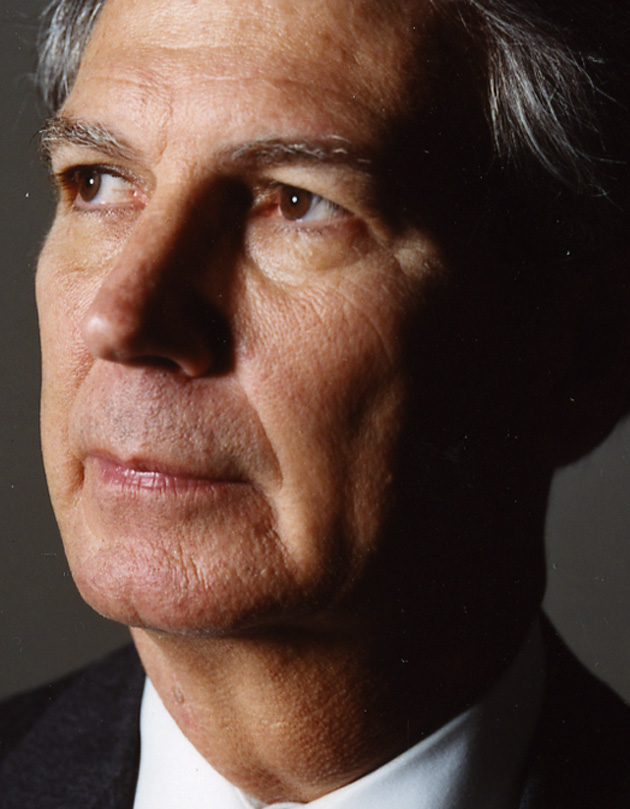

UNTIL THE CONGRESSMAN from North Carolina spoke, the hearings were proceeding routinely. The Armed Services Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives was convened on April 6 in a stately room in the Rayburn office building to consider the progress of the war in Iraq; much of the testimony was barely more animated than the paintings of deceased legislators adorning the walls. Richard Perle, a former Pentagon adviser and one of the war’s principal architects, had taken the witness chair. He was serene and unflappable as he answered questions about the Pentagon budget, oil prices, and the training of Iraqi troops.

Then the chairman called on Rep. Walter B. Jones. Glaring at the witness, Jones quoted a statement from Perle’s testimony suggesting that the administration had been misled in its assessment of Iraq by “double agents planted by the regime.” The congressman’s voice quavered as he demanded an apology to the country. “It is just amazing to me how we as a Congress were told we had to remove this man, but the reason we were given was not accurate.”

“I went to a Marine’s funeral that left a wife and three children, twins he never saw,” Jones said, his voice cracking as his eyes began to water. “And I’ll tell you—I apologize, Mr. Chairman, but I am just incensed at this statement.” He continued, “When you make a decision as a member of Congress and you know that decision is going to lead to the death of American boys and girls, some of us take that pretty seriously, and it’s very heavy on our hearts.”

Jones wasn’t the first erstwhile war supporter in Congress to have second thoughts; lawmakers like Senator Chuck Hagel and North Carolina Rep. Howard Coble preceded him in that reversal, and in November, most of the Senate’s Republicans voted for a resolution calling on the administration to “explain to the American people its strategy for the successful completion of the mission.” No less a figure than the Senate Armed Services Committee chair, Senator John Warner, a Virginia Republican and one of the Senate’s old bulls, has warned that the point is approaching when support of the war may no longer be politically tenable.

Yet among all the defections, Jones’ may be the most telling. The courtly 62-year-old Republican represents North Carolina’s flag-waving 3rd District, home to the U.S. Marine Corps’ Camp Lejeune. He is known to his constituents as a staunchly conservative Christian, and known to the nation and the world for his insistence, back during the lead-up to war in 2003, that House cafeterias replace French fries on the menu with “freedom fries.” He banished French toast, too. “A lot of us are very disappointed in the French attitude,” Jones said then.

Against that backdrop, Jones’ road to Damascus may seem especially long. But in truth, his conversion did not come about in spite of his conservative politics, his religious beliefs, his own military background, and his Marine constituency. It came about because of them.

FARMVILLE, NORTH CAROLINA, is a bucolic village of barely three square miles and fewer than 5,000 residents—including Jones, who was born here in 1943. The town sits at the center of the state’s tobacco belt, anchoring Pitt County’s role as the state’s largest producer of flue-cured tobacco. On a sunny October day, bright white balls of cotton glisten along the approach to the tiny downtown, a no-nonsense place whose blocks are lined with auto parts stores, body shops, and farm equipment vendors. Columned mansions, some in need of upkeep, sit beside neatly manicured Victorians, modest bungalows, and shacks. At the very heart of Farmville, outside the Town Hall, stretches a shaded expanse of green beset with benches, a fountain, a gazebo, and a plaque announcing the Walter B. Jones Town Common. The park is named after Jones’ late father, a political icon who represented Farmville and environs in Congress from 1966 to 1992.

