<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/36266791@N00/2986303105/" target="_blank">Andreas Schaefer</a>/Flickr

If you ever have the chance to visit Kuantan, Malaysia, take it! The people are friendly, the beaches uncrowded, and the sea breezes refreshing. And don’t even get me started on the food: At one café on a fishing dock I had a big bowl of soup with freshly made rice noodles and fish just caught from the South China Sea, for all of 4 ringgit (about $1.30). One fisherman I talked to boasted that the seafood alone makes a trip to his city worthwhile. “But,” he warned, “you’d better come soon.”

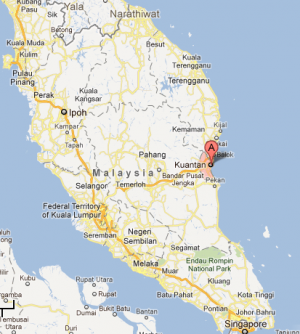

He was referring to how his home might change with the imminent completion of the largest rare-earth refinery in the world. If all goes according to plan, an Australian mining company called Lynas will begin shipping ore this summer from the Mt. Weld mine in western Australia to its refinery here, just a few kilometers from the heart of town. The refinery will produce rare-earth elements that are key to manufacturing all kinds of cutting-edge technology—from smartphones and laptops to wind turbines and hybrid-car motors to defense technology, such as navigation systems in smart bombs. Lynas says the new refinery will be able to supply a fifth of the world’s rare earths.

Image by Google Maps

Image by Google Maps

But rare-earth refining is a messy business—and some people suspect that Lynas is choosing to do it in Malaysia in order to sidestep more stringent environmental regulations in Australia. The process requires large quantities of harsh acids, and the waste it produces includes an array of unsavory substances, including heavy metals and the radioactive elements thorium and uranium. An engineer who worked on the new refinery told me in an interview that he observed several potentially dangerous design flaws in the construction before his involvement in the project ended. Similar concerns have been reported in the New York Times. All this is especially disconcerting since Lynas plans to discharge waste water into the mouth of the Balok River, home to a thriving mangrove ecosystem and fish that are a mainstay of the local economy. The company also says it plans to recycle solid waste from the refinery into building material to sell.

Lynas says it will conduct its disposal safely; it claims it will treat the wastewater and process the solid waste so that neither can make people sick or damage the environment. The company also says it will keep workers’ exposure to radiation low. Yet in a report (PDF) on the plant from last June, the International Atomic Energy Agency made 11 recommendations for conditions that the company must meet before the plant is allowed to operate—and so far Lynas has not shown clearly how it will meet 5 of those, including where it will locate a permanent home for the toxic and radioactive parts of its waste.

Given all this, and the fact that Malaysia has already had one bad experience with a rare-earth refinery (the former site of which I investigated recently), many people in Kuantan are worried about the future—and less than thrilled that their government has promised Lynas 12 years free of taxes.

I’d heard that some officials in the state of Pahang (where Kuantan is located) had been lauding the refinery’s economic benefits. I wondered why, so I called up the Pahang government office and snagged a meeting with a senior spokesman, who agreed to speak with me only if I didn’t publish his name. I asked him what local people would get out of having the plant nearby. “A lot, a lot,” he said. He admitted that Lynas’ employment offerings would amount to only about 350 jobs. “But because Lynas is here, other companies will come.”

“Which ones?”

“Siemens,” he said. I asked whether the German conglomerate had made a formal commitment. He conceded that it hadn’t.

“So have any other companies officially said they would come?”

“Thus far, no other commitments yet.”

I also asked him whether he was worried about the plant’s potential chilling effect on tourism, which is a major part of the local economy. He brushed that aside. “Fears created by the opposition have influenced a very tiny segment of the people, especially among the Chinese,” he said. (There are three main ethnic groups in Malaysia: Malays, Chinese, and Indians. Malays are in the majority, and make up most of the current government.) “The Malays are not worried, because we have been telling them that this project is safe, so why would they fear?”

But in Kuantan I found that many Malays I met did not share the government spokesman’s confidence in Lynas. With the help of Lee Tan—a multilingual environmental consultant and Kuantan native who now lives an Australia but hasn’t forgotten a single crevice of her hometown—I chatted with food-stand owners, fishermen, and many others.

Our first stop was a roadside fish stand in the village of Sungai Karang, where the owner, 31-year-old Jamil Jusuf, was making his specialty: fish fingers (think fish sticks, but about a million times tastier) and spicy fish meal wrapped tightly in leaves and grilled over an open flame.

Jusuf told us that he first heard about the refinery from customers. “They told me that the waste will go right where I get my fish from,” he said. He suspects that some tourists mistakenly believe that the plant is already up and running; he says he’s gotten a lot of Lynas-related questions from them. This year, his sales are 3,000 ringgit (about $1,000) short of where they are normally.

Jusuf told us that he first heard about the refinery from customers. “They told me that the waste will go right where I get my fish from,” he said. He suspects that some tourists mistakenly believe that the plant is already up and running; he says he’s gotten a lot of Lynas-related questions from them. This year, his sales are 3,000 ringgit (about $1,000) short of where they are normally.

