RJ Sangosti/Denver Post via Zuma

This story originally appeared in The New Republic and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

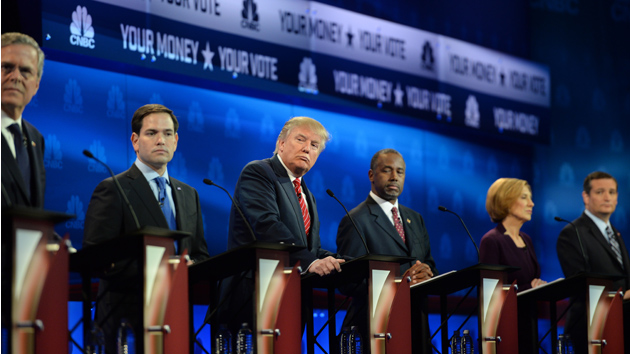

On stage at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in mid-September, two-plus hours into the second GOP presidential debate, the candidates were shifting under the glare of the klieg lights as moderator Jake Tapper began grilling Senator Marco Rubio about one of the Republicans’ least favorite topics: climate change. When evidence mounted in the 1980s that the ozone layer was shrinking, the CNN anchor noted, “Ronald Reagan urged skeptics in industry to come up with a plan … and his approach worked.” So why not “approach climate change the Reagan way?”

It was fitting that Rubio, who is working harder than any candidate to present himself as the party’s face of the future, was the one who had to field the question. Forward-thinking people, as the senator from Florida knows very well, do not deny science. But at the same time, as Rubio also knows, Republicans in search of conservative votes have long felt compelled to do just that.

So he glared down at Tapper and attempted a dodge, firing back: “Because we’re not going to destroy our economy the way the left-wing government that we are under now wants to do.” Rubio, clearly well-drilled to answer the question, went on: “We are not going to make America a harder place to create jobs in order to pursue policies that will do absolutely nothing, nothing to change our climate, to change our weather.”

And why are these climate policies doomed to fail? Because, Rubio said, “America is not a planet.” What he meant is that America acting alone is futile without action from other countries, particularly China. And China, of course, would never act. “They’re drilling a hole and digging anywhere in the world that they can get a hold of,” Rubio opined. Chris Christie, Tapper’s next target, eagerly agreed, dismissing the idea that we can fix the problem “by ourselves” as a “wild left-wing idea.” Other GOP candidates had previously said much the same in other settings. “Look at China, they’re doing nothing,” Donald Trump proclaimed in September on Morning Joe, adding his well-considered scientific assessment that America’s efforts are doomed because “it’s a big planet.”

As it happens, a few months earlier, China had announced an ambitious new plan to limit its carbon emissions—a development that had been widely covered by major news outlets across the country. But among those on the debate stage, it was an article of faith this announcement from China couldn’t possibly have any meaning—if, that is, it had really happened at all.

Other Republican candidates have taken a slightly different tack on climate: Yes, conservatives should accept the science, but they should be wary of drawing hard conclusions from it. Jeb Bush, for one, admits that “the climate is changing,” and says conservatives should “embrace science”—but adds that claiming the science on climate is “decided” is “really arrogant.”

None of these rhetorical acrobatics will surprise anyone who has paid the slightest attention to the Republican Party’s approach to one of the defining challenges of the twenty-first century. Faced with the inconvenient scientific consensus that the only planet in the solar system known to be fit for human habitation is getting hotter, and may soon be doing so irreversibly, the GOP—one of the two major parties that govern the world’s second-largest emitter of greenhouse gases—has for years responded by developing a complex, shifting series of denial mechanisms that preclude any serious participation in the debate over solutions.

These denial devices have become so sophisticated and all-pervasive that a whole journalistic subgenre—a species of climate cryptology—has sprung up to ponder and interpret their inner workings. Lately, the cryptologists have been detecting subtle signs of a GOP evolution on climate. While it’s long been standard for Republican candidates to question, evade, or reject climate science, GOP candidates in last year’s midterm elections began routinely responding to climate questions by throwing up their hands and repeating some variation of, “I’m not a scientist.” More recently, some GOP officials and presidential candidates have taken to acknowledging global warming while insisting that the private sector—not Big Bad Government—must solve it. It’s a step forward, if only a baby step.

