<a href="http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wea00529_-_Hurricane_Andrew_-_Buildings_on_the_Deering_Estate.jpg">National Weather Service</a>/Wikimedia Commons

This story originally appeared on Grist, and is reproduced here as part of the ClimateDesk collaboration.

Note to self: The next time you take the Climate Change Tour of Miami with Nicole Hernandez Hammer, bring Dramamine.

I’m sitting in the back seat of a rental car as Hammer, the assistant director for research at the Florida Center for Environmental Studies, careens around the Magic City like Danica Patrick. One of her graduate students rides shotgun, navigating with her iPhone.

Our mission for the day is to survey parts of this city that will be flooded as climate change continues to drive up the level of the sea. Hammer, who studies the impacts of sea-level rise on infrastructure and communities, has kindly agreed to act as my tour guide and pilot. I’m just hoping I can keep my breakfast down.

Our first stop is Star Island, where celebs like Don Johnson, Gloria Estefan, and Shaquille O’Neal have owned homes over the years. For a cool $18-$35 million, the local realtors known as The Jills would be happy to set you up with your own walled-in villa where you can sit in your rooftop hot tub and listen to the waves lapping a little too close to your foundation.

Next, we drive through Opa-locka, a neighborhood built in the 1920s by aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss, themed after the Arabian Nights. City hall, which sits on Sharazad Blvd., is a Moorish castle. The neighborhood is now mired in poverty and crime, and, adding insult to injury, it will sooner or later be mired in seawater: Even though it sits well inland, behind the coastal ridge, its low elevation means that water will flood in via the porous limestone on which the whole city is built.

We drive out to Virginia Key, where Miami-Dade County is in the process of doing a $1.6 billion upgrade on a sewage treatment plant that critics say could be vulnerable to catastrophic damage with just a couple of feet of sea level rise. South of here is the Turkey Point Nuclear Generating Station, which sustained serious damage in Hurricane Andrew in 1992.

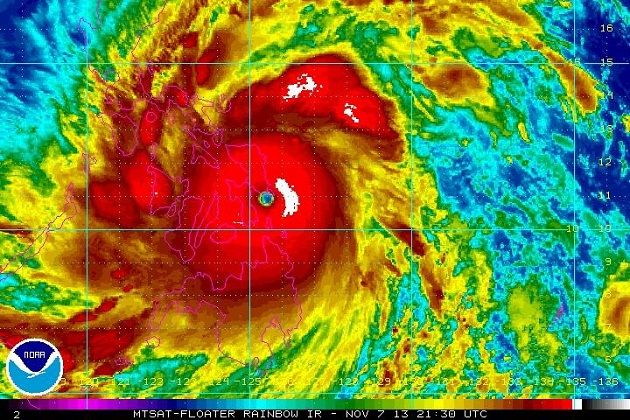

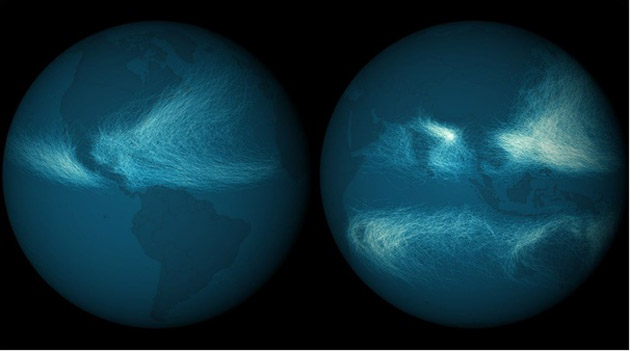

And therein, as the saying goes, lies the rub. Sea-level rise happens relatively slowly—it’s often measured in millimeters per year. But throw a major storm on top of rising seas, and things can get ugly in a hurry. Andrew, which slammed into the Florida coast on Aug. 24, 1992, was the latest case in point.

“I was here for Andrew,” Hammer says. “It tore our house apart.”

The statement brings me up short: “I’m sorry. Come again?”

