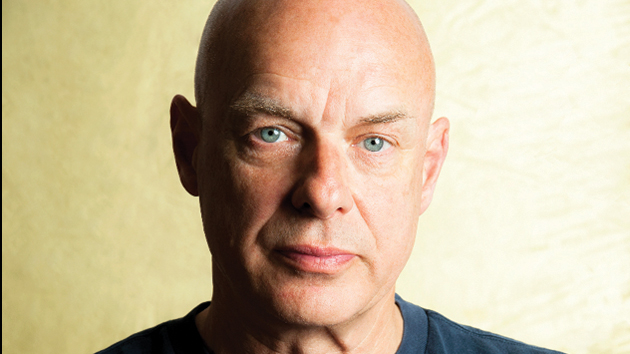

Eleanor Stills

Moby is tired. Since he released his 11th and latest studio album, Innocents, last October, the six-time Grammy nominee has been crisscrossing the country on tour and spinning DJ sets at electronic dance music festivals, not to mention starring in a video with Miley Cyrus and Flaming Lips frontman Wayne Coyne. But then again, he reminds me, “I’ve been traveling for the last 25 years.”

Indeed, the last quarter century has been an epic voyage for the 48-year-old musician. Born in Harlem and raised in Connecticut, Moby (born Richard Melville Hall, an actual descendent of Moby Dick author Herman Melville) has led a prolific, star-studded career that has included collaborations with Michael Jackson, David Bowie, Slash, Gwen Stefani, and countless other A-listers. Longtime fans will remember his punk-inflected days in the early ’90s, although most of us are more familiar with his quieter, cinematic sounds, which have graced Hollywood blockbusters such as Tomorrow Never Dies and The Bourne Identity.

When he isn’t writing, spinning, performing, or recording his music, Moby likes to raise some hell. A longtime vegan and animal rights activist, he has testified before Congress in defense of net neutrality and raised money to keep California from shuttering its domestic-violence shelters. But unlike his heroes—Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, and Chuck D among them—Moby usually steers clear of activism in the music itself. “Whenever I’ve tried to write issue-oriented or political music,” he explains, “it just hasn’t been good.”

In advance of our exclusive rollout of his latest music video, “The Last Day,” Moby regaled me with stories about (almost) rubbing shoulders with Prince, his activist origins, and coming to terms with his feud with Eminem. Check out the video below, and stay for our conversation.

Mother Jones: So, tell me what you’ve been up to this past year?

Moby: Innocents. What I love about making albums in the 21st century is that so few people buy albums! I can make an album without any commercial concerns whatsoever. There’s something sort of emancipating about that. An artist in 2014 who is thinking about album sales is either sadly deluded or has to make so many commercial compromises that it sort of takes the joy out of making music.

MJ: I can kind of sympathize with that as a journalist working both in print and online. So how does a musician make a living now?

Moby: Oddly enough, I think that the current climate enables a lot of musicians to do relatively well. Twenty-five years ago, you could be a bass player in a folk-rock band and do pretty well—that sort of means that you’re going to have to go get a day job. But a lot of my friends have learned how to write classical music for movies and produce other people and do remixes, and DJ and go on tour, and do all these different things. The more diverse their approach, the better their chances of actually having a career.

MJ: Like much of your work, the tracks on Innocence have a subtle quality. Is that intentional, to make music that contrasts with—as you phrased it at one point—the “bombastic” tunes we hear so much, in the Top 40 and whatnot?

Moby: Yeah, I have nothing against bombastic music, but when it comes to making albums, I’d prefer to make music that has a sort of vulnerable subtlety to it. That’s what I was trying to accomplish with the song and the video.

MJ: Over the years, you’ve collaborated with icons from Michael Jackson to Lou Reed. Who’s on your wish list?

Moby: Well, my main interest is just to work with people who have beautiful, interesting, emotive voices; I’m not too concerned whether someone is famous. But I guess the two people on the planet that I would love to work with: One is James Blake—I just think his voice is so touching and beautiful, and his approach to music is really interesting. And also, at some point in my life, I’d love to make an album with Prince. I love Prince. I’ve just never been interested in his fast, exciting music. But I love the ballads that he writes, and I think it’d be great if he made an album of just romantic, slow ballads.

