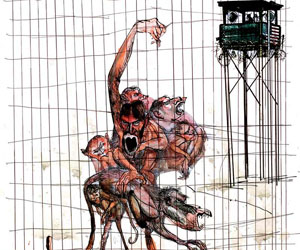

Illustration: Ralph Steadman | Cartoon by Steve Brodner

The era of Guantanamo Bay will come to an end, according to Joseph Margulies, a lawyer who has represented some of the detainees, when a judge utters the following words to George W. Bush: “Call your first witness.”

Margulies is not alone in believing that the only thing administration officials are more zealous about than fighting the Global War on Terrorism is any attempt to make public the murky processes they’ve cobbled together to wage it. The intricate legal scaffolding constructed by the Bush administration replaced something simple, basic, and beautiful: habeas corpus. Most Americans probably don’t know the meaning of that creaky Latin phrase and have been left with the impression that it is some boutique legalism that just ends up coddling terrorists. Actually, habeas is perfectly straightforward. It is the ancient right of anyone seized by the king to cry out from the dungeon and say, “I’ve been wrongly jailed!” Then you get a chance to prove your claim before a neutral judge, or back to the pokey you go. Habeas puts a basic check on the most fearsome power of the state and any citizen’s most primal fear—being locked away and forgotten, the civil equivalent of being buried alive.

This fundamental right was most famously codified in 1215 when, in the meadow of Runnymede, King John was forced to set his royal seal upon the Magna Carta, the seminal document that declared the rule of law above any man, including the king. The habeas hearing was among the first checks and balances. Habeas is an affront to the royalist impulse to consolidate all power under one king, or as Beltway ideologues call it these days, “the unitary executive.”

The problem with opposing habeas now is no different than it was eight centuries ago: You’re siding with the Sheriff of Nottingham.

Since 9/11, Bush’s officials have played a seven-year game of legal keep-away: filing new motions, changing jurisdictions, improvising legal proceedings on the fly, stalling, appealing, amending, and then appealing some more. So much so that the matter of habeas has now become a hot-button issue on the presidential trail. Barack Obama applauded the high court’s recent decision to extend habeas to detainees in Guantanamo; former pow John McCain said it was “one of the worst decisions in the history of this country.”

Many defenders of the Bush administration point out that detainees at Gitmo shouldn’t be receiving a habeas hearing because they are foreign combatants. To the Supreme Court, however, the key issue is not the rights of aliens but separation of powers. It challenged Congress’ audacity to limit this basic judicial power when the Constitution is clear that habeas can be suspended in only two situations—rebellion or invasion.

Another reason why habeas is being debated goes back to the original sin of the Bush administration’s catastrophic decisions on the battlefield. Ever since World War II, when the military has rounded up people after a battle, it has held brief hearings to determine if a prisoner was a legitimate pow or somebody picked up in error. Lots of mistakes get made in wartime, and commanders typically don’t want to be burdened with unnecessary detainees, so dealing with this matter right away—separating those who’ve taken up arms from those who got caught up in a raid—is essential. In the wake of the Geneva Conventions these battlefield tribunals have been referred to as Article 5 hearings.

In Vietnam, Article 5 hearings were typically held right there in the jungle. In the first Gulf War, 1,196 Article 5 hearings were held and only 310 detainees were classified as pows. And that’s typical. But not after 9/11.

Early on, White House Counsel Alberto Gonzales dismissed the Geneva Conventions as “quaint.” So everybody swept up was sent en masse to the camps. Then, the civilian leadership of the Pentagon made matters even more difficult. We bloated the enemy combatant population with a new technique: We started buying combatants.

We dropped leaflets out of planes, offering Afghans and Pakistanis as much as $25,000 to turn in Taliban and Al Qaeda fighters. Many of these leaflets landed in areas where an annual salary might be a few hundred dollars. This made it very tempting to turn in that neighbor whose goats always harassed your sheep. And that kind of feud settling happened. It will probably be years before we entirely understand just what kind of mishmash we made of our prisoner population by turning the fire hose of turbocapitalism on the Afghan outback.

Yet from the beginning, we’ve always had a clue. Donald Rumsfeld announced that the detainees were the “worst of the worst,” and General Richard Myers warned they “would gnaw hydraulic lines in the back of a C-17 to bring it down.” But as early as 2002, the commander at Gitmo, Maj. General Michael Dunlavey, complained  that he was receiving too many “Mickey Mouse” prisoners. A 2004 New York Times investigation found numerous officials who said that of the 595 detainees then held at Gitmo, maybe two dozen possessed any useful information. In 2006, a study of Pentagon filings on 517 detainees led by Seton Hall law professor Mark Denbeaux quantified it with hard numbers: Only 5 percent of the men at Gitmo had been scooped up by US forces, and only 8 percent were fighters of any kind.

that he was receiving too many “Mickey Mouse” prisoners. A 2004 New York Times investigation found numerous officials who said that of the 595 detainees then held at Gitmo, maybe two dozen possessed any useful information. In 2006, a study of Pentagon filings on 517 detainees led by Seton Hall law professor Mark Denbeaux quantified it with hard numbers: Only 5 percent of the men at Gitmo had been scooped up by US forces, and only 8 percent were fighters of any kind.

