’s actions had caused them harm. (Animals don’t have standing.) The appeals court overruled him in 2003, at which point Meyer subpoenaed government documents and filed discovery requests with Feld Entertainment. Feld stalled for more than a year until the company’s lawyers finally sent word that the records would be delivered on June 9, 2004.

Meyer prepared for a sizable document dump. But at the appointed hour the deliveryman left just two cardboard file boxes of press releases and other innocuous materials. Instead of the detailed veterinary charts Meyer had requested, she got a page or two on each elephant. She pressed, but Feld Entertainment stonewalled.

Meanwhile, the casualties at Ringling were mounting. In early August of 2004, an eight-month-old elephant named Riccardo was euthanized after he broke two legs. A Feld press release explained that he had been playing outside when he climbed, as he often did, onto “a round platform 19 inches high. This time, he lost his balance and fell.” Although Ringling denied it, the activity sounded suspiciously like a training drill. Investigators recommended that Ringling be found in violation for failing to provide adequate care after he fell.

On August 20 and 21, an anti-cruelty activist in Oakland, California, videotaped a Ringling handler repeatedly striking a seven-year-old elephant with a bullhook while it was chained. It was Angelica, the same animal USDA inspectors discovered bound and injured at the Center for Elephant Conservation in 1999. This time, they recommended an $11,000 penalty for excessive force and chaining. A regional USDA director for animal care urged his superiors to take action: “Feld Entertainment is a large corporation with a previous enforcement history.” Then-Illinois Sen. Barack Obama joined the chorus at PETA’s request. The cases landed in Vail’s office, where they hit a dead end.

But Meyer saw an opening. There had been no mention of Riccardo’s birth, let alone death, in the “complete” veterinary records she had received. When Judge Sullivan demanded an explanation, Feld’s lawyers responded that their client had recently found a stash of about 2,100 pages stored in the home of William Lindsay, the company’s chief elephant veterinarian.

“How could you overlook 2,100 pages of documents?” Sullivan thundered. “If I have to march those CEOs in here for explanations under oath and under penalty of perjury I’ll do that…I’m not going to rule out incarceration either. Because I’m sick and tired of all these efforts by litigants to hide the ball…And when I say all, I mean all, every last record.”

Dozens of boxes of medical records promptly arrived at Meyer’s office. Riccardo’s veterinary charts were tucked inside one. He’d been the firstborn of Shirley, the elephant who as a baby swam with Benjamin on the day he died. Subsequently unable or unwilling to perform, Shirley was returned to the Center for Elephant Conservation and was impregnated before her seventh birthday. Elephants enter puberty around 10. In the wild, they practice mothering by babysitting younger elephants, begin breeding in their teens, and give birth surrounded by experienced females who assist and trumpet the calf’s arrival to the rest of the herd.

Shirley gave birth on December 5, 2003, at age eight. She was chained by three legs and surrounded by human handlers, who poked her with bullhooks during labor. When the slippery newborn dropped, trainers whisked him away. Riccardo was placed in the care of center training director Jacobson and his wife. His training started at three months, while he was still being bottle-fed. The couple tied ropes to his trunk and feet to get him to climb on the tub or attempt other tricks. By six months, he developed knee problems. “Not laying down, seems to be uncomfortable,” read a notation by the animal care staff for June 15, 2004. “Left rear leg, knee appears to be swollen.” They administered a painkiller and training resumed. On July 9, 2004, another notation said, “Front leg stiff.” He received a painkiller and training resumed.

Four weeks after that entry, the fatal accident occurred. Testimony would later reveal it wasn’t during play, as Feld Entertainment had contended, but during a training exercise while being pulled by a rope tied to his trunk onto a 19-inch-high tub.

One of the problems bedeviling the plaintiffs was their inability to line up an elephant veterinarian as an expert witness. And no wonder: Nearly all worked for zoos, which feared for their own operations should the Endangered Species Act protections be extended to captive wild animals. But the plaintiffs lucked into Philip K. Ensley. Recently retired after 29 years at the San Diego Zoo, he agreed to review the evidence.

