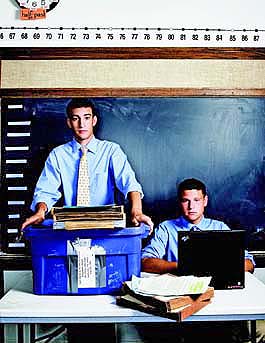

Photo: Peter Yang

Listen to an excerpt of Zach Baum debating the War on Terror (Stream | Download) and an excerpt of Jeremy Kreisberg debating torture (Stream | Download).

IT WOULD HAVE BEEN THE SPRING OF 1969, the Vietnam War in full swing, when a scrawny 18-year-old in a suit and tie and horn-rimmed glasses pushed a handcart stacked with 10 boxes into a classroom at Olympus High School, on the outskirts of Salt Lake City. Each shoebox was stuffed with four-by-six notecards pasted with evidence clipped from newspapers, magazines, and scholarly journals. As the young man and his partner unpacked their evidence on a small table at the front of the room, members of the other policy debate team looked on in horror. They’d only brought one shoebox. What they didn’t know was that 99 percent of the notecards in the Olympus team’s 10 shoeboxes were just props. Even at 18, the scrawny kid with the horn-rims understood the power of intimidation.

“Rove didn’t just want to win,” James Moore and Wayne Slater write in their book Rove Exposed: How Bush’s Brain Fooled America. “He wanted the opponents destroyed. His worldview was clear even then. There was his team and the other team, and he would make the other team pay.”

Karl Rove’s origins as a debater come as no surprise to anyone who has ever witnessed policy debate. Brutally competitive, the activity attracts extremely bright, fiercely ambitious misfits, many of whom go on to influential careers in politics or law. Along with Rove, alumni include presidents (Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, John F. Kennedy), speechwriters and political consultants (Ted Sorensen, Bob Shrum, Mark Fabiani), Supreme Court justices (Samuel Alito, Stephen Breyer), political gadflies (Michael Moore), and other smooth talkers (Oprah Winfrey, Brad Pitt).

There are many kinds of debate, but policy debate, conducted in teams, two against two, is widely considered the most hardcore. Interaction between teams is limited to four three-minute cross-examinations, or “cross-x.” For the remainder of the debate, teams take turns reading evidence prepared beforehand. In debate parlance, each piece of evidence is called a card and consists of a quote and a source for that quote. All evidence is scrutinized for possible weaknesses before being read in an actual debate. There’s total accountability within the round, meaning that an unanswered argument is considered a conceded argument. You win no points for empty rhetoric.

Aside from the spectacular speed at which debaters speak, it’s this emphasis on evidence that distinguishes formal policy debate from moderated political debates, to say nothing of what passes for debate on Sunday morning talk shows. The best debaters devote all nonschool hours to research, and weekends to tournaments. (SAT scores can suffer as a consequence; parents complain that their kids are spending too much time in the library.) Inside this petri dish, a uniquely self-referential culture thrives. Debaters all share the same jargon; the same cozy familiarity with Malthus, Foucault, democracy promotion, and nuclear war; the same problems with uncomprehending parents; even physical characteristics—a certain jumpiness, a tendency to route excess energy into nervous habits, like tapping feet or flipping pens. These similarities are reinforced on the national circuit, and especially over the summer, when teams congregate at debate camp.

On Cross-X.com, a debate forum, a thread titled “You know you’re a debater when…” provoked more than 500 responses, including: “You use subpoints in everyday conversation”; “You think your English Lit AP teacher is a moron because you can explain Foucault better than he can”; “When watching CNN, you think of ways to use the old guy’s speech in a debate”; “You stay over at a friend’s house, and in the morning, they say that you were debating in your sleep, and all you can think to say is, ‘Well, did I win?'”; “You’ve ever yelled at a librarian.”

Resolved: the United States federal government should substantially decrease its authority either to detain without charge or to search without probable cause. That’s the topic for high school policy debate over the last year, one broad enough to encompass everything from Guantanamo to searches of library records to wiretapping. These issues have been hotly contested in the public sphere, but who knew that across America a new generation of citizens was also furiously arguing about them, very often more intelligently, rigorously, and ruthlessly than the rest of us?