Overstating the number of hydraulic-line chewers at Gitmo has been a routine rhetorical tactic of Bush apologists. In his dissent in the latest case, Justice Antonin Scalia (who can’t get over the fact that other people can’t get over Bush v. Gore) hysterically noted that at least 30 released detainees “have returned to the battlefield.” Seton Hall’s Denbeaux looked at the evidence behind that number and found that the Pentagon counted as “returning to the battlefield” detainees who had participated in the documentary The Road to Guantanamo or had written a pro-habeas op-ed in the New York Times. When you narrow it down to those who’ve left Gitmo and actually taken up arms against the United States, according to Denbeaux, the number is five. And among those, it would be interesting to examine the use of the word “return.” What evidence does Scalia have that they weren’t goatherds radicalized by years of undeserved dungeon time?

Of course, there’s no better confirmation than the actions of the Pentagon itself. Even without abiding by habeas, the Pentagon has quietly released some 500 of the 770 detainees held at Guantanamo.

Over the years, as the courts have ordered the Bush administration to provide some kind of habeas-like hearing to the remaining detainees, the government’s lawyers ginned up something called a “combatant status review tribunal.” During a csrt, however, you can’t have a lawyer, know the evidence against you, or call witnesses except those “reasonably available.” The result? Hearings that are simply bizarre. Take the case of German-born detainee Murat Kurnaz, picked up in 2001. (See “Inside Gitmo With Detainee 061“) At his csrt, he learned that one of the official reasons for holding him was because two years after he was seized a friend blew himself up, except that because of bureaucratic incompetence, it wasn’t his friend at all, who was alive and well and living nonterroristically back in Germany.

Paging Terry Gilliam.

The csrts have become such a fiasco that one-fourth of the division of Justice Department lawyers charged with executing these tribunals have opted out. In the case of actual military commissions (the improvised “trials” that follow a csrt hearing), last year the chief prosecutor, Colonel Morris Davis, denounced the commissions as rigged, quit his job, and offered to testify on behalf of a detainee.

The reasoning for these complicated, shadowy processes—seizing prisoners in unorthodox ways, isolating them outside US jurisdiction, never bringing charges, then offering makeshift legal proceedings—is usually explained with the argument that 9/11 changed everything. Actually, Guantanamo is a case of history repeating itself.

Habeas corpus was the law of the land in England until the mid 17th century when royalist Cavaliers found themselves in a holy war with Protestant Roundheads. To the royalists it appeared that England was beset with terrorists, crazy fundamentalists who had no regard for human life—a.k.a. the Puritans. We remember them as folksy pilgrims with a garish taste in buckles. The British had other impressions. Even though the royalists themselves didn’t much care for Charles I, the idea of publicly executing the king was seen as an act of bloodthirsty terrorism on a par with, say, crashing a plane into a tower. When the pendulum swung back to royalism more than a decade later, King Charles II ascended the throne. Needless to say, the king’s lord chancellor—the head of day-to-day governing—a man named Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon, was suspicious of Puritans, suspicious of everybody. Terrorism makes you that way. So he seized anyone he fancied to be a potential threat and held them at detainment camps. And in order to avoid the bother of habeas hearings, he put them on an island off the British shore—some historians say it was the isle of Jersey—in order to deprive them of the protection of English common law.

Sound familiar?

In the end, Clarendon was impeached and fled in disgrace. Parliamentarians who thought Clarendon had gone too far—particularly one Lord Shaftesbury—passed the Habeas Corpus Act of 1679, reestablishing a balance between an executive who must make arrests in order to keep the peace and the individual’s right to challenge that arrest in court. Having learned the lessons of Guantanamo Bay more than 300 years ago, the 1679 act forbade the king from removing a prisoner to “Scotland, Ireland, Jersey, Guernsey, Tangier, or into Parts, Garrisons, Islands or Places beyond the Seas, which are or at any time hereafter shall be within or without the Dominions of his Majesty.”

And that was our inherited position, until George W. Bush became president. But the assault on habeas will end. Other Bush-era presidential powers will be challenged and debated. But not only will habeas be fully restored as a centerpiece of American jurisprudence, one might ultimately credit Bush indirectly for internationalizing the right, since that is a likely long-term outcome of his attempt to subvert it. The most recent court ruling broadened the reach of habeas—suggesting that no democracy should leave home without it.

Habeas is among the first great checks and balances in the very system of powers that we are said to be fighting for. With each Supreme Court reversal, with each appellate court smackdown, America walks the issue back, back to this elegant idea, back to this ancient right, back to habeas corpus. Even some of our most conservative judges have stepped up to affirm it. It’s only a matter of time before Congress does the same, restraining future presidents from ever again sending prisoners “into Parts, Garrisons, Islands or Places beyond the Seas.”