Ensley pored over medical documentation, regulatory records, and deposition testimony; he inspected the elephants at the Center for Elephant Conservation and on tour. He detailed his findings in a 290-page report.

“Nearly 100 percent” of the adult elephants were lame with serious foot problems or musculoskeletal disorders, he found. Their feet were misshapen, ulcerated, abscessed, and infected—no small matter for a four-ton animal forced to spend most of its life standing in place. Twelve of sixteen young elephants suffered from various foot or limb maladies. His analysis read like the shift report at a geriatric ward: “stiffness,” “peg-legged,” “lameness,” “chronic left stifle,” “sloughing toe nails,” etc.

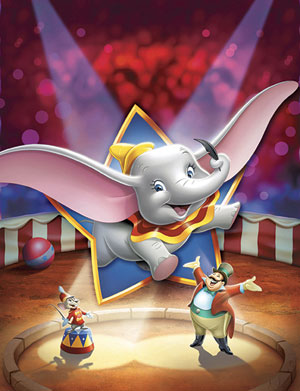

Courtesy Everett CollectionEnsley blamed the elephants’ relentless travel and performance schedule—48 weeks a year—and being forced to stand for long hours on hard surfaces for their injuries. “These are large terrestrial mammals, the largest,” he later testified in court. “I think what you’re seeing here is an abundance of conditions related to an environment that they weren’t genetically programmed for.”

Courtesy Everett CollectionEnsley blamed the elephants’ relentless travel and performance schedule—48 weeks a year—and being forced to stand for long hours on hard surfaces for their injuries. “These are large terrestrial mammals, the largest,” he later testified in court. “I think what you’re seeing here is an abundance of conditions related to an environment that they weren’t genetically programmed for.”

The Blue and Red units crisscross the country in trains of 50 cars or more, each covering 16,000 miles annually to perform in 30-plus cities. The company boasts that the animal cars are specially designed with fresh water supplies, fans, misters, and heaters, and it asserts that rest stops are built into the travel schedule to allow the animals to disembark for fresh air and exercise.

Yet Meyer’s staff found transportation orders for 600 trips from 2000 through 2008—and just 14 included rest stops. Michelle Sinnott, a young paralegal who postponed law school to work on the case, typed the data into a spreadsheet. Her calculations revealed that the elephants traveled 26 hours straight on average. Some legs extended beyond 70 hours without a break. The longest stretch: 100 hours on a 1,830-mile journey from Lexington, Kentucky, to Tucson, Arizona.

Up to five elephants are crammed in each boxcar. The average elephant produces approximately 15 gallons of urine and 200-plus pounds of solid waste in a 24-hour period. Former circus workers described the unbearable stench when they opened the cars for water stops—during which they typically replenished supplies without letting the animals out.

Feld Entertainment’s medical charts made virtually no mention of bullhook injuries. But Ensley found repeated references to scars on the animals’ left sides where handlers traditionally stand and at cue points—ears, jaws, anuses, and other sensitive spots that handlers prod to get the animals’ attention. He also found evidence elsewhere in the discovery materials.

“After this morning’s baths, at least four of the elephants came in with multiple abrasions and lacerations from the hooks,” a new veterinary technician wrote in 2004 to chief vet Lindsay. “The lacerations were very visible and I had questions at the open house from two members of the public about where they were from.”

Another Ringling animal behaviorist told a supervisor in 2005 that she’d been banned from the elephant barn after complaining about an elephant hooked so severely that it was “dripping blood all over the arena floor during the show.” She added that she saw the Blue Unit’s elephant superintendent, Troy Metzler, “hitting Angelica three to five times…and then using a hand electric prod within public view” during a train unloading in Phoenix. When Meyer deposed Metzler, he admitted to “bopping” elephants if they didn’t obey him. He said he did not believe even a forceful strike could hurt an elephant. “They are big tough animals,” he observed.