Intrigued, I recently took a train up from Manhattan to the New York state championships at Albany High. The team I had come to see, Edgemont High, from about an hour north of Manhattan, was one of the favorites to win.

Neatly dressed in crisp khakis and a blue oxford shirt, with close-cropped hair and swooping eyebrows that give him a surprised, almost avian look, Zach Baum is one-half of the Edgemont team. Jeremy Kreisberg, similarly attired in clothes that he is gradually dieting his way out of, is his friendly but formidable partner. Baum and Kreisberg—who’ve worked together since Baum’s last partner graduated in June 2005, an eternity in teenage time—seem ideally matched, and often refer to themselves as if they were an old married couple. Baum is a debating machine. His focus, as he ruefully admits, can at times seem almost autistic, or—given the fierceness of his eyes and the intensity of his manner—perhaps Vulcan. He’s an encyclopedia of evidence but can bungle the simplest social interaction. “In life I kind of rely on Jeremy,” he says, “but in debate it’s pretty opposite.”

Endlessly affable, and visibly more comfortable with himself, Kreisberg brings a much-needed sense of perspective to Edgemont. Where Baum is cocky, Kreisberg is modest; when Baum gets obsessive, Kreisberg offers the big picture. He is, in a way, Baum’s apologist. They’ve been researching this year’s topic since they attended debate camp at the University of Michigan in 2005.

“Your success is proportional to what you put into it,” Baum tells me during a lull before a match. “And we put so much into it.” He withdraws two finger-thick files from one of four enormous Rubbermaid tubs. The files are organized in anticipation of specific arguments that specific teams all across the country are known for running. One file addresses an argument granting the courts the power to hear appeals from Guantanamo detainees. Another addresses an argument in favor of banning polygraphs at the Department of Energy. “These are Zach’s children,” Kreisberg says. Baum nods. “All of these are 100 percent original research,” he says. “I didn’t get it from anywhere else.”

Buying evidence from college teams or debate websites is common, and generally considered perfectly ethical—it’s not the origin but the quality that counts. (Baum cites a college debater who made $1,000 selling a single file that addressed a rapidly changing political climate to high school debaters the week before a big tournament.) Edgemont, along with the rest of the debate world, follows a voluntary disclosure policy. If an opposing team asks what line of argument Kreisberg and Baum will take in an upcoming debate, they’ll gladly turn it over. The idea is not, as in a court of law, to catch your opponent off-guard, but rather to marshal as much substantive evidence as possible, in the interests of stimulating a more exacting debate.

“I think that’s the beauty of this activity,” Joshua Gonzales, an assistant debate coach from Michigan State, tells me. “There’s much less demagoguery and far more substance, and substance benefits everyone a good deal more. That might be something that the left can take away from this: There are substantive reasons to pursue the policies they want that are highly defensible, and I think actually probably appealing to the vast majority of the country. No matter how much passion or anger the current administration or conservatives or Fox News might stir up in them, over time better ideas triumph if they have committed, effective, and consistent advocates. I hope, at least. The reason I do it is, fingers crossed, that’s the sort of people we’re training here.”

Edgemont’s coach, David Glass, who cowrote this year’s debate topic, elaborates: “These kids are the people who are going to be running things in 20 to 30 years, and if I can help get a few of them to think responsibly, then cool. I mean, look at what Karl Rove is able to do.” Glass pauses, then adds, “He just does not care about the truth. That kid had a bad coach. Or no coach.”

Later in the season, when Glass, who has coached debate for more than 25 years, was inducted into the debate coach hall of fame, he expanded on this point to an audience of 300 kids: “We went through an election where gay marriage apparently was considered to outrank in importance the fact that we’re at war, the fact that there’s an all-time-high budget crisis… Because there was a clever debater, all of a sudden gay marriage was more important.… You have a choice. I’m sure you’ve all seen Star Wars. You can either decide to defend the dark side of the force, or you can defend the light side… You really have the ability to set agendas way beyond what you might right now believe.”

BY 11:30 A.M., Edgemont has eaten two teams for breakfast and is gearing up for round three, against a Brooklyn school set up by the ACORN community activist group. Compared to Edgemont, the ACORN team is casually dressed: a girl in a pink T-shirt, suede boots, and library specs; her male partner in jeans and a blue hoodie. As ACORN prepares its evidence, it’s clear that the girl calls all the shots. This does not bode well. A solid working relationship, with both partners contributing equally, is essential for any team’s success.

