<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-178208153/stock-photo-asian-boy-wearing-mouth-mask-against-air-pollution-beijing.html?src=dt_last_search-3">Hung Chung Chih</a>/Shutterstock

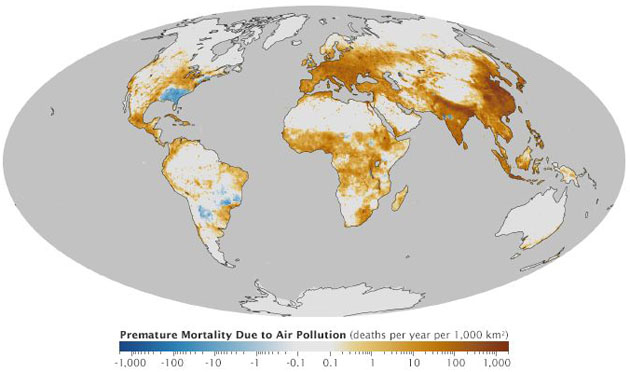

Nations around the world could save more than 2 million lives every year by cleaning up their air, a new study has found. Researchers identified major potential public-health gains not only in the most polluted places like China, but also in the United States and Europe.

If China and India alone met pollution targets set by the World Health Organization, they could avoid about 1.4 million premature deaths annually, according to a study published Tuesday in Environmental Science & Technology. (For comparison, that would be nearly as many lives saved as if we cured everyone in the world who dies from an HIV-related illness every year.)

To do that, these countries would need to meet the WHO’s guidelines for a type of pollutant known as fine particles, which were linked to about 3.2 million premature deaths globally in 2010, the researchers found. Fine particles, which are about 28 times finer than a strand of human hair, enter the lungs and travel into the bloodstream, wreaking havoc on the body: Exposure to the particles—which can come from fires, coal-fired power plants, cars and trucks, and agricultural and industrial emissions—have been linked with increased risk of heart attack, stroke, and other cardiovascular diseases, as well as respiratory illnesses and cancers.

Most people around the world live in polluted places where their annual exposure to fine particles far exceeds the WHO’s guideline of 10 micrograms per cubic meter of air, the study says, and in some parts of China and India, people may be exposed to 10 times that amount.

Even in less polluted countries, air pollution has taken a major toll. “We were surprised to find the importance of cleaning air not just in the dirtiest parts of the world—which we expected to find—but also in cleaner environments like the U.S., Canada and Europe,” Julian Marshall, an associate professor at the University of Minnesota and a co-author of the study, said in a statement. Indeed, if these relatively clean regions met WHO guidelines, reducing annual exposure to fine particles by between one and four micrograms per cubic meter of air, they could avoid hundreds of thousands of premature deaths per year, the study found.

In the United States, the Environmental Protection Agency also has guidelines for fine particle pollution, but they aren’t quite as strict as the WHO guidelines. “If we only meet U.S. Environmental Protection Agency standards, we aren’t fully addressing the problem,” said Marshall.