Another Blue Unit handler said he saw three to four puncture wounds a month from bullhooks, but they were considered too inconsequential to record in the medical files. When Ensley inspected the elephants with famous elephant biologist Joyce Poole and two other experts hired by the plaintiffs, they found “extensive evidence of scarring from bullhook use”—including scar tissue on Karen’s jaw where a Ringling video had shown a handler embedding a bullhook so deep that he had trouble removing it.

Ensley also found the documentation of rampant tuberculosis that the USDA had sought unsuccessfully for years. In 2000, an agency investigator had been assigned to get to the bottom of allegations that Feld Entertainment was hiding the full extent of TB infections, which can be transmitted to humans as well as other pachyderms. But company attorneys refused to turn over the medical records, and, in an internal memo, the investigator complained that Vail’s office did not back her up. (Vail does not recall this.) The discovery materials showed that as of 2008, 19 animals had been diagnosed with the disease. At least three more were discovered to have the disease when autopsied. That’s more than a third of Ringling’s population.

Faced with such damning evidence, at the March 2009 trial the company shifted its strategy from denying the practices to putting them in the best possible light.

Ted Friend, a professor of animal sciences at Texas A&M University, took the stand for the defense. He testified that the elephants likely enjoyed the train rides, because the long hauls satisfied their “nomadic” urge to roam—a theory Friend said he based on a USDA-funded study that he had conducted for the Journal of the Elephant Manager’s Association. Under cross-examination, he conceded that the study had not been peer-reviewed, and that Feld Entertainment was paying him $500 an hour to testify—$100 more than his usual hourly fee and 10 times Ensley’s rate.

Nevertheless, defense attorney John Simpson, a tall, mustachioed ex-Marine, took up the argument. “They know that when they get on that railcar that they’re going to a new place,” he told Judge Sullivan. “It stimulates them. The whole concept stimulates them.”

“But chains are put on their legs,” the judge said.

“That goes with the territory. It’s like getting in your car,” Simpson said. “It’s time to go. Put your seat belt on. It’s no different than that.”

“The average person doesn’t have to sit in their feces, though.”

When Jacobson, now the Center for Elephant Conservation’s director, took the stand, he conceded that Ringling’s baby elephants are hit with bullhooks to train them to follow commands. Sullivan twice pressed him to say whether he considered the training practices to be “humane.” Jacobson described them as “better” than they used to be, but under cross-examination he admitted that he conducts the earliest training sessions with baby elephants behind closed doors and never on videotape.

“Why don’t you think—what is it about the training that [the public] wouldn’t understand?” Judge Sullivan interjected.

“Because everything is kind of Born Free based. Everything has to be free and warm and fuzzy and, you know, we handle elephants and then, you know, they handle thousands of them in Asia, and they tie them up and they have bullhooks, you know, but in the modern world it’s just more difficult to explain, Your Honor. It is.”

When CEO Kenneth Feld took the stand, he finally admitted that his trainers and handlers hit elephants with bullhooks as a routine method of control and discipline.

“And you have seen Ringling Bros. employees strike elephants with bullhooks, haven’t you?” Meyer asked him.

“Strike, hit, touch, tap, yes. Whatever the terminology is you’d like to use, yes,” he said.

Feld also acknowledged that employees hooked elephants with the ankuses, whipped, and even shocked them on occasion, but he added that he did not believe any of those practices constituted abuse. And then he got to the bottom line: Without bullhooks and chains, Feld told the judge, the circus couldn’t have elephants. And he had no intention of letting that happen.

“I mean, the symbol of The Greatest Show on Earth is the elephant,” Feld said, “and that’s what we’ve been known for throughout the world for more than 100 years.”

The remarks might have resonated with Sullivan, who questioned whether a single judge should decide how elephants should be handled.

