A man travels between coconut groves near Ben Tre province's new dam.Kate Sheppard

There wasn’t much time to think when Typhoon Durian hit Pham Van The’s farm. Pham and his wife, Duong Thi Hai, were working in their melon fields when the storm struck, pushing a wall of water toward them. “I couldn’t grab anything,” Pham says. “I just grabbed my wife’s hand and said, ‘You have to follow me! Don’t go anywhere else, or we’ll die.'” They ran inland. Neighbors with boats pulled them to safety.

In the last few years, Pham has seen more storms and high tides than ever before. His farm sits where a broad branch of the Mekong River joins the South China Sea, in a delta highly vulnerable to sea level rise.

I meet him on a humid April day after taking a wooden boat out to this part of Ben Tre province with Nguyen Thanh Lap, a nature reserve director working with Vietnam’s National Target Program to Respond to Climate Change. Storms like Typhoon Durian may already be growing fiercer and more frequent here, and storm surges are expected to grow in years to come. Part of Nguyen’s job is to persuade coastal farmers to plant mangrove trees, whose wide base of spindly roots holds sediment and blocks storm surges. But it’s a tough sell. “These people make money on their land,” Nguyen says. Even the narrow strip that the mangroves require would make a difference in a farmer’s income.

When we arrive, Pham and Duong are resting in the shade of a thatched shelter. Pham, 61, is short and bronzed by the sun. He laughs easily, even when telling stories about narrowly escaping raging waters. He rolls a cigarette as we talk, the salty breeze cutting the midday sun. His melon fields extend behind us, the vines creeping out from long, neat rows in the sandy soil.

Pham used to have a little more than one acre of melon fields—land the socialist government gave him 25 years ago. But then the water started slowly reclaiming the sand. “The sea was swallowing it up,” he tells me through a translator. Now he estimates that he has maybe three-quarters of an acre left. He and Duong have built a three-foot barrier with sand, fronds, and beach debris, but the makeshift seawall doesn’t look like it would stand up to a typhoon.

Vietnam has 2,025 miles of coastline exposed to rising seas. Eighteen million of its 88 million people live in the Mekong delta, 1.4 million in Ben Tre—a big island cut off from the mainland by the Mekong. Under worst-case sea level projections, half of Ben Tre would be under water by 2100.

From its ostentatious People’s Committee office buildings, the Communist Party controls everything at the provincial and local levels, so it’s easy for the government to declare a national policy; what’s not so easy is finding the resources to implement it. I traveled here because, while Vietnam faces a flooding threat similar to, say, coastal Virginia, its main problem is pretty much the opposite of US climate politics: plenty of will to deal with the issue, but virtually zero money. Saving all of Ben Tre, let alone all of Vietnam, from the rising seas would require billions; so far, the Target Program has a $94 million budget for five years, 40 percent of it from the Danish government. “I hope you will write a good article and help attract investors and sponsors to Ben Tre,” one of the program’s leaders implores me.

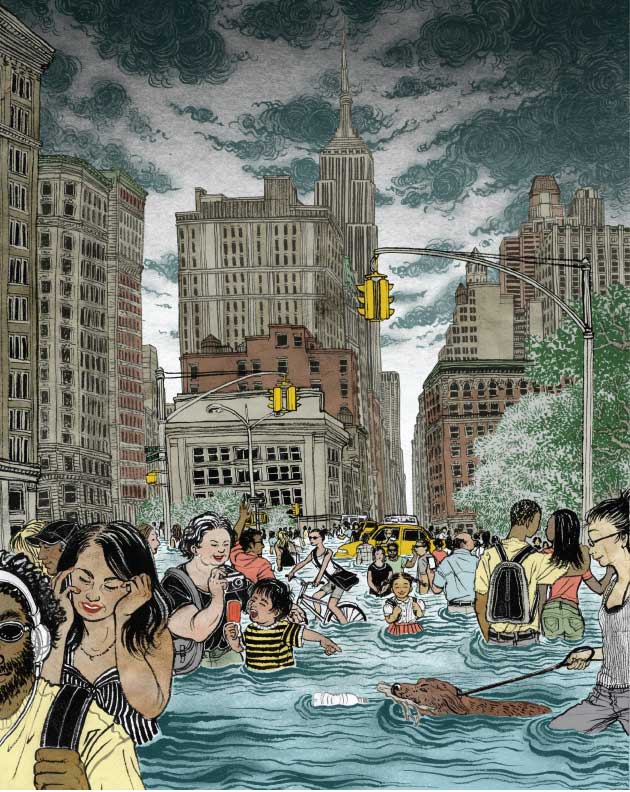

What I see on the ground, as a result, is somewhat haphazard—a long wish list from local officials and a few small projects in various stages of completion. One is an earthen dam that closes off a branch of the Mekong to keep salt water from the South China Sea out of the freshwater that farmers and households need. The dirt levee works, but at $200,000 it was expensive by Vietnamese standards. Thousands of other farmers whose freshwater is at risk of turning brackish won’t see a project like this anytime soon. Same with Nguyen’s mangrove forestation project: He has started a nursery with 5,000 seedlings thanks to $200,000 from the local government and a small grant from the World Wildlife Fund. He wants to expand to 1 million seedlings, but that will require more money.

The government does provide farmers some compensation for planting and caring for the trees, but only about $155 per acre, plus a small annual commission for maintenance, far less than they would make on melons; Pham brings in about $1,400 a year from farming his three-quarter-acre plot. “It’s hard to convince them to give up this short vision for a long one,” says Nguyen as we walk down the beach.

Pham, for his part, tells us he’s on board with planting trees, but the 15 other neighboring farmers also need to agree before the project can go forward. In the meantime, Pham will keep fighting back the tides himself. “I’m going to hold up against it if God is kind,” he says. “If he’s harsh, I will have to retreat.”