Here’s a statistic that should jolt you awake like black coffee with three shots of espresso dropped in: In the 2012 election cycle, 28 percent of all disclosed donations—that’s $1.68 billion—came from just 31,385 people. Think of them as the 1 percenters of the 1 percent, the elite of the elite, the wealthiest of the wealthy.

That’s the blockbuster finding in an eye-popping new report by the Sunlight Foundation, a nonpartisan transparency advocate. The report’s author, Lee Drutman, calls the 1 percent of the 1 percent “an elite class that increasingly serves as the gatekeepers of public office in the United States.” This rarefied club of donors, Drutman found, worked in high-ranking corporate positions (often in finance or law). They’re clustered in New York City and Washington, DC. Most are men. You might’ve heard of some of them: casino mogul Sheldon Adelson, New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, Texas waste tycoon Harold Simmons, Hollywood executive Jeffrey Katzenberg.

Those are a few of the takeaways from Sunlight’s report. Here are six more statistics (including charts) giving you what you need to know about the wealthy donors who dominate the political money game—and the lawmakers who rely on them.

(1) The median donation from the 1 percent of the 1 percent was $26,584. As the chart below shows, that’s more than half the median family income in America.

(2) The 28.1 percent of total money from the 1 percent of the 1 percent is the most in modern history. It was 21.8 percent in 2006, and 20.5 percent in 2010.

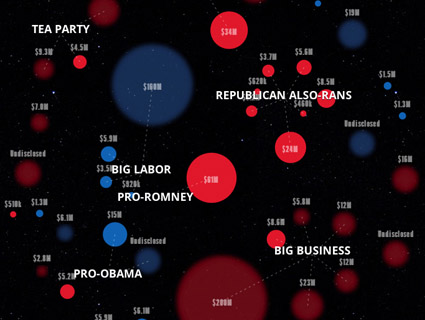

(3) Megadonors are very partisan. Four out of five 1-percent-of-the-1-percent donors gave all of their money to one party or the other.

(4) Every single member of the House or Senate who won an election in 2012 received money from the 1 percent of the 1 percent.

(5) For the 2012 elections, winning House members raised on average $1.64 million, or about $2,250 per day, during the two-year cycle. The average winning senator raised even more: $10.3 million, or $14,125 per day.

(6) Of the 435 House members elected last year, 372—more than 85 percent—received more from the 1 percent of the 1 percent than they did from every single small donor combined.

So what are we to make of the rise of the 1 percent of the 1 percent? Drutman makes a point similar to what I reported in my recent profile of Democratic kingmaker Jeffrey Katzenberg: We’re living in an era when megadonors exert control over who runs for office, who gets elected, and what politicians say and do. “And in an era of unlimited campaign contributions,” Drutman writes, “the power of the 1 percent of the 1 percent only stands to grow with each passing year.”