But these subtly encouraging shifts have to be measured against a dispiriting assessment of just how large the stakes are right now. The Republican Party is well positioned to deal immense setbacks to the best efforts taking shape, at long last, to combat the escalating risks we face from a warming world.

In the near term, Republicans are threatening to throw a wrench into the implementation of President Obama’s recently completed Clean Power Plan (CPP), which aims to reduce carbon dioxide emissions from U.S. power plants by 32 percent by the year 2030, relative to 2005 levels. (Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has angrily vowed to stop this “bureaucratic and regulatory menace.”) By itself, this Environmental Protection Agency plan is a vastly insufficient response to the long-term carbon challenge. But it is the most ambitious step the United States has ever taken to curb carbon emissions, and it could help lay the groundwork for a global climate deal to be negotiated in Paris in December, when more than 190 participating countries are expected to commit to reductions in their greenhouse gas emissions. This agreement may, in turn, provide a foundation for more international action in the next decade.

The emerging global effort to combat climate change will hinge, in part, on whether the United States can successfully implement the CPP. If we can’t, it would complicate our ability to meet our obligations in a global accord and weaken the incentive for other countries to meet their commitments. Yet influential figures in the Republican Party are working to block the CPP on multiple fronts: They’re filing lawsuits against the EPA, applying political pressure to state officials who are poised to implement the plan, and working to sow doubts among our international partners about America’s political will to fulfill our end of an international deal. If any of those efforts pay off, it would seriously set back the emerging efforts to combat global warming. So could a new Republican president in 2017.

This has created an odd situation that was recently summed up by New York magazine’s Jonathan Chait: “The entire world is, in essence, tiptoeing gingerly around the unhinged second-largest political party in the world’s second-largest greenhouse gas emitter, in hopes of saving the world behind its back.” And indeed, there are grounds for thinking that the most hopeful scenario might be that Democrats keep the White House, and international efforts continue unfolding while (at worst) Republicans try and fail to block them, or (at best) just sit the whole thing out.

But allow me to suggest a preposterously optimistic alternative possibility. Even as Washington Republicans continue working to undermine the CPP, we might simultaneously see a surprising number of red states quietly cooperate with the EPA in implementing the plan, thereby helping to reassure the rest of the world that we are taking our obligations seriously. And meanwhile—trust me, this is not as crazy as it sounds—the seemingly unbreachable wall of Republican hostility to climate science may continue to erode. The party could grow more and more open to joining the debate over how to solve a problem many Republicans recently dismissed as an airy liberal fantasy or an elaborate scientific hoax.

In the long run, this would be great news for the country—and for the planet. But if Republicans do evolve on climate, it won’t happen tomorrow. How much damage can the party do along the way? Will its hostility to Obama and his climate policies render our political system too paralyzed to meet this challenge before it’s too late?

This fall, we got a revealing glimpse into just how deep Republicans’ climate skepticism runs. In advance of Pope Francis’s visit to the United States, a resolution circulated among House Republicans that acknowledged the scientific evidence of a changing climate and the threat it poses to human survival. The resolution called for no concrete solutions, only saying that Congress should commit to studying and addressing the issue at some indeterminate point in the future. Yet just 11 of 247 House Republicans were willing to sign it—a measly 4.5 percent of the GOP caucus.

What’s particularly dispiriting about this state of affairs is that the environment used to be a bipartisan cause. The 1970 Clean Air Act, which is now providing the legal foundation for Obama’s CPP, passed by overwhelming bipartisan majorities, as did the crucial 1990 amendments expanding that law to deal with acid rain and other challenges.

It’s hard to say when, precisely, Republican lawmakers turned en masse against climate action. But one clear marker of it came soon after Obama took office. The president had promised that his election would mark the moment when “the rise of the oceans began to slow and our planet began to heal.” Republicans widely mocked this phrase as evidence of an Obama messiah complex rather than a vow to address an urgent global threat. Obama’s GOP opponent, John McCain, lampooned it in an ad in which the voiceover intoned: “It shall be known that in 2008, the world shall be blessed. They will call him: The One.”

Soon after Obama took office in 2009, the mockery turned serious: 168 House Republicans voted down the country’s first major legislative effort to meet the global challenge—Obama’s cap-and-trade bill, which had been based on GOP-friendly market reforms once favored by conservatives like McCain. Only eight backed it. (Opponents killed it in the Senate, where it never got a vote.)