Jones Sr. was a feisty Carolina Democrat, and virtually everyone here knows his name. He was “kind of a liberal Democrat, but he disguised it in populist rhetoric,” says Carmine Scavo, a political science professor at East Carolina University. A Baptist who believed in traditional family values long before the term became a GOP catchphrase, Jones sent his son to Virginia’s Hargrave Military Academy, whose mission statement promises a “wholesome environment in which the Christian faith and principles pervade all aspects of the school program.” The young Jones was a star athlete known for his ability to hit long-range jump shots, remembers Millie Lilley, whose husband later taught and coached at Hargrave. “He hoped to go to North Carolina State to play basketball.”

Hargrave did vault Jones into N.C. State, though not into the basketball program; it also planted the seed for his life’s first major conversion. One day on the Hargrave campus, Jones glanced through an open door and spied a fellow cadet on his knees, saying the rosary. “I was impressed by his devoutness,” he says. Jones began thinking and reading about Catholicism. “I didn’t so much get into the history of the church as I got into the ritual,” he recalls. When he was 31, he formally converted. “I haven’t missed a Sunday Mass in 30 years,” he says proudly.

Switching religious allegiances was not a minor decision at a time when many in the Bible Belt viewed Catholicism “almost like it was some sect,” says Lilley, who now runs Jones’ congressional office in Greenville. But Jones’ epiphany, she notes, was rooted in his personality more than religious dogma. “He likes the way Catholic services are organized. He likes knowing what to expect.”

“He knows the Bible,” adds Father Justin Kerber of St. Peter’s Catholic Church in Greenville. “I think that comes from his Protestant background.” Kerber is a soft-spoken, gray-haired priest from New Jersey who strongly supports President Bush. His church, a modern structure in sandy brown brick whose square cupola is filled with arty stained-glass windows, draws on a growing number of Catholics in eastern North Carolina, including Mexican immigrants and Yankee retirees. Every Saturday afternoon, when he is in town, Jones attends the 5 p.m. Mass, always sitting in the back pew.

Jones went from N.C. State to Atlantic Christian College, served in the National Guard, and settled into a job with a wine broker. “At the time I didn’t know a burgundy from a Bordeaux,” he says. His territory comprised all of North Carolina and parts of southern Virginia, a region not too distant from the Capitol, where his father was working. He rarely visited him there. “I never had the interest,” he says. “I’m a small-town guy.”

That would change, setting into motion the second major conversion of Jones’ life. In 1982, the district Democratic Party chose Jones to fill out the term of a state assemblyman who’d died. Suddenly, the conservative Christian wine salesman found himself following in his father’s political footsteps. With near-universal name recognition, he was reelected again and again. Then, in 1992, Walter B. Jones Sr. fell ill and retired from Congress. In the election that followed, young Jones ran for the seat his father had held—and lost in the primary to Eva Clayton, a liberal, labor-backed county commissioner. That defeat, and the suspicion that North Carolina Governor Jim Hunt had backed Clayton, soured him on the party of his father, his family, and most of his neighbors. What finally pushed him over the edge were his antiabortion beliefs.

“I talked to my father,” he says. “I told him, ‘I’m going to change my party affiliation.’ And—I give my right hand to my Lord and Savior—he said, ‘I understand that.'” A few months later, Walter B. Jones Sr. was dead. In the Republican landslide of 1994, his son rode Newt Gingrich’s “Contract With America” to a seat in Congress.

At first, Jones was a loyal soldier in Gingrich’s revolutionary army. He backed tax cuts, a redesigned welfare system, the Balanced Budget Amendment, and more money for the Pentagon. The handbook Politics in America described him as “one of the unreconstructed ‘true believers’ of the GOP Class of 1994.”

But, like the celluloid Mr. Smith, soon after Mr. Jones went to Washington he found himself disillusioned. The machinations of lobbyists, the power of money, and the ego-driven politics of the nation’s capital upset him. “Christ was a man of humility,” he says. “Washington is a city of arrogance.” Still, when George W. Bush declared a war on terror, and then took that war to Iraq, Jones was an early, firm, and vocal supporter. He believed what the Bush administration said about Iraq’s connections to Al Qaeda and about Saddam’s weapons of mass destruction, and he became one of the war’s strongest advocates.

