Illustration: Caitlin Kuhwald

At the South by Southwest Interactive festival in March, I attended a talk titled “Adding Value as a Non-Technical No Talent Ass-Clown.” It was given by Matt Van Horn, a 28-year-old executive at the social-media company Path. Path had generated a lot of buzz at the tech and media confab; it was recently valued at $250 million.

A crowd of about 100 was packed into the conference room, overflowing into the aisles. Van Horn stood stiffly in the center of the room, clipboard in hand, boyishly hip in a grey blazer, expensive-looking jeans, and eyeglasses with flashy white stems. He began with a story about chasing down a job at Digg, the once popular bookmarking site, shortly after he graduated from the University of Arizona. He said he’d won over Digg’s elusive cofounders by sending them “bikini shots” from a “nudie calendar” he’d put together with photographs of fellow students posing in their swimsuits.

Van Horn continued with some tips for hiring managers: He cautioned against “gangbang interviews”—screening prospective employees by committee—and made a crack about his fraternity’s recruiting strategy, designed to “attract the hottest girls” on campus. He seemed taken aback when nobody laughed. “C’mon, guys, we all know how it was in college,” he muttered.

Van Horn wasn’t even 10 minutes into the talk, but several clearly irritated women (and a couple of men) had gotten up and walked out. I joined them and tweeted from the hallway:

Biz dev VP of @path just cracked lame jokes re: “nudie calendars,” frat guys + “hottest girls,” “gangbang” at #swsx talk. Cue early exit.

— Tasneem Raja (@tasneemraja) March 11, 2012

Irritation ricocheted across Twitter among techies and media colleagues at the New York Times, Chicago Tribune, Webb Media, and other major outlets, and I fielded outraged questions and comments for several hours.

The surprising thing wasn’t that a 28-year-old “assclown” would channel The Social Network‘s Sean Parker—it was that Van Horn’s comments came on the heels of a whole series of tech-startup flareups over everything from advertising women as “perks” at a company event, to a marketing video featuring a woman clad in a corporate T-shirt and underwear, to a startup pitch session featuring a recurring photo of “leaping bikini-clad women.”

Many of the dozen or so people I interviewed for this story pointed to the rise of the brogrammer—a term that seeks to recast the geek identity with a competitive frat house flavor. The essence of it comes through in comments on the question-and-answer site Quora. “How Does a Programmer Become a Brogrammer?”: Brogrammers “rage at the gym, to attract the chicks and scare the dicks!” They “can work well under the tightest deadlines, or while receiving oral sex.” And they have their priorities straight: “If a girl walks past in a see-through teddy, and you don’t even look up because you’re neck-deep in code, expect to spend a lot of time celibate no matter how bro you go.”

The phenomenon has drawn media coverage and generated a Facebook page, a satirical Twitter persona, and YouTube videos demonstrating the Natty Light-loving, popped-collar-donning lifestyle. Some developers insist that it’s all just a big joke and doesn’t represent any actual streak in tech culture. But apparently it’s real enough for social-media analytics company Klout: The high-flying Silicon Valley startup came under fire last month for displaying a recruitment poster at a Stanford career fair that asked: “Want to bro down and crush code? Klout is hiring.”

But recruiter beware, warn some veteran observers: A bros-only atmosphere will hurt no one more than the startups that foster it. “We simply cannot afford to alienate large chunks of the workforce,” notes Dan Shapiro, a tech entrepreneur who sold his comparison-shopping company to Google and now works there as a product manager. Shapiro, who has blogged in the past about sexism in the tech industry, notes that “it is a widely understood truth that the single biggest challenge to a successful startup is attracting the right people. To literally handicap yourself by 50 percent is insanity.”