After Republicans took back the House in 2010, climate vanished entirely from the congressional agenda. Since then, the Republican approach to the issue has been characterized mostly by sheer, blank-faced indifference. Douglas Heye, a senior adviser inside the House GOP leadership’s inner sanctum from 2012 to 2014, recently told me he heard not one single discussion of the issue among GOP leaders or lawmakers the entire time he was there. “I don’t recall any conversations about it one way or the other,” Heye said. Nor, he said, were the members hearing a peep about climate from their constituents.

When climate change has cropped up in Republican politics in recent years, it has often been cast as a cultural issue (albeit not one that inspires quite the passion of, say, guns or gay marriage). Derision aimed at pointy-headed Al Gore’s climate advocacy had long been a mainstay on the right. In the Obama era, conservative voters have come to associate any discussion of climate change with being talked down to—not just by the president, Heye told me, but also “by Eastern elites, whether it’s Neil deGrasse Tyson or Bill Nye or The New York Times editorial page.”

Meanwhile, the two parties have grown more polarized on environmental issues. Conservative Democrats who had been hostile to climate solutions have seen their ranks greatly thinned, leaving behind a Democratic Party more unified around action. On the right, public opinion researchers have found that hostility to the science has hardened among conservative voters. This hems in GOP lawmakers who might privately accept the science. It’s often argued that the GOP’s climate intransigence is driven by big donors such as major energy companies or the billionaire Koch brothers. But House Republicans may be more motivated by fear of the conservative base in their districts—and by potential right-wing primary challengers—who see any sign of openness to climate science as capitulation to Obama and coastal elites.

Bob Inglis can testify to that. A conservative Republican from South Carolina who served six terms beginning in 1993, Inglis was ousted in a 2010 primary challenge by Tea Party stalwart Trey Gowdy, partly (but not exclusively) because he embraced climate science. Inglis’s son had persuaded him to take global warming seriously, and he’d dared to talk about it on the campaign trail. Inglis’s opponents painted him as an apostate, and he found himself being booed with regularity by conservatives in the district. “It’s the most enduring heresy I committed,” Inglis told me, laughing.

After leaving Washington, Inglis took up the issue as a calling, founding a group called RepublicEn that aims to convince the GOP to accept the science. But he has run into the same problem again and again: Lawmakers are mortally afraid to go there. “The science is clear,” Inglis said. “But the most important people in the party on this issue are the activists within the local parties. What they lack in substance they make up for in volume. They create fear in the heart of the average member of Congress.” And no fear speaks to politicians quite like the fear of losing their jobs.After the failure of cap and trade and faced with implacable Republican opposition to legislative climate solutions, Obama began to look for ways to move forward through executive action—a process that has culminated in the CPP. It’s hardly a shock that leading Republicans have loudly condemned it. But beyond the political noise, what can Republicans actually do to thwart the plan and stymie evolving global efforts to act? The answer is, unfortunately, a lot.

After the failure of cap and trade and faced with implacable Republican opposition to legislative climate solutions, Obama began to look for ways to move forward through executive action—a process that has culminated in the CPP. It’s hardly a shock that leading Republicans have loudly condemned it. But beyond the political noise, what can Republicans actually do to thwart the plan and stymie evolving global efforts to act? The answer is, unfortunately, a lot.

For starters, more than a dozen states, most of them red, are suing to overturn the CPP as illegal. Under the plan, the EPA will set individual carbon reduction targets for states to meet. States can come up with their own proposals to hit those targets by choosing from several options: among them, imposing a carbon tax on polluters, boosting renewable energy sources, transitioning from coal to natural gas, or implementing cap-and-trade systems. If they fail to develop a proposal—which they must submit by 2018 at the latest—the EPA will develop one for them.

The states targeting the plan in court make a complicated technical argument: Because of statutory inconsistencies rooted in conflicting amendments to the Clean Air Act passed by Congress in 1990, the EPA does not have the regulatory authority it claims. Some also argue that the CPP coerces state compliance in violation of the Tenth Amendment.

