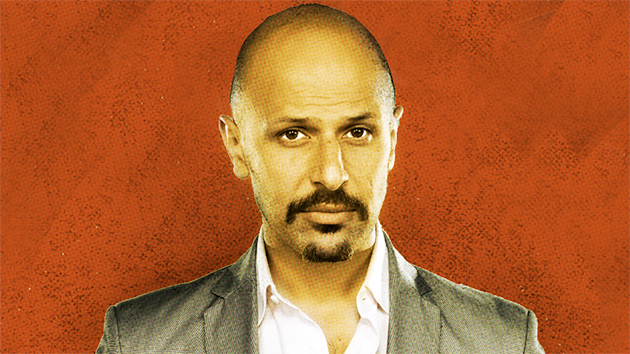

LONG BEFORE HE WAS CAST as the insecure coder Dinesh on HBO’s Silicon Valley, before he began voicing Prismo for the dystopian children’s cartoon Adventure Time, before Comedy Central gave him his own special, and before he began popping up on shows like SNL, Portlandia, and Inside Amy Schumer, Kumail Nanjiani was just a teenager in Karachi, Pakistani, obsessed with Western movies and television. He was particularly taken with The X-Files, the long-running 1990s sci-fi conspiracy drama starring Gillian Anderson and David Duchovny as Dana Scully and Fox Mulder, FBI agents investigating paranormal phenomena.

Nanjiani, now 37, would eventually make his way to Iowa’s Grinnell College and then work in tech for five years before having a go at stand-up comedy, a rare discipline in his homeland. His career kicked into high gear in 2008, after his autobiographical one-man show, Unpronounceable, drew high marks from critics. But Nanjiani never forgot his first love: In each episode of The X-Files Files, an ongoing podcast he launched in June 2014, he and a guest geek out on all things Mulder and Scully. His timing was spot on. Last March, Fox announced a new six-part X-Files miniseries that commenced on January 24. In the third episode, the agents track down a mysterious man-lizard. Portraying the animal control officer who helps them is none other than…You guessed it. You can also catch him in season 3 of Silicon Valley, which premieres April 24 on HBO. Here’s the trailer:

Mother Jones: The X-Files spanned nine seasons and 202 episodes. You’re now watching it basically for the fourth time. How is it different this time around?

Kumail Nanjiani: The first time I watched it, I identified with Mulder. By the third time, I connected more with Scully’s story. That was sort of a revelation. He doesn’t really change. He’s sort of crazy about this quest and that blinds everything else, whereas Scully sort of evolves. The fourth time I have to talk about it, so it forces me to be critical in the sense of trying to figure out why I like something, why I don’t like something, and what I think is good when it’s at its best. I have to pay a lot more attention. I used to watch it just to relax, and now it’s a little bit of a job.

MJ: It always frustrated me how Scully, after all she’s seen, remains so skeptical.

KN: Well, she’s a scientist. Just because you saw a vampire doesn’t mean that a snowman or a Loch Ness Monster also exists. With the alien conspiracy, maybe you could make the case that she should believe by this point. But the show does a pretty good job of making Scully’s lack of belief credible. They keep stuff away from her, and then once she does start believing, it becomes more of a personal thing.

MJ: What makes The X-Files more than just another TV show?

KN: It had been a while since a grounded, non-Star Trek sort of sci-fi thing really worked in the mainstream. And the idea of telling one long story over the course of many seasons. It also was one of the first shows to hang a plot on the DNA mapping and autopsies—science stuff. CSI, Cold Case, Bones: Now there are all these shows just about that. And Mulder and Scully make such a great pair. The chemistry is so undeniable.

MJ: In your very first episode, you talked about how The X-Files wasn’t something you could really broach with people.

KN: The podcast did start at a time people hadn’t been talking about The X-Files. I was talking at a bar to my friend, who was seven when he watched the first episode. He was like, “I feel like it’s time for The X-Files to come back into the conversation, with all the surveillance stuff and the NSA and all that.” I had a summer job that fell through, so I was like, “I’ll start just talking about The X-Files.” I found that there were a lot of latent fans that never really left. People were ready for it to come back.

