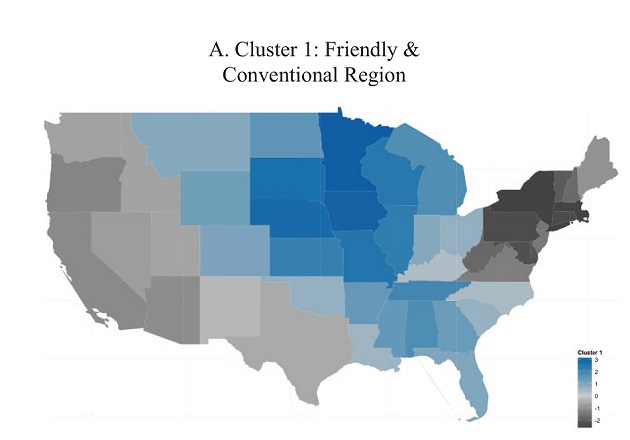

The "friendly and conventional"—in other words, conservative—region of the United States. On political maps, you're used to seeing many of these states colored red, not blue.American Psychological Association

Chances are you saw it. In fact, you may well have shared it. The Time.com version has been liked on Facebook 873,000 times as of this writing, with no signs of stopping.

I’m referring to a personality map of the United States, based on a just-published paper in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology by Peter J. Rentfrow and his colleagues. After administering a battery of personality tests to more than a million and a half Americans across the country, the study divides us up into three psychological regions: The “friendly and conventional” South and Great Plains; the “relaxed and creative” mountain states and West Coast; and the “temperamental and uninhibited” East Coast and New England states. Here’s the full image from the study, one that you’ve probably seen already:

But here’s the thing: Many people sharing these maps probably didn’t realize the full implications of what they were looking at. These images, after all, provide more than just stereotype-reaffirming evidence that New Englanders are aloof and Southerners are friendly; and more than just a fun game that lets you figure out what part of the country you should be living in based on your personality (Time.com‘s version). They also provide more evidence that political ideology, which varies regionally in the US in a way that is closely related to these temperamental regions, is, in substantial part, a psychological phenomenon. In other words: Politics is personality.

The key personality test used to construct the maps above, after all, was a study of the “Big Five” personality traits: Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism. This is a widely accepted model of studying personality (and no, it is not the same thing as Myers-Briggs). For many years, scientists have known that some of the Big Five dimensions are highly political. In particular, liberals tend to score much higher on Openness (interest in novel experiences and ideas), while conservatives score much higher on Conscientiousness (preference for order, stability, and structure in your life).

The study, and the resulting maps, put an exclamation point on this finding. After all, the “friendly and conventional” part of the US scores quite low on Openness in the study—much lower than either of the other two regions—even as it outscores both of the other two regions in Conscientiousness. The “friendly and conventional” region was also the only Republican-voting region of the three, and the most Protestant.

Granted, not every state with a “friendly and conventional” personality voted Republican in the last election, and there are some oddballs and outliers in other regions, too. But the overall trend is clear. The residents of more liberal and more conservative states differ in personality: In how open their residents are to new experiences, and in how much they prize order and stability in their lives.

How do these personality dimensions drive ideology? Well, put simply, people who are Open embrace change. Fixing healthcare with a big new system and way of doing things? Bring it on. By contrast, people who are low on Openness and high on Conscientiousness are interested in stability and just not messing with it. Yes, that’s right: The core of the left-right divide, which turns on one’s relative embrace of change versus the status quo, is rooted in an individual’s psychological makeup. And personality traits, in turn, are substantially heritable and run in families.

So how did we end up so divided? On the individual level, psychological differences between people have always been present, but geography seems to be becoming ever more important as a factor. In particular, the study by Rentfrow and colleagues suggest that people who are high on Openness are naturally more daring and experimental, and often all too eager to leave traditional parts of the country, where they know they just don’t belong, and relocate. Indeed, the Time.com version of the map, which lets you take a personality test and then figure out what state you belong in, in effect encourages precisely this sort of psychological mobility.

In other words, there’s a huge ideological sort going on, probably much of it driven by Open people leaving to be closer to other Open people—so they can all hang out at coffeehouses and complain about the Tea Party—and more traditional people staying behind where they prize family and community. And this, in turn, likely explains a substantial part of the US’s growing political polarization. Or as the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt just put it on our newly launched Inquiring Minds podcast, “For the first time in our history, the parties are not agglomerations of financial or material interest groups, they’re agglomerations of personality styles and lifestyles. And this is really dangerous….If it’s now that ‘You people on the other side, you’re really different from me, you live in a different way, you pray in a different way, you eat different foods than I do,’ it’s much easier to hate those people. And that’s where we are.”

Finally, it’s important to note that the psychological news here is not all good for liberals. Yeah, they’re open-minded. But as the study shows, a lot of them are also neurotic and not particularly agreeable. Describing people in the “Temperamental and Uninhibited” region, Rentfrow and colleagues use adjectives like “reserved, aloof, impulsive, irritable, and inquisitive.” Meanwhile, the emphasis on community, warmth, and social capital in the “friendly and conventional” region is hard not to admire.

The benefit of a psychological and personality-based approach to political differences is thus twofold. Not only does it help us understand why we’re so polarized and divided; it also teaches us what you can learn about how to live from the other side.