The legal battle—which is backed by a sprawling web of business groups, energy lobbyists, conservative advocacy organizations, and Republican allies in Congress who argue the plan will make energy costs skyrocket—will work its way through the system and may be decided by the Supreme Court by 2017 at the earliest. The courts could uphold the rule, or they could require changes in implementation that would slow it down. They could also throw out the CPP entirely.

Supporters of the CPP are cautiously optimistic that it will stand up to the legal challenges, arguing that it’s in keeping with decades of Clean Air Act regulation that set similar anti-pollution goals for states. “I expect that the regulation will ultimately be upheld,” said New York University professor Richard Revesz, a prominent defender of the plan. “But the worst-case scenario is that the courts say the EPA doesn’t have the authority to regulate greenhouse gases from power plants. This would seriously set back our efforts to combat climate change.”

In the meantime, prominent Republicans have spent this year hatching other efforts to derail the CPP. Senator Mitch McConnell, most notably, has publicly urged Republican governors to resist the CPP by refusing to submit their own proposals. His goal is to diminish the chances of a global climate deal by sowing doubts among other countries about whether the United States will have the political will to meet its end of the carbon reduction bargain. But this McConnell ploy, despite its almost comic levels of moustache-twiddling and diabolical scheming, is likely to fail. Observers still expect an international deal in December, and it’s unclear at best whether resistance from GOP governors would even have much of an impact on the talks in any case.

The legal challenges and political strategems could ultimately come to naught. But the most ominous threat to climate progress will remain: a Republican winning the White House in 2016 or 2020. A Republican president could try to repeal the CPP with the help of a GOP Congress, or try to undo or weaken it through executive action. Either course of action would undermine our international credibility and imperil global efforts down the road.

It’s conceivable, of course, that a Republican president might decide against wasting political capital by taking on the difficult task of rolling back the CPP when it’s already being implemented. But that would likely mean ignoring a campaign promise and risking the wrath of the right. Republican presidential candidates have already condemned the plan as “lawless” (Ted Cruz), “unconstitutional” (Bush), and potentially “catastrophic” (Rubio). The hyperbole will likely ratchet up if an international deal is reached in Paris, shining a sharper light on Obama’s climate actions among conservatives. A global deal, after all, provides a rich buffet of red meat to the base—it features energy mandates, U.S. cooperation with Euro-weenie bureaucrats, and a need for trust in China.

It’s Grade A fodder for demagoguery. “Republican voters, by and large, are skeptics on climate change, and anything that Obama does, a Republican primary voter basically hates,” GOP consultant John Feehery told me recently. “For Republican primary voters, China is a bogeyman. They will look favorably on any candidate who attacks an agreement with the Chinese that was negotiated by Obama.”

Thus, the Republican candidates—even those who aren’t climate skeptics or deniers—will remain unremittingly hostile toward Obama’s plans for domestic and international action. And if one of them lands in the White House, she or he will then be in a position to set us back years. The election forecasters tell us the chances of that are close to 50-50.

And yet, little by little, though it may be as imperceptible as the moment-to-moment melting of a polar icecap, you can see signs of a thaw in the GOP’s climate intransigence. The most significant sign: While Republican candidates and members of Congress continue to rail against the CPP, other GOP officials are already beginning to cooperate with it behind the scenes. And that cooperation could ultimately prove more important, and a stronger portent of what’s to come, than the bluster in Washington.

When it comes to climate, there are essentially two Republican parties. The first is the more nationally visible one dominated by congressional Republicans, presidential contenders, and figures throughout the conservative media entertainment complex who play to a right-wing audience. This Republican Party will likely remain hostile to the science and to most government climate solutions for years.

The second Republican Party is made up of governors, state government officials, and energy regulators in states—and this is where the thaw is taking place. Even as attorneys general in many states are suing the EPA, officials in some of the very same states are simultaneously gearing up to comply with it. Michigan’s attorney general has signaled intent to join the lawsuit, for instance, but Republican Governor Rick Snyder has announced that the state will draw up its own plan.

Several administration officials I spoke to said they have been quietly meeting with officials and regulators from a number of other red states about setting up their own plans. In these conversations, according to one senior official, there has been “near zero political posturing”; these are no-nonsense career government insiders who are “exclusively looking at this as just the next thing they have to implement.” As a result, the Obama administration is increasingly confident that even conservative states, such as Wyoming, Nevada, and Arizona, will comply. New Mexico has already said that it will, and officials in Arkansas, Georgia, North Dakota, and Utah have reportedly been considering it as well. The rationale is clear: If the CPP survives in court, these states will be better off if they develop their own plans in cooperation with local utilities and energy companies.