“It was the day after Lollapalooza,” Hammer recalls. “I was 16.” She and her mother and two younger brothers — Oscar, 10 (who, incidentally, grew up to be this guy), and Mikey, 6—were home in their stucco, ranch-style house in a middle-class subdivision called King’s Grant. A storm was brewing off the coast, and an aunt and uncle and two young cousins had joined them. Hammer’s father, a physician, was at work at Baptist Hospital of Miami, about a 30-minute drive away. “We were like, ‘Oh, it’s a sleepover.’ We were joking and singing songs,” Hammer says.

The next thing Hammer remembers is the walls beginning to vibrate: “It started getting really loud. It was like a train running all around the house.” When windows started shattering, the family retreated to an inside hallway. When entire rooms began to collapse, they fled to the living room, where they huddled with the family’s dog, a pug named Bugsy, under a pile of overturned couches.

“My uncle took the dining room table and jammed it against the front door because it kept blowing in,” Hammer says. “The roof was coming off in chunks. It was pouring rain, and we were lying in about 6 inches of water.”

At some point during the mayhem, her father called from the hospital to see if they were OK. By some stroke of luck (or its opposite), the phone rang just as a window blew in, knocking the receiver off the hook. The last thing he heard before the connection cut out was his children screaming.

Andrew was eventually deemed a Category 5 hurricane, as strong as they come. It hit like a buzz saw, lashing the coast with 165 mile-per-hour winds, dumping eight inches of rain on Miami-Dade County, and kicking up storm tides reaching almost 17 feet. In the process, it tossed cars and boats around like a kid throwing a sandbox tantrum. The community of Homestead, which was hit head-on, was almost completely leveled. Some 1.4 million people lost power and 150,000 lost telephone service.

Hammer doesn’t know how long she and her family huddled in their living room before the wind finally subsided. She does remember it getting suddenly quiet—and hoping that it wasn’t just a temporary lull as the eye of the storm passed overhead. “We thought, if it’s the eye, if we’re only halfway through, we’re not going to make it,” she says.

Eventually, they heard a car pull into the driveway. It was Hammer’s father. Finding everyone soaked but alive (the pug made it, too—Hammer says one of her brothers kept him safe by lying on top of him), Mr. Hernandez took them to the hospital. “It was crowded and noisy,” Hammer recalls. “But what I remember most is the smell. There was this funk—it was hot-and-sick-people smell.”

All told, Andrew had done more than $25 billion in damage. In Dade County alone, it killed 15 people, destroyed more than 25,000 homes, damaged many more, and left a quarter million people temporarily homeless.

But it could have been much worse. The storm made landfall south of the city proper, missing touristy Miami Beach and the downtown area, as well as the Port of Miami and the airport. And for all its power, it was relatively small. “Andrew was a compact system,” says the summary on the National Hurricane Center’s website. “A little larger system, or one making landfall just a few nautical miles further to the north, would have been catastrophic…”

Since then, the stakes have only gotten higher. More than 5.5 million people now live in metro Miami, and the seas have steadily risen. According to a report released in May by the real estate data company CoreLogic, 132,000 homes in Miami, worth $48 billion, are vulnerable to hurricane-driven storm-surge damage. With a one-foot rise in sea level, those numbers jump to 340,000 homes and $94 billion. The World Bank ranks Miami as the most climate vulnerable city in the world.

Hurricane Andrew spurred a major overhaul of building codes in Florida and other coastal areas, but no one doubts that a direct hit from a category 5 storm could wreak massive havoc here. The last time a major hurricane hit Miami directly was in 1926. It’s only a matter of time, forecasters say, before the next one arrives.

After the chaos of Andrew had subsided, Hammer’s mother loaded the kids into the car and drove north to the Delray Beach area, where they started over from scratch. The kids never saw the house in King’s Grant—or what was left of it—again.

But Hammer’s mother has since moved back to the city, and Hammer says her work is motivated by a love for this place, however vulnerable it may be. “The scary thing is, in Miami, the storms come and then they go. We leave and then we come back stronger,” Hammer muses as she drives me back to my hotel. “But sea level rise is becoming the new normal. The way we adapt and become more resilient has to change.”

I’ll talk more about that, and about how environmental and economic factors are conspiring to force Miami to change, in future posts.