MJ: When The X-Files first came out, you were 15 and living in Pakistan. What was your impression of America then, and how did the show feed into it?

KN: Usually in movies and TV shows you only see New York and LA. The X-Files was shot in Vancouver, and they would go to small towns and find different kinds of terrain to shoot in. Living in Pakistan, you didn’t have a sense of how huge and varied America was, geographically. I had visited once. I thought of it as this crazy, happy, exciting place where everybody’s rich and there’s stuff everywhere. Compared to Pakistan, it’s not untrue. Compared to Pakistan, the streets are paved with gold. But I was most excited about being able to see movies and TV shows right when they came out. That was crazy to me.

MJ: How did you land your role in the new X-Files?

KN: It was because of the podcast. The guy who wrote and directed the episode, Darin Morgan, had written a couple of my favorite episodes: “Clyde Bruckman’s Final Repose” and “Jose Chung’s From Outer Space”—which is everyone’s favorite. His brother is Glen Morgan, also an amazing writer who has written a bunch of my favorite episodes. So one day this guy was tweeting at me. I saw his name: Glen Morgan, and his avatar pic was the mom from the episode “Home.” He’d been listening to the podcast! So I interviewed him and I interviewed Darin, who actually hadn’t been hip to the podcast. We agreed to stay in touch. Eventually Darin emailed me and was like, “If I wrote you a part, would you want to be in an episode?” I waited as long as I could, which was like 30 seconds, and then wrote back, “Yes of course.”

MJ: What was going through your head acting alongside Gillian Anderson and David Duchovny?

KN: I didn’t want to start freaking out. I tried to train myself—I worked on the scene a more than I usually do and tried to look at it as a regular job. And then I landed in Vancouver and the driver picked me up and he handed me a folder. It was the “I Want to Believe” poster, and instead of “I Want to Believe,” it said my name. I called my wife. I was like, “Hey, you gotta talk me down!” What really helped was that David had known about the podcast and he had also watched some Silicon Valley. I think he knew how much this meant to me, so he went out of his way to be super nice. And Gillian was fantastic. You just kind of pretend they’re normal people and stay out of their way. There was once scene where Scully has come in where she has a flashlight out, and I remember being like, “Holy shit!” It’s crazy, these people are sort of icons to you—these heroes—and then for three days they’re just your co-workers. Then you leave and months go by and you go back to viewing them as icons and idols.

MJ: Let’s turn to your childhood. Your family was Shiite Muslim in a nation that’s overwhelmingly Sunni. Was that a big deal for you?

KN: Oh, yes. My mom told us never to reveal that we were Shia in school. You would find out that some other kid was Shiite and you would whisper, “Hey,” or you would see someone at the mosque and you’d be like, “Hey, that kid’s Shiite!” There was a lot of tension, a lot of violence in Karachi between Shiites and Sunnis. We were very aware that we were the minority. Their nickname for us was khatmal, which means bedbug.* And it wasn’t—I would go to religious sermons and people would be talking about anti-Sunni stuff. When I was a kid I was like, “I don’t think this is helping.” This priest guy gets to have guards around him, but he’s sort of getting all these other people excited about something that’s gonna get everyone in trouble.

MJ: Your parents were pretty religious. What limits did they place on your media consumption?

KN: Violence was fine, but nothing too sexual. For a while, we weren’t really allowed to listen to music on its own—it was okay if music was part of the TV or movie, but you weren’t allowed to just listen.

MJ: That must have been tough.

KN: Well, I just never knew. It’s not like I listened to music and then stopped. I still don’t have a real appreciation for music because I didn’t really start listening to it until my 20s. My wife knows everything about music, and I try and get her to educate me, but it’s just not part of my DNA.

MJ: You did, however, get into porn. In one routine, you talk about splicing porn scenes into VHS movies to pass along to your friends. What could possibly go wrong?