MJ: Have you ever approached him?

Moby: Once, in 1988, I danced next to him and his security guard at a nightclub on 14th Street in New York City. I think it was called Nell’s. And then, about 12 years ago, I dated a woman who had grown up in Minneapolis and at one point had gone to a party at Prince’s house and turned down the offer to have a threesome with him. So that’s the only contact I’ve had. I can’t even call either of them technically a contact. It’s more just like six degrees of separation.

MJ: So, you talk about being drawn to subtlety, yet some of your earlier work had inflections of punk and was a lot louder. Was there a moment of transition for you?

Moby: When I was very young, I played in a punk-rock band, but I also studied music theory and classical music. In the late ’80s and early ’90s, I was playing a lot of electronic music but also playing drums in a punk band and writing experimental film music for friends of mine. I guess I’ve never seen the need to choose one type of music at the exclusion of another. That would feel kind of sad and arbitrary.

MJ: You’re credited, though, for helping usher electronic dance music into the mainstream.

Moby: In some ways it’s hard to see electronic music as a genre because the word “electronic” just refers to how it’s made. Hip-hop is electronic music. Most reggae these days is electronic. Pop is electronic. House music, techno, all these sorts of ostensibly disparate genres are sort of being created with the same equipment. So it’s sort of ironic for me to be associated exclusively with electronic music considering my background is punk rock and classical.

But in the early ’90s, when I was making techno and electronic dance music, it really felt like I was working in this maligned ghetto. A lot of music journalists wouldn’t take it seriously, so it’s been nice to watch electronic music rise to prominence. One of the things I love is how egalitarian it is. Up until the rise of electronic music, if you were a musician in Portugal or Germany or Italy or Japan, and you didn’t sing in English, you really were limited: You could be successful in the country where people understood your language. The world of electronic music is completely international. You have DJs from Finland making huge records for people in New Zealand, DJs in South Korea making huge records for people in France. By the fact that it doesn’t cost anything to make, and that it transcends language, nation, and barrier, it accidentally accomplishes a lot of really remarkable things.

MJ: So does Eminem now look foolish for claiming “no one listens to techno”?

Moby: I have a weird passing respect for him. I think he’s quite talented. And in 2004, he put out a song called, I forget what it was called, but he made this really powerful video that was a call to arms to get inner-city youth to vote. The fact that he dissed me—he said I was too old and nobody listens to techno—it’s sort of ironic, because now he’s quite a lot older than I was when he made fun of me for being too old, and clearly everybody in the world is listening to techno. But I learned a lesson: Never have public feuds with anyone who’s surrounded by people who carry guns.

The way the feud started was that I had assumed, as we got into the ’90s, that things like homophobia and misogyny were old, pernicious things that were sort of fading away. And I found it incredibly disheartening that in the late ’90s, suddenly pop culture became even more misogynistic and more homophobic, and so I criticized Eminem for having lyrics that were egregiously homophobic and egregiously misogynistic.

What I also found really odd, when I was criticizing Eminem for being misogynistic, is how few people came to my defense. I’m not trying to look for pity or sympathy. I was just surprised that so many people in the world of entertainment seemed to be okay with misogyny and homophobia as long as they were profiting from it. And I asked this one question, which was not necessarily for Eminem, but any musician: If you take a song that talks about committing acts of violence towards women and gay people, and if you change the subject and instead have songs about committing acts of violence against Jews and blacks, would the entertainment industry still be okay with it? Clearly the answer is no.

MJ: Your song “Why Does My Heart Feel So Bad” came out around that time. Any connection?

Moby: Not really. I always just made music that resonates with me emotionally. A lot of my heroes are people who’ve written very political, issue-oriented music—Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger and John Lennon and Neil Young and Chuck D. I wish that I could write politically inspired and issue-inspired music as well as Neil Young, but honestly, I just can’t.

MJ: But you’re a serious activist offstage. How did that all begin?