Eventually the judge arrives. ACORN is arguing affirmative—that is, in favor of the resolution. Each team is randomly assigned a position in the tournament’s first round, and thereafter the teams alternate. The affirmative team has the advantage of deciding what aspect of the topic to focus on. Most teams specialize in two or three arguments—extraordinary rendition, for instance, or border searches—which they run over and over again, improving them each time.

Kreisberg, his visored crew cut looking just licked, settles down behind his laptop, ready to note the key points of ACORN’s argument in a specially formatted Excel document. This is called “flowing,” and is employed mainly to make sure none of the opposing team’s arguments get “dropped,” or go unanswered. Baum sits to his left, rummaging through one of the Rubbermaid bins. The girl in pink claims a bin from her own evidence cache and staggers with it to the front of the room, where she drops it on a desk serving as a podium.

Having seen a RealVideo clip of policy debate, I thought myself—erroneously—ready for the real thing. The “aff”—the argument of the affirmative team—hits like a hurricane. It goes on for eight minutes, at times approaching the pure whine of a vacuum cleaner, sheer tone stripped of fricatives. Experienced debaters can reach speeds of 300 words per minute. Occasionally, the girl’s pace slows near the end of a passage, and a phrase emerges: “to prevent terrorism” or “crackdowns against political dissidents.” Then she revs up again, and the words blur like the fins of a plane prop. It’s like listening to a language poorly known, Spanish, say, in which an occasional familiar phrase slips through (trabajo, por supuesto), and you briefly feel on top of things, and then a moment later everything reverts to gibberish. Everyone else in the room appears unfazed: idly flipping through papers, scrolling through screens on their laptops, as if only a quarter of their attention is required.

Then, at the end of minute eight, the girl in pink subsides like a teakettle and returns to her seat. The fit has passed. From what I later gather, ACORN’s 1AC (first affirmative constructive) argued that the president should issue an executive order saying that detaining people without charge at Guantanamo violates the Geneva Conventions. The team mustered three main arguments in support of this plan: (1) Torture is inhumane and devalues all human life; (2) torture diminishes the United States in the eyes of potential allies in the war on terror; (3) failure to check Bush’s powers could lead to tyranny.

After a three-minute cross-x, in which Baum presses ACORN on why, if Bush did close Guantanamo, he wouldn’t just open another detention facility elsewhere, Kreisberg rises to deliver the counterattack.

“It’ll be one, two, three, four…four off,” he says, meaning off-case—that is, arguments unrelated to material presented in the 1AC. “Then tyranny. Torture. And then solvency.” This rough road map of the evidence he will read makes it easier for ACORN, and the judge, to flow his 1NC (first negative constructive).

Glancing at the other team, and then at the judge, Kreisberg sets his timer for eight minutes.

“Ready?”

And with that he storms into the 1NC, countering each of ACORN’s arguments and adding a few of his own, including the objection that passing the plan would constitute such a violent reversal of Bush’s existing policy that it would sap the president’s political capital and prevent him from passing the nuclear deal with India. The nuclear deal, he argues, would cement relations with India and guarantee U.S. influence in south Asia, which, in turn, would help prevent nuclear war between India and Pakistan. Therefore, his reasoning goes, endorsing ACORN’s plan basically opens the way for nuclear war. Sure, torture is bad, Kreisberg says, but nuclear war is worse.

By the end of the 1NC, the debate has divided, like the sorcerer’s broom, into a half-dozen sub-debates. On torture, Edgemont argues that the ends justify the means. Regarding detainees, it premises that if the Geneva Conventions were applied to Guantanamo, Bush would move the prisoners elsewhere. As for fueling anti-Americanism, the trend easily predates Guantanamo, and its origins are diverse. As for tyranny, Edgemont argues that endorsing an executive order would only reinforce presidential powers.

ACORN is strongest on the torture debate, but in cross-x it’s unable to dislodge Edgemont.

“If your mother was rendered somewhere,” the girl in pink challenges Baum, “would you rather fight the war on terror or would you try to save her?”

