Dean Baker argues today that it’s wrong to view bad housing policy as the main thing holding back the economy. I think that’s right, and it’s a point worth making:

Dean Baker argues today that it’s wrong to view bad housing policy as the main thing holding back the economy. I think that’s right, and it’s a point worth making:

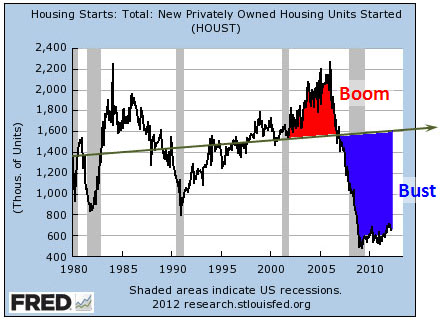

Bubble-inflated house prices created close to $8 trillion dollars of housing equity. The housing wealth effect implies that people would spend between 5 to 7 cents on the dollar of this additional wealth, creating between $400 billion and $560 billion in additional annual consumption….When the bubble burst, there was nothing to replace the lost demand. Residential construction fell by more than 4 percentage points of GDP ($600 billion annually in today’s economy). It fell below normal levels because the boom of the bubble years had led to record vacancy rates. Consumption plunged because the housing bubble equity disappeared.

….All of this seems clear and simple. We lost $1.2 trillion to $1.4 trillion in annual private sector demand. Some of this has been replaced by the federal government’s budget deficits, but not enough to fill the gap.

Even though I’m not quite as convinced as Dean that the wealth effect alone explains the Great Recession, it explains a lot. Home prices had to fall, and demand was always going to fall along with it, no matter how many underwater mortgages got rewritten.

One quibble, though: This doesn’t mean we wouldn’t have benefited from better housing policy early in the Obama presidency. Just because it wouldn’t have solved our entire problem doesn’t mean it wouldn’t have solved some of it. Better housing policy would have helped, and could have been an effective part of broad set of tools to boost the economy.

At this point, though, the bigger question is what to do going forward. Dean again:

The simple story is that we need a new source of demand to fill the gap left by the collapse of the housing bubble. In the short term that can only be the government. In the longer term it will have to be trade, which means a reduction in the trade deficit. That means first and foremost getting the value of the dollar down, but macho politicians in Washington don’t talk about a lower valued dollar. The folks on Wall Street don’t like it.

True enough. But I demand a follow-up post! The theory of trade deficits is murky enough on its own, but the actual practice of reducing trade deficits is positively swamplike — especially when the world is full of countries that also want to reduce their trade deficits and pretty much bereft of countries willing to give up their trade surpluses in order to help us out. So what should we do? On a purely mechanical, operational basis, how do we eliminate our trade deficit? No fair assuming that we’ll stop importing oil, either.