Moby: I was raised by very progressive intellectuals. At Thanksgiving and Christmas we’d sit around and talk politics and semiotics and art theory. It was instilled in me that every individual should do what they can to try and make things better. I have such a disparate list of causes, but the guiding principle is simply—and maybe this sounds obnoxious—that I’m offended by two things. One, when the actions of institutions or individuals involve the imposition of will upon people or animals. That violates my basic ethical understanding of the world. You can do basically whatever you want to, but the moment that you impose your will on another person or animal, that’s when we are allowed to say you have committed an ethical breach.

The other is: As a philosophy major, there’s one logical fallacy that really stuck with me. It’s called the is–ought fallacy. It states that because something is, it ought to be. That’s been used to justify slavery, women not being allowed to vote, children working in factories, cigarette smoking, the use of DDT. It’s so pernicious and asinine, but people still keep going along with it. When we look at factory farming, for example, the justification that most people have is, “Oh, well, we’ve always had factory farming, therefore we should continue to have factory farming.” It’s so illogical. The only people who benefit from it are the people who own the factory farms—everyone else is just lazy or complicit.

MJ: What other experiences or people have shaped your outlook?

Moby: Everyone from Jane Goodall to John Robbins, Peter Singer: I can’t even count the activist heroes I’ve had. Two of the things that I’ve learned over the years is how can you be an effective and sustainable activist? And I don’t mean driving a Prius. How can you apply yourself in a way that can be sustained over decades? Because I’ve seen a lot of my activist friends get burned out. And I see a lot of activists wasting time on actions that might not necessarily achieve their goals.

MJ: Example?

Moby: I’ve seen friends who are so well intentioned, and they have these great NGOs or charities, and at some point they decide to have a benefit concert. So they spend a year organizing a concert when they know nothing about organizing concerts, and at the end of the day either the concert doesn’t happen or it does, and they end up losing money and not drawing awareness to what they’re doing.

MJ: What would you consider a successful model of activism?

Moby: I think it’s really being clear-eyed and having goals that are in line with a rational understanding of your resources. If I’m fighting factory farming, I don’t have their financial resources, but I have media resources they don’t have. So for me to go up against Monsanto in a financial realm is absurd. But on a media level, a grassroots level, that’s where we win. Luckily, in the online platform insincerity becomes pretty apparent pretty quickly.

MJ: Which brings me to Gristle, your 2010 book of essays about factory farming and meat consumption.

Moby: I’ve been an animal rights activist and a vegan for 28 years. The entire time, I’ve asked myself: How do I best advance an animal rights agenda? At the time my friend Miyun Park at the Humane Society and I put out Gristle, there was this new wave of animal media from Food Inc. to Jonathan Safran [Foer]’s book Eating Animals to Michael Pollan‘s The Omnivore’s Dilemma. We wanted to put out a very factual resource that would be a companion to all of this other media. It’s not a fun book, and it’s not really a pop-culture book. It’s more academic, in a way.

MJ: Can we expect more books from you in the future?

Moby: I hope so. I’m not quite sure what. I’m writing a memoir right now about my life in New York from 1989 to 1999.

MJ: You’ve identified as a Christian. How do you square your religious views with your 2002 song “We Are All Made of Stars,” which seems to espouse evolution over creationism?

Moby: It’s a great question. In high school I was a punk-rock atheist. Then I became what I’ll call a sort of Kierkegaardian Christian. There was a time when I was a very serious Christian. Over time, I started becoming more and more aware of the vastness and complexity of the universe, which led me away from any sort of conventional Christianity. I realized the universe is 15 billion years old and unspeakably complicated. I still love the teachings of Christ, but I also believe that the human condition prevents us from having any true objective knowledge and understanding of the universe. All human belief systems are inherently flawed. If I had to label myself now, I’d call myself a Taoist-Christian-agnostic quantum mechanic. Also, there’s nothing in the actual Bible that limits a Christian in their appreciation of or interest in science. Anti-science is purely a function of ignorant fundamentalism.

MJ: Before I let you go, I’ve gotta ask: As a vegan who’s into sustainability, what’s your take on almond milk?

Moby: I make my own every now and then. It takes about 30 seconds and tastes great. But honestly, I’m not too concerned about almond milk.