When photographer Malcolm Linton and journalist Jon Cohen visited Tijuana in 2012, Linton was struck by the Tijuana River Canal, with its river of sludge and waste, surrounded by makeshift homes. The concrete embankments there are home to some of Tijuana’s poorest, many of them deportees, addicts, or sex workers. “It was an astonishing-looking place,” Linton says. “And the situation of the people appeared to be dire.”

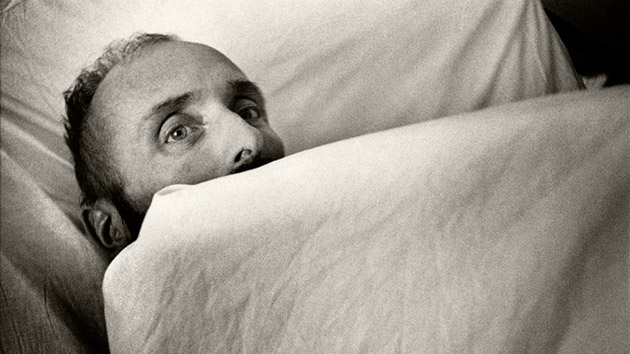

The following year, Linton and Cohen returned to the place known as El Bordo for a two-year look at the impact of HIV/AIDS in Tijuana. The result, Tomorrow Is a Long Time (published by Daylight Books), documents the lives of people most at risk for contracting the virus. (There’s also a companion video series.) “We wanted the book to show what happens to people over time, which is one of the hardest things to do in journalism because we’re often forced to race from story to story,” Cohen says. “Our aim was to describe people’s lives in enough detail to make you care about them, and these are people who for the most part live in the shadows of communities and are ignored or outright despised.”

According to researchers at the University of San Diego, roughly 0.6 percent of people in Tijuana are HIV-positive—around the same rate as in the United States. Yet among the most vulnerable groups, the virus is rampant. For the city’s estimated 10,000 injection drug users, HIV rates rise to around 4 percent; for female sex workers, 6 percent. Among gay men and transgender women, preliminary data show that 1 in 5 is infected.

Here’s more of what Linton and Cohen had to say about their new book, and the epidemic in Tijuana:

Mother Jones: To a casual observer, the news about HIV/AIDS usually sounds pretty good: Drugs are effective, infection rates are dropping, the crisis is mostly over. But the story you tell in the book doesn’t fit that narrative. What’s behind the mismatch?

Jon Cohen: The situation has vastly improved in Tijuana since anti-HIV drugs became freely available there about a decade ago. But too many people who either are at risk of becoming infected or live with the virus slip through the cracks. And this mirrors the situation in many places around the world. If you look at global figures from UNAIDS, 2 million people became infected last year. Fewer than half the nearly 37 million HIV-infected people in the world receive treatment. Harm reduction for drug users, which includes needle/syringe provision and opiate substitution, is offered relatively rarely outside of wealthy countries, and the lack of these services has lead to a recent explosion of spread in Russia and its former states.

I’ve been covering the epidemic as my main beat since 1990, and the advent of effective treatment has changed the world. I used to visit AIDS wards that had hundreds of people dying from HIV untreated. I never see that anymore. But things improved so dramatically because people the world over made noise about what was going wrong. Tomorrow Is a Long Time is in that same tradition.

MJ: How does the HIV/AIDS situation in Tijuana compare to that of other cities around the world?

JC: In sub-Saharan Africa, which accounts for 70 percent of the world’s HIV infections, the virus has spread widely throughout the general population, and transmission mostly is through heterosexual sex. Tijuana, like most everywhere else—including the United States—has an epidemic that has concentrated in “risk groups.” Also, as a border town, Tijuana is a magnet for migrants, and because it abuts the US, many of them are deportees. Migrants often have no safe place to live, and the vast majority are poor, especially if they’ve just been booted from the US after spending time locked up there.

There are some very good nurses and doctors working there, and the government provides free care to anyone who is infected, but there is no coordinated attempt to prevent and treat HIV infection. The shortcomings are especially stark, because you can see San Diego from downtown Tijuana. If you are infected in San Diego and attend a good clinic, the people who care for you will closely monitor how you’re doing with sophisticated tests of your immune system and viral levels. If you don’t show up for an appointment, an outreach worker may contact you. An HIV testing van sets up once a week in the heart of the city’s gay neighborhood, and distributes condoms and lube. If you’re positive at that van, they will link you to care and interview you about your sexual or needle-sharing contacts and try to reach those people and offer them tests. If you’re negative, they may recommend you take anti-HIV drugs to prevent becoming infected.