We needed some dessert, so we drove down a winding road to another little stand. This one sold chewy little cakes made of coconut, duck eggs, and rice flour—the texture of Japanese mochi. We met a customer on a motor bike, whose two little kids sported Angry Birds PJs:

Motor Bike Dad said he was worried about radiation that he’d heard the plant would produce, but was afraid to talk about it openly. (This was a theme throughout my interviews. The fear was understandable, since the government jailed people who protested Malaysia’s last rare-earth refinery.)

Motor Bike Dad said he was worried about radiation that he’d heard the plant would produce, but was afraid to talk about it openly. (This was a theme throughout my interviews. The fear was understandable, since the government jailed people who protested Malaysia’s last rare-earth refinery.)

Fishing boats on the Baluk River, just outside of Kuantan and minutes from the Lynas refinery siteNext we decided to hang out at a fishing dock by the sea for a while, where we met the elderly owner of a fleet of 27 fishing boats, who didn’t want to be photographed. When we asked him about Lynas, he shrugged. He had heard about the waste, “but the government doesn’t care, as long as there’s money.” (Then he launched into a long Mandarin monologue to Lee, the amazing upshot of which was: Yeah, that rare-earth plant is going to suck. But you know what’s really bad? Pirates. My boats are regularly captured by pirates near the border of Indonesia. Then I have to pay an arm and a leg to get them back. It’s annoying, since the whole time I can see where the boat is on the internet. Yes! Really!)

Fishing boats on the Baluk River, just outside of Kuantan and minutes from the Lynas refinery siteNext we decided to hang out at a fishing dock by the sea for a while, where we met the elderly owner of a fleet of 27 fishing boats, who didn’t want to be photographed. When we asked him about Lynas, he shrugged. He had heard about the waste, “but the government doesn’t care, as long as there’s money.” (Then he launched into a long Mandarin monologue to Lee, the amazing upshot of which was: Yeah, that rare-earth plant is going to suck. But you know what’s really bad? Pirates. My boats are regularly captured by pirates near the border of Indonesia. Then I have to pay an arm and a leg to get them back. It’s annoying, since the whole time I can see where the boat is on the internet. Yes! Really!)

We headed over to another fishing dock, this one on the Balok river. We found a few guys hanging around. “I’m not sure whether to be worried about Lynas yet,” one said in Malay. “Most people around here have very limited education, so we don’t understand these technical issues.” A moment later he produced a beat-up booklet bearing the Lynas logo. The title was in Malay: BUKU INFORMASI LYNAS (Lynas information booklet). “Lynas has come here many times to hand out pamphlets,” he said. Later, Lee translated the pamphlet for me. “The Lynas plant will not be dangerous to the public, the surrounding area, or its workers,” declared one bolded heading.

Curious, I decided to look into some of the booklet’s claims. Most of the 12 experts I spoke to—engineers, mining consultants, and environmental scientists—agreed that Lynas’ plan to scrub all the toxic elements out of its waste is technically possible. But not one of them had seen sufficient explanation—from either Lynas or the Malaysian government—of exactly how it would do this. Others, including Kuantan’s parliamentary representative Fuziah Salleh, have pointed out that Lynas has only been required to submit a preliminary environmental impact assessment, which doesn’t address in detail the plant’s potential effects on the mangrove ecosystem and marine life.

I had trouble nailing down Lynas’ specific plans, too. When I submitted questions to Lynas about whether it had plans for a permanent waste-storage facility, I received no response. I also asked how the plant would treat its liquids for release into the river and solids for recycling into construction materials. Lynas spokesman Alan Jury declined to provide specific answers and instead referred me to the IAEA’s review of the plant, which only addresses radiation—but not the acids, heavy metals, and other substances that will be present in the waste. “The IAEA found Lynas to be fully compliant and meeting international standards,” Jury noted.

“I don’t see the waste as impossible to manage, but you can’t do it in secret, and you can’t do it without good numbers,” said Gavin Mudd, a professor of civil engineering at Australia’s Monash University. “If Lynas is so confident in its methods, then it should have no problem being transparent.”

After returning to Kuala Lumpur from tranquil Kuantan, the capital city seemed even more crowded, noisy, and sweltering than I remembered it. From my hotel room, I could hear tourists belting out Whitney Houston hits at a neighboring karaoke bar. I headed out for a walk. Over a snack at a food stall (which I thought was going to be ice cream but somehow ended up being a dark brown herbal jelly) I kept thinking about the Lynas pamphlet the fisherman had shown me—could the company really assure the Kuantan people that the refinery was safe? And could their government?

