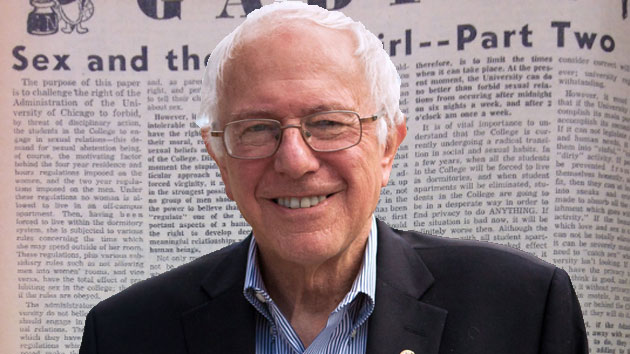

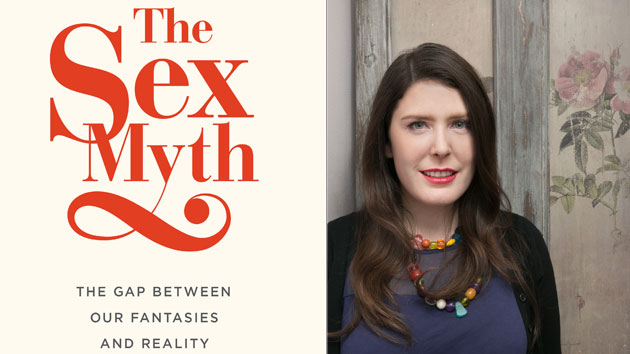

Photos courtesy of Simon and Schuster

When Rachel Hills tells men that she wrote a book called The Sex Myth, she typically gets one response.

“Hah, sex isn’t a myth to me,” she recounts, deepening her voice in mimicry. “Yeah, you definitely get the eye roll from the men.”

But for Hills, a New York-based magazine writer, the way people talk about sex is plenty mystifying. While working as an opinion columnist in her native Australia nearly a decade ago, Hills began to notice how the media seemed obsessed with the idea that young people only wanted no-strings-attached sex—and lots of it. “What was being said about young people and sex very much did not fit my own life,” says Hills. “And I felt a sense of insecurity around that.”

She wasn’t alone, as she soon discovered by talking to hundreds of people about the topic. Over the next eight years, Hills became something of a “sexpert” through her columns for Cosmopolitan and Huffington Post. Her research culminated in her first book, The Sex Myth: The Gap Between Our Fantasies and Reality, which went on sale Tuesday from Simon & Schuster.

So what is the Sex Myth? For Hills, it’s the misconception that people need to be good in bed in order to be “adequate human beings.” “We internalize this idea of sex as something that is constantly available and that everyone is doing, and if you’re not doing it, there’s something wrong with you,” she explains. The book intertwines anecdotes, scientific research, and occasional moments of self-reflection to make the argument that people too often allow their sexuality to be defined by factors outside themselves.

Here are some of the other myths Hills debunks:

Myth No. 1: If you’re not having tons of sex as a young adult, there’s something wrong with you.

During her younger years, Hills writes, “sex was an unspoken assumption…I, on the other hand, had made it not only through high school a virgin, but through four years of college as well.” But research shows college students might be having less sex than we are led to believe. For example, the Online College Social Life Survey, a project out of New York University, found that 72 percent of college students “engage in some kind of hookup at least once by their senior year.” But forty percent said they hooked up with three or fewer people during their college career, and only a third of the students had engaged in intercourse during their most recent encounter. One in five students hadn’t hooked up during college at all.

Myth No. 2: Your desires aren’t normal.

Hills interviewed young adults from all types of backgrounds across Canada, the United States, Australia, and the United Kingdom. The one thing they all had in common is that each felt that their sex life wasn’t “normal” in some way. Whether it was not reaching climax, not having sex frequently enough, expressing interests in kink, identifying as LGBTQ—no one was 100 percent sure that they were doing it “right.” Hills thinks the media plays a big role in fortifying this insecurity. Though progress has been made with shows such as Orange is the New Black and Transparent, the majority of mainstream entertainment portrays a very narrow spectrum of sexuality. “The ideal world that I’d like to see us move to, the liberated world, if you will, is the one where people aren’t made to feel shame about their sex lives, whether they’re being shamed for being considered too ‘slutty’ or ‘freaky’ or ‘weird’ or ‘prudish’ or too much of a ‘loser,'” Hills says. “So if you can remove that weight, then those decisions become less stigmatized.”

Myth No. 3: You’re not hot because Hollywood said so.

Hills points out that those who would be considered unattractive by Hollywood standards are also typically considered less sexual. Sex “serves as a proxy for our physical attractiveness and how well we fit in with the people around us,” Hills writes. The key to overcoming this attitude, she says, is introspection, and being much more critical of messaging about sex and how it applies to our own reality.

Myth No. 4: Men don’t worry about sex.

Perhaps the most surprising section of The Sex Myth is the chapter on male sexuality. Hills, a feminist, goes directly to where many feminist writers don’t—right into the hearts, rather than the hormones, of men. She writes sympathetically about unbidden erections and the pressure men face to perform sexually. “The absence of straight men from public conversations about sexuality also means that expectations of what men should do, be, and desire when it comes to sex often go unchallenged,” she writes. Hills argues that men are confined to a single definition of sexuality, which makes them “arguably more vulnerable to the Sex Myth than young women.”

The one weak spot in Hills’ analysis of male sexuality is her discussion of male sexual aggression in the context of rape culture. “The really ugly side of masculinity is a small part of it,” Hills writes. She adds that because rape is a well-covered topic at the moment, she didn’t feel compelled to dwell on it.

Myth No. 5: “Female sexual dysfunction” is all your fault.

How many jokes have been made about the female ability (and necessity) to fake an orgasm? Another aspect of the Sex Myth, as Hills describes it, is the pressure to turn pleasure into a performance. Hills thinks this impulse distracts from deeper issues. “If there’s anything ‘dysfunctional’ about our current approach to sex, it does not reside in our bodies,” she writes. But instead of drilling down on the nuances of female desire, companies would rather treat female sexual dysfunction as a problem that only medication can fix. As health journalist Ray Moynihan argued in a piece in the British Medical Journal, pharmaceutical companies are searching to “build markets for new medication” in the wake of Viagra’s financial success. Endless procedures and prescriptions have ensued, all of which lead to what one researcher describes as a “corporate-sponsored” disease.

So how best to avoid letting these myths creep into our consciousness and dictate our desires? Hills often turns to the antics of such comediennes as Amy Schumer and Tina Fey, who never shy away from sex as less-than-glamorous. “I feel like in making a joke about something, it creates permission for it,” she says. “The fact that you can say it makes it okay.”