The idea that catapulted Jones into the headlines back then came from Cubbies, a chain of restaurants in eastern North Carolina. In Greenville, Cubbies’ black awning spreads out over the corner of Evans Street and East 5th, and signs proclaim: “Voted #1 Cheeseburger and Hot Dog in Pitt County.” Inside, the place is packed with sports memorabilia and “Go Pirates” posters. Rough-hewn wood tables surround a comfortable bar. There are 13 Cubbies in North Carolina, including one in downtown Farmville and another in Beaufort, just outside the Cherry Point Naval Air Station. Neal Rowland, who owns the Cubbies franchise in Beaufort, first introduced “freedom fries” in February 2003, and soon customers were clamoring for them at every Cubbies. Jones “was inspired by it,” says Rowland. “He came in, and we chitchatted and talked.” Back in Washington, Jones prevailed on Rep. Bob Ney (R-Ohio), the chairman of the House Administration Committee, to rewrite the menus on Capitol Hill. With hindsight, it’s not one of his proudest moments. “I wish it had never happened,” he says now.

Just two months after the French fry incident came the event that would set off Jones’ third conversion—the memorial ceremony for Marine Sergeant Michael Bitz. Bitz was a 31-year-old amphibian assault vehicle driver who was killed in Nasiriyah on March 23, 2003, while trying to evacuate wounded troops. The young Marine left behind a wife, Janina, a two-year-old son, and a pair of newborn twins. His funeral was held on the grounds of Camp Lejeune, on the banks of the New River. Jones watched the Marines fold the flag that had draped the coffin and hand it to Janina Bitz as her toddler wandered close by. “She read from the last letter that he sent her,” he recalls. “I had tears running from my eyes.” The little boy, Joshua, dropped a toy, and a young Marine in dress uniform stooped to pick it up, handing it to the child. “And the boy looked up at him, and the Marine looked down, and then it hit me: This little boy would never know his daddy.” The tableau affected Jones in a way that he struggles to explain. “This was a spiritual happening for me,” he says. “I think at that point I fully understood the loss that a family feels.” Driving home to Farmville that day, grief swelled in him. “The whole way, 72 miles, I was thinking about what I just witnessed. I think God intended for me to be there.”

Jones began writing letters to the families of each and every U.S. soldier, sailor, and Marine killed in Iraq, a practice that he continues today. He’s written more than 2,000 in all. He works on them every Saturday, alone in his office in Greenville. He can bear to do only a few at a time. “I can do four or five letters, and then I have to stop and do something else,” he says. “And then I come back and do another five.” Outside his office on Capitol Hill stands a forest of placards titled “Faces of the Fallen,” bearing photographs of Americans killed in Iraq; there are so many that Jones’ staff has to rotate the placards. Those not displayed on easels in the hall lean against a breakfront by his desk.

Gradually, one letter at a time, Jones’ doubts about the war began to take shape. The failure of U.S. forces to uncover weapons of mass destruction gnawed at him, and the billions of dollars being spent added to his concern. He worried about President Bush’s inability to enunciate clear goals for the war. “In all the president’s speeches,” Jones says, “I’ve never heard the president say that there is an end point.”

Jones turned to those closest to him for guidance, including his pastor. Father Kerber recalls times that he and Jones would pray about important decisions, sometimes getting down on their knees in Jones’ congressional office. “He’s told me of the anguish he felt about the deaths in Iraq,” he says. “He would talk to me after Mass to say that his heart was so disturbed.”

Then—”as God would have it,” Jones says—his daughter, who works for the state agriculture department in Raleigh, gave him a gift that changed everything. For his long drives back and forth between Washington, D.C., and Farmville, a lonely trip down Interstate 95 that can take five or six hours, she presented him with an audiotape of James Bamford’s A Pretext for War, a scathing indictment of the Bush administration’s abuse of prewar intelligence that excoriates the neoconservatives who hyped the threat from Iraq. The revelations opened Jones’ eyes. “I was so concerned that I bought the book so I could highlight it.” Jones invited Bamford to lunch and then brought him back to Capitol Hill for an off-the-record dinner with two dozen members of Congress. Bamford, a former investigative producer for ABC News who has written widely on in-telligence issues, was impressed. “The vast majority of people in Congress, once they make a mistake, don’t want to admit it, which is why I have a lot of admiration for Walter Jones,” he says. “Until then, he had felt the emotion of the war and the casualties, but he hadn’t focused on the lies and the distortion and the exaggeration involved in the period before the war.”

That was last winter. Since then, Jones has met with numerous opponents of the administration’s Iraq policy, including conservatives such as General Anthony Zinni, the former commander of U.S. forces in the Middle East, and General William E. Odom of the Hudson Institute, a former director of the National Security Agency. He has sat down in his office with antiwar activist Cindy Sheehan.