KN: Oh yeah, God. I was obviously not thinking with my head.

MJ: Any close calls, like someone’s little sister grabs a tape?

KN: Nothing like that, but I tell this story about how the power went out, and the tape got stuck in the VCR. I did tell my mom once, and it was very embarrassing and horrible. My parents knew I was doing it—they just didn’t know how to deal with it. So awkward.

MJ: How did you reconcile your porn-viewing with your religion?

KN: I didn’t. I felt very, very guilty about it. Obviously, sex was something that was repressed, I would feel these urges and then act on them and feel really horrible afterward.

MJ: Your family came to America not long after you arrived here for college. Why did they leave Pakistan?

KN: The plan was always to come to America, because Pakistan’s a scary place. They don’t have religious freedom. It’s very poor, and there’s a lot of violence and corruption

MJ: You studied philosophy and computer science at Grinnell. What compelled you to try stand-up comedy?

KN: I was extremely shy and had a terrible fear of public speaking. But I had fallen in love with stand-up too much to not give it a try. It felt like I had no choice.

MJ: You seem super relaxed on stage. How long did it take to get to that point?

KN: Six years. I was so nervous in the beginning that I actually built a persona around being nervous on stage. It wasn’t until I moved to New York that I decided to make a conscious effort to be myself.

MJ: How have your parents reacted to your career choice?

KN: They don’t quite know what to make of it, because it is a weird life. But I think they’re very proud of me. They don’t bring it up a lot in conversation. “Oh, that was good,” or “That was funny,” I don’t hear that. But when I go over to the house they have reviews of my stuff printed and framed. They never said anything about whether they liked my Comedy Central special, but then they gave it a really good review on Amazon.

MJ: You don’t push them on it?

KN: Honestly, if they said something was really funny, I would feel really awkward. It’s not in the parameters of our relationship.

MJ: Which is harder for you, stand-up comedy or acting?

KN: Acting, because I haven’t done it as long. On stage I just have to be myself. In acting you have to be so many other people.

MJ: What’s been your favorite small role?

KN: My first time doing Portlandia was wonderful. Fred and Carrie and the director were so cool. It’s the first time I felt funny as an actor.

MJ: You’ve referred to yourself as a beta male. Are they funnier than alphas?

KN: When I named my album Beta Male, it wasn’t a phrase I heard very much. Now I’ve found out that on Reddit and 4chan, it’s kind of a gross phrase. It’s some sort of weird “meninist” thing, and I want to distance myself from that horrible insanity. I just meant I am a very nerdy guy. I understand that it’s easier to cast me as a nerdy guy than an action star—although I would love to be an action star! I think being funny had something to do with feeling like an outsider, not feeling cool—insecurity. I think that feeling fuels a lot of funny people.

MJ: Is that what drives Dinesh, your character on Silicon Valley?

KN: He wants to be seen as cool, and the irony is that part of being cool is not caring that you’re cool. So that’s why he’ll never be cool. He’s an immigrant, as I am, and he’s also a little obsessed with success. He wants to prove to himself, but more importantly to the people around him, that he achieved the American Dream. To him, that’s dollar signs, it’s money, outward signs of wealth—and girls, that’s part of it too.

MJ: He strikes me as, you know, the 35-year-old virgin.

KN: Yes, exactly. [Laughs.] That’s exactly what he’s like.

MJ: How did you prepare for that role?

KN: I just remember in high school how desperately I wanted to be cool and how important it was to me. You take that and apply it to someone who’s older than that and it can be very funny.

MJ: Do you think Pied Piper, the show’s fictional startup, would survive in real life?

KN: No. We only hear success stories. You don’t hear about the hundreds and hundreds—the overwhelming majority that don’t go anywhere. This is a more realistic portrayal of what happens in startups, and I think that’s a much more interesting story than an overnight sensation.

*Correction: “Khatmal” means bedbug, not cockroach.