I tracked down an engineer who worked on the Kuantan plant. (He requested that I not reveal his name, employer, or other identifying details about his work.) Early on in the construction process, the engineer said, his team noticed that the moisture content in the concrete of 22 tanks—which would hold acids, rare-earth elements, and the radioactive waste—was too high for the lining to be applied. When the engineers notified Lynas of the problem, it dispatched a team to deal with the issue, which proceeded to set about drying the concrete with fans and blowtorches. “After a few weeks of this, we noticed that the moisture would reduce, then go back up again,” the engineer said. So his team conducted an inspection and found that there were no moisture barriers under the tanks—the moisture from the ground was seeping in. Upon further inspection, his team also found cracks in the tank that ran from the floor to the top of the wall. It also discovered “honeycombing,” or areas where the concrete had not been properly compacted. These were problems, he said, that ultimately lead a Dutch contractor, AkzoNobel, to pull out of the project. (According to a New York Times report, Lynas denied that AkzoNobel’s withdrawal was related to the design problems.)

“My personal opinion is that the plant can operate safely,” the engineer noted, “providing that it’s effectively engineered.”

Lynas denies the allegations of design flaws; spokesman Jury wrote in an email that the company’s change of contractors was a “commercial decision” and assured me that the new contractor, Trepax Thailand, “is applying the vinylester lining to meet the international industry standard.”

Raja Aziz Image by AELB MalaysiaI still wondered, though, whether the Malaysian government had made sure the tanks had been fixed, so I attended a press conference with Raja Dato Abdul Aziz bin Raja Adnan, the head of Malaysia’s Atomic Energy Licensing Board, the body that will decide whether Lynas will get a license to operate. I asked Aziz, who never seemed to break a sweat or stop grinning, even as a room full of reporters pelted him with pointed questions, whether the board had looked into the plant flaws. Aziz responded that the plant had been inspected by a registered engineer. When I asked for the engineer’s name, Aziz declined to give it. Why wasn’t the report available to the public? I asked. “Because it’s Lynas’ document,” Aziz said. “But if it’s Lynas’ document, then Lynas was the one who looked into the allegations made in the New York Times?” I asked. He demurred, so I asked again who inspected the plant.

Raja Aziz Image by AELB MalaysiaI still wondered, though, whether the Malaysian government had made sure the tanks had been fixed, so I attended a press conference with Raja Dato Abdul Aziz bin Raja Adnan, the head of Malaysia’s Atomic Energy Licensing Board, the body that will decide whether Lynas will get a license to operate. I asked Aziz, who never seemed to break a sweat or stop grinning, even as a room full of reporters pelted him with pointed questions, whether the board had looked into the plant flaws. Aziz responded that the plant had been inspected by a registered engineer. When I asked for the engineer’s name, Aziz declined to give it. Why wasn’t the report available to the public? I asked. “Because it’s Lynas’ document,” Aziz said. “But if it’s Lynas’ document, then Lynas was the one who looked into the allegations made in the New York Times?” I asked. He demurred, so I asked again who inspected the plant.

“I looked into the allegations,” he said.

“You personally looked into them?”

“We looked into them.”

“So then why can’t you tell me the name of the engineer who inspected the building for the safety flaws?”

“That’s for you to find out.”

Right. When I later asked Jury about the alleged inspection report, he said he didn’t have it and referred me back to AELB, the Malaysian Department of Environment, and the International Atomic Energy Agency.

On the day that I left Malaysia, a group of Kuantan residents filed suit against the AELB, alleging that the body had a conflict of interest in a deal it made whereby it would receive 0.05 percent of the revenue generated from the Lynas plant. When the news site Malaysian Insider asked Aziz about the suit, he responded, “I don’t know anything about it. Ask MITI [the Ministry of International Trade And Industry].”

Over the course of my trip, it had become abundantly clear to me that all this obfuscation had not inspired confidence in the local population. In Kuantan especially, there was much eye-rolling about the secrecy surrounding the refinery, and the frustration was palpable: Many said they didn’t even see the point in protesting when they knew the government was going to do whatever it wanted anyway.

Malaysians also know that rare earths are in high demand. And that puts them in a tough spot. As one reader wrote (in slightly broken English) in the comments section of my last dispatch, “Malaysians are not against new, green technology that rare earth material supports. Just asked for these technology to be clean from cradle to grave, particularly when you’re processing it in another’s backyard.”

You can bet that Malaysians—and perhaps the rest of us whose smartphones, cars, wind turbines, and missiles rely on rare earths—will be watching closely to see how this situation plays out. For now, though, I’ll leave you with one last anecdote: On my last night in Kuantan, I talked to a 62-year-old man named Chow Kok Chew who had moved to Kuantan 30 years ago—from the town of Bukit Merah to get away from the former rare-earth refinery there. He said he was dismayed when he found out about the plans for a new refinery in Kuantan. Since then, Chew has been spending most of his spare time reading up about the plant—and encouraging his friends to do the same. “If I don’t do something,” he said, “I’m worried that my grandson will say, ‘Grandfather, the first time you kept quiet. The second time you kept quiet, too. Why?'”

A public beach just a short distance away from where Lynas’ refinery will release its wastewater

A public beach just a short distance away from where Lynas’ refinery will release its wastewater

Reporting for this story was partially funded by a grant from the Society of Environmental Journalists.