Steve Randy Waldman has a post today which, to simplify a bit, suggests that we’re seeing negative real interest rates today because (a) the rich have all the money, (b) there’s only a limited number of yachts the rich can buy, so (c) there’s a huge amount of money sloshing around the financial system looking for a home. When there’s a lot of supply and not much demand, prices go down, and that’s what’s happening to the price of money.

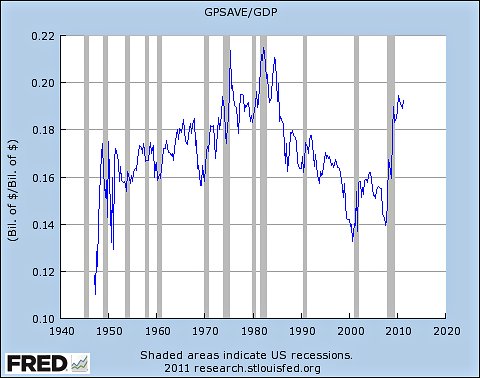

Paul Krugman objects, and shows us this chart of the national savings rate:

Krugman explains his objection like this: “I have a problem with this [story], for one simple reason: any such story, basically an underconsumptionist story, would seem to depend on the notion that rising inequality has led to rising savings. And you just don’t see that….Obviously it jumped up after the housing bust, but until then it was actually declining, and even now it’s below historic highs. I just don’t see how to make the underconsumption story work.”

I guess I see something different. Starting around 1980, which is exactly when income inequality in America started to gap out, savings steadily fell. Fundamentally, what this represents is two things: the rich accumulating most of the gains of economic prosperity while the middle class suffered from sluggish wage growth. The rich couldn’t really use that gusher of new money, so for 30 years they loaned it out to the middle class in increasingly Byzantine ways, and the middle class used these loans to sustain the steadily improving lifestyle they had gotten accustomed to. In 2008, this game of musical chairs came to a sudden end and the middle class stopped borrowing. And guess what? The rich still couldn’t spend all that extra money. If they could, the savings rate would have stayed low. Instead, it shot up. The middle class was borrowing less, and the rich, left with no customers for their money, couldn’t find anything to spend it on either. So now they’re saving it. In other words, the underconsumptionist story starts in 2008, not 1980.

I don’t want to pretend that this is the whole story. Yes, trade deficits play a role in all this. Demographics play a role. Oil plays a role. It’s crankery to insist on monocausal explanations for complicated problems. But I think that growing income inequality plays a role too. The rich are continuing to collect huge sums of money, but they can’t spend it all; they can no longer loan it all out; and there aren’t enough good real-world investments out there to sop it all up either. So it’s piling up and driving down real interest rates.

But this raises another question: why aren’t there enough good real-world opportunities to soak up all this money? Answer: Because there’s not enough expected future demand to justify expanding factories and hiring more workers. And why is that? Because for the past decade middle-class wages haven’t just been growing sluggishly, they haven’t been growing at all. But with wages stagnant and the great credit machine now turned off, middle-class consumption is necessarily going to be flat. That’s just arithmetic. And without growing consumption from the middle class, consumption just isn’t going to grow much.

For 30 years, the rich could ignore all this because Wall Street magically recycled income inequality and turned it into gold. That couldn’t last forever, though, and 2008 turned out to be the year the train ran off the rails. At this point, then, the rich have only a few choices. They can lose interest in the United States and find other countries to invest their money in. They can let the middle class wilt and just hang on to their riches. Or they can understand the dynamics of a mixed capitalist economy and figure out a way to return to an era of shared prosperity, where everyone gets richer at about the same rate and the middle class provides a growing market for the investment dollars of the wealthy.

I’d like to think that eventually the rich are going to choose Door #3. Unfortunately, there’s very little sign of that. It’s not clear to me how this story ends.