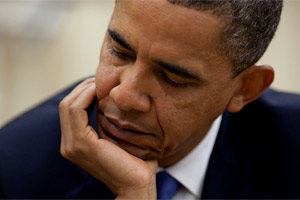

Flickr/<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/whitehouse/5062817085/">The White House/Pete Souza</a>

Obama’s tax compromise is now headed to his desk, having passed the House on Thursday night despite a late-breaking revolt by disgruntled liberals. The $858 billion deal marks the single most expensive piece of legislation of Obama’s presidency so far and has received more bipartisan support than any other major legislation, passing the House 277-148 and the Senate 81-19.

The deal is now being cast not only as a massive win for the president, but also as a pivotal step in “rebranding himself as Obama Classic – the circa-2008 with partisan discord,” writes Politico‘s Glenn Thrush. The Washington Post‘s Charles Krauthammer concurs: “Remember the question after Election Day: Can Obama move to the center to win back the independents who had abandoned the party in November? And if so, how long would it take? Answer: Five weeks.” The going assumption is that Obama has kicked off a new phase of non-ideological, centrist dealmaking that will clear a path for him in 2012 to win over the independent voters who broke for the tea party.

But two years from now, in the homestretch of his re-election campaign, Obama will be forced to take up the issue once more as the current extension of the tax-cuts expires. Obama will face a Republican Party that won’t be willing to broker the same deals and will be determined to do whatever it takes to defeat him. Incoming House Speaker John Boehner has already issued a challenge, declaring Thursday that the incoming GOP majority would be dedicated to “permanently eliminating the threat of job-killing tax cuts.” The current compromise notwithstanding, Democrats are expecting the president to come out swinging on the issue. The tax bill “gives the president the ability to say no when the GOP comes back and wants to extend these tax cuts…and I take him at face value,” Rep. Henry Waxman (D-CA) told reporters earlier this week.

If Obama does fulfill expectations and pushes for the expiration of the Bush tax cuts, he’ll be positioning himself as a partisan Democrat, not the “Obama Classic” of non-ideological bargains. Of course, he could end up triangulating, backing a watered down tax package—particularly if the economy continues to sputter, making tax increases a harder sell. Either way, Obama will forced into a starkly partisan battle, and he won’t have the political capital to rise above the ideological camps on both sides to strike a deal. The current triumph will be a distant memory to voters. If Obama can reinvent himself in five weeks’ time, as Krauthammer argues, his rebranding effort could dissolve just as quickly.