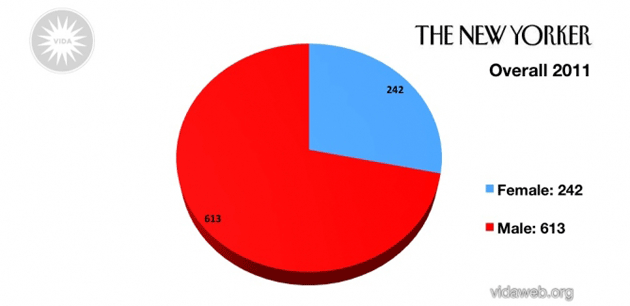

As it is, women remain acutely underrepresented in the coding and engineering professions. According to a Bureau of Labor Statistics study, in 2011 just 20 percent of all programmers were women. A smaller percentage of women are earning undergraduate computer science degrees today than they did in 1985, according to the National Center for Women & Information Technology, and between 2000 and 2011 the number* of women in the computing workforce dropped 8 percent, while men’s share increased by 16 percent. Only 6 percent of VC-backed tech startups in 2010 were headed by women.

Beyond the obvious workplace consequences—and potential legal fallout—of this imbalance, testosterone-fueled boneheadedness can also turn into a PR nightmare, especially in an industry awash in social media. Consider a recent fiasco involving Sqoot, a daily deals aggregator: In March the company advertised a hackathon in Boston with a flyer that listed “friendly female event staff” as one of the perks. A screenshot (first flagged by a man) got passed around on Twitter and Facebook, a flurry of blog posts followed, and sponsors started pulling out. One tweeted that Sqoot’s “marketing isn’t consistent with our company values.” Another wrote:

Hey all, we’ve officially withdrawn our sponsorship from the @sqoot event – we’re following up with them as well #disappointed

—LevelUp (@TheLevelUp) March 20, 2012

Sqoot apologized, while claiming the whole thing was a misunderstood high-concept joke intended to “call attention to the male-dominated tech world through humor.” Under pressure, they canceled the event: “Our words completely undermined our intentions and went further to harm the world we’re trying to have a positive impact on…As a young startup, we learned a lot today and are better people and a better company for it.”

Also in March, Reuben Katz and Christian Sanz, the cofounders of the online developer community Geeklist, got into a public spat on Twitter with a female coder named Shanley Kane. Kane had taken issue with a Geeklist marketing video that featured a woman dancing in a Geeklist T-shirt and her underwear. The video needed to be taken down, tweeted Kane, who describes herself in her Twitter bio as a “very nice girl, DPS princess, Warcraft junkie, Ruby/ROR [Ruby On Rails] weekend warrior, semiotician and beauty queen.” The three went at it over several hours in a Twitter shouting match during which Sanz told Kane she was being inappropriate, complained about her “aggressive tone,” and suggested that the fact that he is married and has a family show that he’s not sexist. Katz pointed out that Kane’s employer, Basho, was a Geeklist client—cc’ing Basho on a tweet implying that Kane was reflecting badly on both companies’ brands.

Additional reporting contributed by Nicole Pasulka.

Correction: The original version of this article relied on incorrect information from the National Center for Women in Technology stating that the percentage of women and men in the computing workforce changed between 2000 and 2011. Thanks to the blog Uncertain Principles for catching the error.

After the back-and-forth was captured by a technology editor at the Guardian and garnered over 70,000 views at the social sharing site Storify, Geeklist issued an official apology and took down the video. (You can see the behind-the-scenes version here.) The apology included a promise to create a “Women in Technology” advisory board for Geeklist and plans to devote the month of April to showcasing the work of female developers on its site. So far, this has resulted in a bare-bones web page with the names and pictures of 28 female web professionals and links to their Geeklist profiles. Reuben Katz did not respond to my inquiries about what other actions Geeklist has taken.

As for Path, after drawn-out negotiations with Van Horn’s handlers to get an on-the-record response about reactions to his SXSW talk, Van Horn emailed a statement through a representative: “Some of my words, used for instance to describe a group interview style, were, upon reflection, a bad attempt at humor and a poor choice of words, particularly when taken out of context. It was in no way my intent to offend anyone, of any sex, and I regret any offense I may have caused. “

In a prior phone conversation his representative had told me: “If you got to know Matt as a person, you would see that he isn’t sexist at all.”

But March wasn’t the first time Van Horn had used questionable material in a professional presentation.

At the startup-focused Grow Conference in 2011, his presentation included bikini-girl images from his calendar. He prefaced the slides with a laughing, “I’m sorry for being sexist. I apologize in advance.” (See video below.)