None of this exists in Tijuana. If you’re infected and attend the government-funded HIV/AIDS clinic, they send your blood to Mexico City to analyze how you’re doing and, until recently, whether you’re eligible for treatment. There’s no coordinated, aggressive testing program or outreach program, [preventative therapy] isn’t offered, and opiate substitutes are too expensive for most addicts.

MJ: At the beginning of the project, how did you begin building relationships in El Bordo?

Malcolm Linton: I actually tried to give up photography a few years back, because the market had gotten so bad. I began to retrain as a nurse. The offer of doing this book project came together at around the same time that I got my nursing license and graduated. When I went to Tijuana, I began by working as a volunteer nurse there for the UCSD project that was looking at the link between injection and HIV in Tijuana. So I got to know the people living in the canal because I would run the HIV tests on them much of the time. They’d come to the research office, and they’d meet me. Pretty soon I told them that I was also a photographer and that I was interested in doing this project.

The canal is foul. The ground is covered in used syringes, human excrement, bits of food, rats, and cockroaches. So I bought myself a small folding stool after a while. I’d simply go down there and unfold my stool beside a group of people who were sitting around shooting up. And sit there, for maybe 20 minutes, half an hour, exchange the odd comment, and that was about it. There wasn’t a need to say a whole lot. It was as much simply being there, and spending time, that earned me some sort of credibility.

MJ: How does Tijuana’s proximity to the US border shape the problem?

ML: Pretty much anything that makes people more socially vulnerable is going to feed into the HIV epidemic. Being deported is a strong risk factor. Typically in the case of Mexicans from that area of the country, they would have crossed the border with their parents as children illegally, when it wasn’t so difficult to cross the border. Then they grew up in the States, went to American high schools. Maybe they got involved in gang activity and drug use, and found themselves getting deported—at which point they’d simply be just dumped across the border. They wouldn’t necessarily know anybody in Tijuana. They might not even speak much Spanish. The canal is the first place that many of those people will go. There, they’ll encounter people using heroin. In the desperate situation in which they find themselves, they’ll start using it themselves, and it will temporarily solve their problems. But it will make them vulnerable to HIV.

MJ: What about the level of education around HIV/AIDS? How aware are people of the virus?

ML: Within Tijuana at large, people really aren’t very well informed about HIV at all. That obviously makes the problem worse because it creates the fear of the unknown, which feeds into stigma. One thing is that people don’t distinguish between HIV and AIDS. If HIV-positive people take their pills, they will pretty much cease to be infectious. That amazed people.

At the moment, there’s a kind of fatalism, whereby a very many people are infected feel that their life is ruined, and there’s really no solution, and they might as well die. We came across people like that. Maybe they don’t believe in the treatment or maybe they’re just too busy trying to survive, to get along in their everyday lives. Although there is theoretically support and treatment for everybody in Tijuana—if they’re infected, and if their CD4 level is below a target number—many of these people can’t lose a day’s work to go out to the government clinic because it’s so far out of town.

MJ: If the tools to fight the epidemic are there, why has Tijuana been unable to mount an effective response?

ML: Lack of outreach to these marginalized communities. And, perhaps, an impatience that they don’t do more to help themselves. Having said that, is it reasonable to expect people who are injecting heroin every day to think in terms of helping themselves, over a disease that isn’t necessarily causing them any symptoms at the time? Of course, it will eventually. But there needs to be more understanding, more outreach, less stigma, more education. And that’s not likely to happen if people continue to see those who are infected as people who need to be somehow swept away, eliminated, cleaned. That’s the word that people would continually use for the people living in the canal.

MJ: Who would use that word, “cleaned”?

ML: It was a word that the authorities would use, and you’d continually see it in newspaper reports. People would talk about cleaning the canal, as if the people who lived there were nothing but dirt. There will always be, I suppose, a feeling among certain parts of society that people who are infected deserve it, and that they don’t deserve help. But it’s an unhelpful attitude. However one feels about marginalized people who are infected, it makes sense to help them. Because that’s the only way to get a handle on the epidemic.

For me, the challenge became to take photos of Tijuana’s heroin users, sex workers, and other affected people that pulled no punches but also enabled readers to feel an empathy and intimacy with them. I was keen to avoid the suggestion that most of the people in the book were in no way responsible for their situation, but my aim was also to depict them as fellow human beings who, but for a past tough circumstances, bad luck, and bad decisions, were much the same as the rest of us. In an atmosphere where many in Tijuana’s social mainstream wanted marginalized people to disappear, I wanted to record that their existence and to represent them with as much depth and accuracy as possible.