“Well, if it was my mom…”

“If it was anyone in particular, not just your mom, anyone…”

“The thing is,” Baum points out, “we’re not, like, rendering people’s moms.”

By the end, ACORN has tacitly conceded that torture is morally permissible if it saves lives, and this proves the team’s undoing. After awarding the win to Edgemont, the judge indulges in 10 minutes of pedagogy. To ACORN, he suggests that its 1AC could have benefited from more analysis, particularly the team’s assumptions about torture: “Are there things that should always be wrong?” he asks. “Are there things that we should never, ever allow? Because you have those arguments built into the 1AC and you’re not using them, like the slippery slope argument. Once we say we can torture one person, can we torture their family to get information? Can we torture the community? How about, to save 2 million people, can we kill 1 million?”

Untroubled by these weighty questions, Edgemont goes on to rack up one win after another, finishing with a 6-0 record. Later, in the raucous gymnasium, after the color guard has marched around itself a few times and “The Star-Spangled Banner” has been sung, Kreisberg and Baum are summoned from the bleachers to retrieve their trophy, a wooden plaque in the shape of New York state.

“This is nothing,” Kreisberg says with a shrug as we make for the doors. The real challenge, he says, will come in a month, at the “TOC,” or Tournament of Champions, where, over three days, the best teams in the country will slug it out.

ALL TEAMS MUST BE READY to advance or debunk both liberal and conservative arguments, but, Rove notwithstanding, policy debate leans to the left, largely because many coaches are college students. This can sometimes give rise to intellectual grotesquerie when high schoolers, in thrall to college kids obsessed with Foucault or Agamben, embrace outlandish post-structuralist arguments.

Edgemont reliably comes out against such arguments. Kreisberg is particularly good at staring them down. In Edgemont’s final round at Albany, two kids from Monticello High tried to use Agamben to argue that giving rights to immigrants is bad. The argument led to the following exchange during cross-x:

EDGEMONT: Let’s go through a few examples. The United States removes slavery. That gave rights to a specific group of people. Good or bad?

MONTICELLO: We’ll just advocate that it’s a bad advocacy in the round.

EDGEMONT: It was bad that the United States ended slavery?

MONTICELLO: Agamben’s argument is that the people who were being enslaved were being exploited because they didn’t have rights. Once they were given rights, the exploitation shifted to another group.

EDGEMONT: And then the United States passed the Civil Rights Act. I don’t understand why…

MONTICELLO: Right, and then it keeps on shifting to other groups.

EDGEMONT: And the status quo is worse than slavery?

MONTICELLO: Agamben argues…

EDGEMONT: Are you honestly saying this right now?

The exchange highlights a key difference between debate and mainstream sports. Football is physically dangerous but intellectually safe. With debate, it’s the reverse. The issues are real, and sometimes their subordination to the exigencies of the game are faintly objectionable. Employing the bare calculus of which argument is the most winnable, debaters will not hesitate to advance positions that they’d never suggest outside of a debate round. The very structure of debate encourages this dissociation—complete accountability within the round, but zero outside of it. “People have won debate rounds arguing that human extinction is good,” Kreisberg says, “because humans are ‘a cancer upon the earth.'”

But Jeremy Sklaroff, another member of the Edgemont team, says post-structuralist arguments—critiques of power, language, hegemony—have their place: “What about our structure of government or systems of power has created the crisis we’re in right now, where we’re trying to choose between civil liberties and security? Why is there a dichotomy between those two ideas? And since there is, what role do we play in creating that sort of system, and what can we do to get rid of it?”

But Baum and Kreisberg remain unrepentant literalists. “Agamben is just dumb,” Kreisberg IM’d me. “I’m sorry, but ending slavery, although maybe politically convenient, was a good thing. Even Foucault admits there’s no way out of power relations.”

The tournament of champions is held every year, as it has been since 1972, at the University of Kentucky-Lexington, within days of the Kentucky Derby. Unlike the Derby, there are no spectators, since no one could possibly follow the action. The atmosphere can only be described as grim, like the last days of school, when exams have reduced the students to pale, muttering versions of their former selves. Clutches of debaters and coaches gather in the hushed halls to discuss strategy. The classrooms are littered with empty cans of Red Bull.