Former Colorado Governor Bill Ritter Jr., a Democrat who now directs the Center for the New Energy Economy at Colorado State University, has been holding talks with Western governors’ offices to concoct a way for their states to jointly comply with the CPP after the lawsuits run their course. “There are governors and attorneys general in the West who are suing to undo the Clean Power Plan, but those states have still participated in our process of convening 13 Western states,” Ritter said. “It’s a hedge strategy if the rule is upheld. If the plan survives the litigation, those states prefer drafting their own plan rather than deferring to the EPA to write it. Even with the states suing the EPA, we have had constructive discussions about how we might establish a pathway to regional implementation.”

It isn’t strictly essential that red states comply, since the feds will enforce a plan if they don’t. But it would be good news for the CPP’s prospects if some do, in part, because state officials have direct relations with utility companies, which will have to do much of the innovating required to reduce carbon emissions. Indeed, if the lawsuits fail, you might, in turn, see some electric utilities push red-state officials to set up their own plans, because they’d rather work with their partners at the state level than deal with the EPA. “The level of cooperation from the utilities will be a big factor,” said Michael Bradley, the founder of energy consulting company M.J. Bradley & Associates. “Once the litigation is over, and once the utilities realize this is the new reality, we’ll move forward.”

Which brings us to my wildly optimistic scenario for the not-so-distant future. As more red states than expected end up complying with the CPP—and send the world a signal that the United States isn’t quite so polarized on climate as the House GOP and Republican presidential candidates would suggest—Republican politicians will increasingly acknowledge the science as they’ve already begun to do. That will set them on the path toward seeking solutions.

Inglis, the former representative who now evangelizes to fellow Republicans about climate science, sees signs that it’s coming. “In the depths of the Great Recession, Republicans said they didn’t believe in climate change,” Inglis told me. “Then, in the 2014 cycle, they said, ‘I’m not a scientist,’ an agnostic position. Now we’re somewhere in the next phase. I see a trend line toward a solutions-based conversation. We’re changing the question from, ‘Do you believe in climate change?’ to ‘Can free enterprise solve climate change?’ A candidate in front of a conservative audience can answer that in the affirmative.”

You can see hints—albeit vague ones—of this change on the campaign trail. Bush rails against Obama’s climate plans as catastrophic for the economy, but he also calls for private, “game-changing innovations.” Similarly, Carly Fiorina recently argued that “the answer is innovation. And the only way to innovate is for this nation to have industry strong enough that they can innovate.”

There is a powerful incentive for Republicans to keep evolving. Remaining trapped in an anti-science posture risks sidelining them entirely from a policy argument that is inevitable, whether they like it or not. “The debate Republicans should want is over what government should do about climate change,” said Jonathan Adler, a Case Western Reserve University law professor who regularly discusses climate with GOP lawmakers. “The debate over the science is a sideshow,” he said, with the result that Republicans “are essentially conceding the policy argument.”

Having Republicans join the debate won’t miraculously pave the way to harmonious cooperation, of course. Most will remain hostile to government “mandates” like the CPP for some time to come, and will push instead for private sector fixes. They will shun government-mandated limits on carbon, advocating for a revenue-neutral carbon tax and a government role confined to incentivizing private development of low-carbon technologies and alternative energy. But simply having them more meaningfully engage the climate consensus and offer their own fixes is something Democrats and liberals should welcome. It could boost the prospects for bipartisan cooperation over time. And after Obama has moved on to private life, the culture-war cachet of climate science may also ease, leaving more room for Republican lawmakers to take a constructive approach. ?

There is every chance, of course, that this rosy scenario may prove to have been cockeyedly, absurdly, delusionally optimistic. If Hillary Clinton is elected president, for instance, she could become the next Great Satan of environmental overreach—leading many Republicans to sit out the debate into the next decade, when we’ll be face to face with more enormously consequential decisions. But hey, no worries: If worst comes to worst, maybe the world can still find a way to solve the problem behind their backs.