Perhaps it’s the mark of a good book that after you read it, you begin seeing evidence for its thesis in lots of different areas. Since reading Tyler Cowen’s “The Great Stagnation,” I’ve been seeing a lot of support for a claim that I’d initially resisted: the idea that the technological advances of the 19th and early 20th centuries were far more important to both the economy and quality of life than what’s come since.

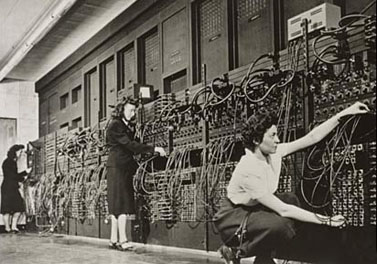

I myself never found this thesis hard to accept in the first place, but I’d toss in an additional aspect to ponder. Roughly speaking, I’d say there have only been three big GDP-busting inventions over the past few centuries: the  steam engine, electrification, and the digital computer. There have been plenty of related spinoffs (internal combustion engines, the internet) and plenty of important but smaller inventions (penicillin, radio). But the big three are the big three.

steam engine, electrification, and the digital computer. There have been plenty of related spinoffs (internal combustion engines, the internet) and plenty of important but smaller inventions (penicillin, radio). But the big three are the big three.

So in some sense, the problem here is with our expectations. World-changing inventions just don’t come around all that often, and when they do it takes a long and variable time for them to become integrated enough and advanced enough to have an explosive economic effect. Steam took the better part of a century, electrification took about half that, and computers — well, we don’t really know yet. So far it’s been about 60 years and obviously computers have had a huge impact on the world. But I suspect that even if you put the potential of AI to one side, we’re barely halfway into the computer revolution yet. To a surprisingly large extent, we’re still using computers to automate stuff we’ve always done instead of actually building the world around what computers can do.

In any case, regardless of how computerization unfolds in the future, it’s hardly surprising that we haven’t yet had a fourth great invention. They only come around once a century or so, after all. Give it time.