“I love this,” Baum says. “You don’t sleep. You don’t eat. And your brain is basically being, like, raped the entire weekend.”

Edgemont is staying at a local Ramada, where, in the dim, carpeted banquet hall, the final rounds will be held. Their room is a disaster area, the floor blanketed by highlighted evidence cards, bath towels, and luggage. Rubbermaid tubs—by now there are six of them—disgorge reams of research while four laptops busily suck down more data from the hotel’s wireless connection and two printers struggle to keep up. “We’ve already gone through three print cartridges,” Baum says happily. “Well, we’ve gone through—how many—like, two and a half for this printer, and that printer we’ve gone through two.”

Though the tournament doesn’t begin until tomorrow morning, Edgemont has been encamped since yesterday. “Our biggest rival this year is probably this school Greenhill, near Dallas,” Baum says. “They knocked us out of the Glenbrooks, which is this tournament in Chicago. They knocked us out of Montgomery Bell Academy, in Tennessee, and they knocked us out at Harvard.”

When morning comes Kreisberg and Baum discover they’ve been assigned to debate Greenhill in the first round, at 8 a.m. Greenhill is composed of Matt Andrews, a junior with pushed-up sleeves and hunched shoulders, and Stephen Polley, a tall, poky kid wearing a baseball hat that, in the course of the entire tournament, he never once removes. The debate takes place in a small lecture hall with four tiers of concentric desks. Besides the two teams, myself, and the judge, there is no one else in the room, which could easily accommodate 200.

Kreisberg stacks two tubs on the dais. Greenhill has just delivered its 1AC, a well-muscled attack on unwarranted searches of library records, and Kreisberg has eight minutes to parry. Tapping his cards straight on the top of the tub, he glances at the judge, sitting high in the fourth tier, and then at Greenhill, to his right. In the next room over, another debate has also begun, and the muffled rant beyond the blackboard sounds like a case of domestic abuse. Kreisberg checks his timer.

“Everybody good?”

The day is grueling, even for an observer. As on a campaign trail, stamina is essential. Each debate lasts about an hour and a half, and it becomes increasingly difficult to understand what the debaters are saying, much less process their arguments and formulate strategies in response. The halls are aswirl with rumors about who’s running what, and who beat whom. By mid-afternoon, Edgemont has won one debate and lost two, including the first one, to Greenhill.

The team’s final match of the day pits it against Christopher Columbus High, from Florida. If Edgemont loses this debate, it’s out. In the hallway, Sklaroff offers Baum a few words of encouragement. “Zach, you’re going to poop on this team,” he says.

Alas, it is not to be. The judge finds against Edgemont, on the grounds that it has no answer for Columbus’ “hollow hope” argument, which essentially says that designating the Supreme Court as an agent of change creates a hollow hope that change will in fact happen, when there is no guarantee that it actually will. (“After Brown v. Board of Ed,” coach Glass later explains, “they were like, ‘Okay, everything is solved.’ But of course it wasn’t—until the Civil Rights Act, which was legislative.”)

Kreisberg suggests I give Baum some room. “He takes it pretty hard,” he says. “This is his life.” And Edgemont still has to debate—at least until elimination rounds begin on day three. By 8 p.m. on the third day, only two teams are left: Glenbrook-South, two-time TOC winner, and the dreaded Greenhill. At precisely midnight, before an audience of 60 vanquished debaters sitting scattered beneath the enormous chandeliers of the Ramada’s banquet hall, Greenhill is declared the victor in a 3-0 decision.

The news comes as a blow to Edgemont. Still, Baum and Kreisberg remain upbeat. From my first interactions with them back in Albany, it was clear that they took the long view.

“I want to be elected to very high office,” Baum told me.

“Zach’s going to be the president,” Kreisberg clarified, and, squinting, one could easily see Kreisberg as Baum’s VP—although, with his easy charm, he might make a better press secretary.

In that case, I offered, Baum should keep his record clean.

“No more drinking,” he agreed. “If some of those pictures get out I’m…”?

“Screwed,” Kreisberg put in.

“Career is over before it started.”

“Well,” Kreisberg observed, “it didn’t hurt Bush. Actually, it probably worked in his favor.”

To hear audio of an Edgemont debate, visit motherjones.com/debate.