Noam Scheiber writes today about two different views of the recession. The first, represented by Johns Hopkins economist Chris Carroll, relies on a model that says recovery depends on three things: wealth, unemployment expectations, and access to credit. As they recover, so will the economy: “The beauty of Carroll’s model is that it explains, with uncanny precision, consumer behavior going all the way back to the late ’60s. Those three simple variables — wealth, unemployment, and credit — tell you most of what you need to know about changes in the saving rate, and their predictive power has held up even through 2010.”

The second, represented by Japanese economist Richard Koo, says the data of the past 40 years is useless because we’re not going through a normal business cycle recession. We’re in the middle of a balance sheet recession, the same kind that Japan went through in the 90s: “Whereas Carroll assumes people base their saving decisions on the same factors both before and after the crisis, Koo says the way they make decisions beforehand tells you little about their behavior afterward. The crash doesn’t just pummel the value of their assets  (like housing). It creates a kind of psychological trauma that preoccupies them with paying down debt before they can think about borrowing again.”

(like housing). It creates a kind of psychological trauma that preoccupies them with paying down debt before they can think about borrowing again.”

So who’s right?

Early last year, economists at the San Francisco Fed observed that, if you extrapolate from the Japanese experience, the deleveraging process would take about a decade, during which time the saving rate would rise to about 10 percent, subtracting about half a percentage point from GDP growth each year (a huge amount when GDP is only growing by 2-3 percent). Slightly less alarmingly, the economist Allen Sinai has constructed an index of household financial conditions based on the measures of leverage we’re talking about. Sinai says the index recorded its all-time worst reading in early 2009 and estimates it’ll take another two or three years to get back to a level that’s healthy by historical standards.

We should be able to figure out whether we’re living in Chris Carroll’s world or Richard Koo’s over the next few six to nine months; the first big set of indicators — data on spending and saving from this year’s third quarter — should be out in the next few weeks. In either case, the economy probably needs more stimulus — 9.6 percent unemployment is much too high by any measure. But if it’s Koo who better approximates reality, the stimulus need could be acute at a time when GOP congressional gains have made it a political nonstarter.

OK, fine, I’m rooting for Carroll to be right. And I’ll even make a point in his favor: the Japanese have always been famous savers, so it’s quite possible that American savings rates aren’t going to follow the same trajectory theirs did.

Still, that just means we might be slightly better off than Japan, not different. What’s more, there’s a point in Koo’s favor that Scheiber doesn’t mention: Japan at least had the advantage of working through its recession during a global economic expansion. We don’t. In the end, Koo almost certainly has the better of this argument, but even if he’s only partly right, we are, quite plainly, fiddling while Rome burns. We know what we need to do to save our economy from a decade of ruinous stagnation, and we’re simply choosing not to do it. It’s almost beyond belief.

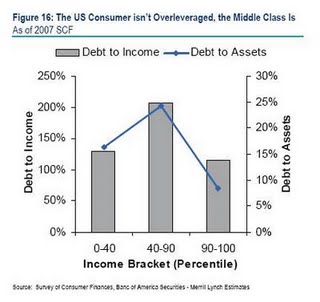

Via Mike Konczal, who has more on this, including a few charts like the one above.