Last June, along with Rep. Neil Abercrombie (D-Hawaii), Jones introduced a resolution presaging the one his Senate Republican colleagues would pass a few months later, but with one key difference: Jones’ version would have required the administration to develop a specific timeline for withdrawal from Iraq. He titled it Homeward Bound.

THE KETTLE DINER is as close as you’ll get to the center of daily social life in Jacksonville, North Carolina. It sits astride Marine Boulevard, the city’s main drag, which is lined with tattoo and piercing parlors, thrift stores, pawn shops, Saigon Sam’s souvenir shop, and Crazy Cuts (“Specializing in military haircuts”). Inside the Kettle Diner on an overcast fall afternoon, Mac McGee, a 26-year veteran of the Marines and a leader of the Military Order of the Purple Heart, is sipping coffee. McGee is 68—his hair, still buzz cut, is gray now. He served three tours in Vietnam. On Iraq, he says, “We need some sort of exit strategy. We don’t want another Vietnam, and let’s face it, that’s where we’re headed.” Do the boys at Camp Lejeune want out of the war? “They haven’t said it,” he says. “But I’m sure they’re starting to feel that way. I think they’re starting to get tired.”

Randy Reichler, who shows up at the Kettle later that afternoon, works at Camp Lejeune; he says that when Jones first announced his shift, the anger on the base was palpable. A thin, angular man with blue eyes and gray hair that tumbles down into sideburns, Reichler runs Camp Lejeune’s Retired Affairs Office, helping Marines plan their transition back to civilian life. Many people on the base “believe that Jones’ statements did hurt us,” he says, and some have accused him of wanting “to cut and run, give aid to the enemy.” But still, he adds, “some of them say, ‘You know what? We do need an exit strategy.'”

Around the district, reaction to Jones’ shift was similarly mixed. “It was about half and half,” Jones guesses—an estimate that dovetails with a statewide poll last summer by the Raleigh News and Observer, which found that only 42 percent of Tarheel voters felt the war had been worthwhile. Jones’ staffers recall fielding outraged phone calls from veterans, military retirees, and conservative activists. “The phone would ring, and you could tell what was coming just by their tone of voice,” says Lilley. There were murmurs about a primary challenge in 2006. But Jones made repeated trips to Jacksonville and explained his stance, holding no-holds-barred town meetings and confronting his critics.

The strategy worked. At the Barnes & Noble café in Greenville, Steve Moore, a beefy retired teacher, says that “what Jones did made my eyes pop open.” But, adds Moore—a longtime Democrat who has been voting Republican the past few years—opinion in Farmville is no longer uniformly pro-war. “I’m totally surprised,” he says, “at how much opposition to the war there is.” A few tables over, Bohdan Leskiw, whose brother served in the Marines, says pushing the president on a timeline for withdrawal “doesn’t sound like a bad idea. We can’t really send out men to fight and die in that situation.”

Brian Colligan, editorial page editor of the Greenville Daily Reflector, says he too has noticed a change. “Especially in the areas around the military bases, you tend to get the expected blind support of the troops and of the war, at least until recently,” he says, sitting in his sun-filled office at the paper. “Now people are beginning to separate the two. And it’s interesting that Jones has been on the leading edge of that change in sentiment.”

In Washington, the congressman’s shift has been greeted with less enthusiasm. “Lately, we’ve been hearing a lot from the ‘blame America first’ crowd,” says Rep. Robin Hayes (R.-N.C.), without naming Jones specifically. “It is wrong to cut and run on the Iraqi people.” The pro-war writer Chris- topher Hitchens called Jones a “moral and political cretin.” And when President Bush came to Fayetteville, North Carolina, to give a speech on Iraq last June, Jones was not invited.

The snub from the commander in chief didn’t faze the congressman, who has begun disagreeing with Republican leaders on other hot-button topics. He remains one of the House’s most visible Christian conservatives; among his legislative goals is a bill—prompted by his discovery of a children’s book on two kings who get married to each other—that would create local councils to monitor books in libraries and schools. But on other issues he regularly departs from the party line; he has clashed with the GOP leadership on environmental legislation and voted against the No Child Left Behind Act as well as President Bush’s prescription drug plan. The wave of scandals and investigations currently rocking Washington, he says, “might be an opportunity for a purge. The sun has got to shine.”

Mostly, Jones has been busy recruiting other Republicans to support his push to hold the administration accountable on Iraq. He’s won over at least a half-dozen. “All we’re trying to do,” he says, “is to start a debate about bringing an end to the war.” He insists he isn’t worried his independent streak might lose him favor with the White House, party leaders, constituents, or anyone else. Sitting in his Capitol Hill office, the Faces of the Fallen standing sentry in the hall, he has the air of a man utterly convinced of his decision. “I didn’t come up here to seek power or to get a chairmanship,” he says. “I want to do what I think my Lord wants me to do.”