The most telling aspect of these incidents, says veteran Seattle developer Christy Nicol, is that none of the company leaders involved appeared to realize initially that they’d done something wrong. They had simply crafted messages aimed at young men, apparently assuming: Who else would be drawn to programming jobs? “It was the mindset seated deep in the subconscious that programmers are male,” she says.

Or at least that all programmers want to be in on the joke. “‘Brogrammer’ isn’t an exclusionary term,” wrote a commenter identifying himself as “Toronto Brogrammer” on a recent Businessweek story. “The female equivalent is called a ‘hogrammer’ and I have big respect for women that wear that badge proudly.” “Proglamming” and “brogramette” have also been tossed out, but none of the terms appeal to Alicia Liu, an San Francisco-based startup founder and web developer. “I’m still looking for a term for women that’s not derogatory, diminutive, or flippant,” she wrote on her blog.

Rachel Balik, a San Francisco-based tech marketer, wrote about the Sqoot and Geeklist incidents at Forbes, noting that in both cases many people, male and female, took a stand. “Yet for some reason,” she writes, “neither of these stories feel very positive. Maybe because it’s clear that these aren’t rare instances of sexism; these are just the people who were caught…Women put up with sexism, offensive remarks and intimidation all the time in the workplace, especially in male-dominated fields and at start-ups, where HR often doesn’t exist. Many of them may not be as fearless, determined and perceptive as Shanley. That means they’re often either suffering in silence—or giving up.”

Having worked at mature tech companies like Google and Microsoft, and having advised several young startup founders, Dan Shapiro says that people at the tech bellwethers don’t look kindly on brogrammer antics. And while big companies have robust employee policies and HR departments, small startups need more help. “Right now there’s not a lot of quiet pat-on-the-back or tap-on-the-shoulder coaching going on,” he says, but that’s what it’s going to take, particularly with so many inexperienced young men filling the ranks.

Not only that, notes Maria Klawe, president of Harvey Mudd College—which has revamped its computer science curriculum to attract more female students—but a company’s product is shaped by the people who make it. “If we restrict that to a rather narrow set of people, the outcomes are less desirable,” she cautions.

Consider Siri, the voice-activated “secretary” built into all new iPhones. She’s great at helping locate nearby prostitutes and drugstores stocking Viagra, but when blogger Amanda Marcotte tried to get her to find abortion providers and birth control, Siri came up empty. “Siri’s programmers clearly imagined a straight male user as their ideal,” Marcotte wrote, “and neglected to remember the nearly half of iPhone users who are female.” (Update: At the time, Apple offered assurances that the omissions were an unintentional glitch in a beta product.)

Adda Birnir, a 26-year-old programmer and media entrepreneur in New York City, watched the rise of the brogrammer aesthetic “with a mix of annoyance and exasperation” for several months before deciding to blog about it. She said she empathizes with a new breed of coders who are sick of the mainstream view that they are all undersocialized mouth-breathers living in their parents’ basements. “Brogrammers might lack tact, but they’re definitely marketing development in a way that appeals to a new subset of men,” she wrote. By recasting geekdom as an extension of the frat house, she believes, brogrammers are encouraging guys who might have headed to Wall Street to consider Silicon Valley. But if inclusion is the goal, she says, substituting “geek” with “bro” is equally problematic. “Because if there’s anything more alienating to women than a room full of geeks, it’s probably a room full of fratty guys.”

In response, Birnir says she is cofounding a new startup called Skillcrush, an online resource for women looking to learn code and feel comfortable doing it. “This stuff is scary enough if you didn’t grow up doing it, and you constantly feel so far behind and worried that you’ll sound dumb if you ask some really basic question,” she says. “And then you go to a conference panel and some guy is up there making misogynistic jokes? It just feels like at every point you’re getting the message that you’re not welcome.”

Here’s a round-up of brogrammer low-lights. The Storify might take a moment to load.

Storify by Maya Dusenbery and Nicole Pasulka.

The Rise of the Brogrammer: Can Silicon Valley Solve Its Sexism Problem?

As Mother Jones’ Tasneem Raja reports, the last few months have witnessed a series of flareups over sexism in the tech startup world. From SXSW presentations to online comment threads, brogrammer culture is everywhere and it’s pissing a lot of people off:

Storified by Mother Jones · Thu, Apr 26 2012 14:43:47