The summer came and went without a decision. PETA released another undercover video of Ringling workers repeatedly striking elephants as they lined up wearing pink “The Greatest Show on Earth” headdresses. (“Fuck you, fat ass,” one says as he delivers several unprovoked blows.)

On December 30, 2009, Sullivan issued a 57-page opinion that made no mention of the evidence against Feld Entertainment or the torrent of testimony about elephant misery that had rolled through his courtroom. Instead he took singular aim at Rider, the whistleblower. Adopting the defense’s argument, he wrote that payments Rider received from animal groups to talk to the press about Ringling proved his motives were mercenary—even though the arrangement was modest ($190,000 over 10 years) and had been disclosed to the judge, who had raised no objections. Sullivan cited a photo the defense had produced of Rider holding a bullhook (Rider said he never used it) as further evidence the former barn man didn’t really care about the elephants and thus had no standing to sue on their behalf. He ruled the animal welfare groups weren’t harmed by Ringling’s treatment of its elephants and so didn’t have standing either. “Because the Court concludes that plaintiffs lack standing, the Court does not—and indeed cannot—reach the merits of plaintiffs’ allegations,” he wrote.

That March, just ahead of the cherry blossoms, the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus marched its prized herd of elephants around Capitol Hill, an annual rite announcing the arrival of its traveling show. But this time, instead of swinging east of the Capitol, as it had in the past, the procession veered west, heading straight into the dark canyon of buildings that make up the federal courts complex. Lead defense attorney Simpson, in a brown leather bomber jacket, strode alongside the animals as they passed directly under Judge Sullivan’s window.

The plaintiffs appealed, but on October 28, 2011, a three-judge panel of the US Court of Appeals in Washington, DC, upheld Judge Sullivan’s decision on standing. Feld Entertainment is pursuing sanctions and more than $19 million in legal expenses, alleging they and their lawyers conspired to pursue a fraudulent case against the circus. Meanwhile, the elephants’ fate is back in the hands of the USDA. In 2010, PETA asked for a status report on the USDA’s six-year-old investigations into Angelica, Riccardo, and a young lion that died in a train trip across the desert. The agency responded that the statute of limitations had run out. So last March, PETA petitioned the agency to reopen the cases and revoke Feld Entertainment’s exhibitor’s license. The organization also took the trial evidence to the Federal Trade Commission, asking that Feld Entertainment be barred from claiming its elephants are trained with positive reinforcement. Both matters are pending, as are investigations into subsequent videos and reports of abuse. Vail said he considered the “fuck you, fat ass” incident a clear-cut violation but added that he thought TB would prove to be a much bigger problem for Feld Entertainment. New guidelines for TB are under consideration that would utilize a faster test to identify infected elephants—potentially complicating logistics for touring circuses, which also could face the prospect of state health officials turning them away. “That’s probably going to be the downfall of Feld’s elephants,” Vail predicted.

One final note: During the trial, Feld Entertainment called Kari and Gary Johnson as their leading experts in industry standards for elephant care and management. The Johnsons are the proprietors of Have Trunk Will Travel, an elephant rental company in Southern California that supplies elephants for rides at fairs, weddings, commercials, and movies. The USDA also has tapped them to conduct agency staff trainings.

Recently one of their elephants, Tai, starred as Rosie in Water for Elephants, a movie that depicts circus animal abuse. The Johnsons claimed that in real life Tai had been trained humanely. But in May, Animal Defenders International released a 10-minute video compilation from 2005 of the Johnsons and other trainers repeatedly striking and shocking elephants. At one point, the video captures Tai’s cries as a trainer shocks her with an electric prod to get her to perform a headstand.

In a written statement, the Johnsons said the video was heavily edited, that none of it was taken during training for the movie, and that “you can make something look like anything to suit your purposes.” But they don’t deny that the images show the methods they use to train elephants.

A spokesman for the USDA said an inspector was dispatched to “fully look into the matter” and “turned up no evidence of abuse.”

Front page image: Jonathan Bruck/Flickr