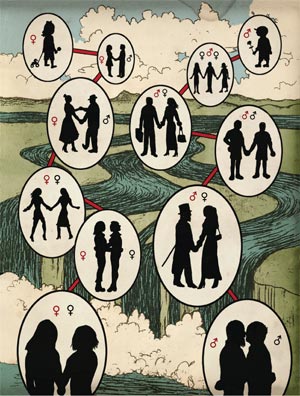

Illustrations by: Jonathon Rosen

When he leaves his tidy apartment in an ocean-side city somewhere in America, Aaron turns on the radio to a light rock station. “For the cat,” he explains, “so she won’t get lonely.” He’s short and balding and dressed mostly in black, and right before I turn on the recorder, he asks me for the dozenth time to guarantee that I won’t reveal his name or anything else that might identify him. “I don’t want to be a target for gay activists,” he says as we head out into the misty day. “Harassment like that I just don’t need.”

Aaron sets a much brisker pace down the boardwalk than you would expect of a doughy 51-year-old, and once convinced I’ll respect his anonymity, he turns out to be voluble. Over the crash of the waves, he spares no details as he describes how much he hated the fact that he was gay, how the last thing in the world he wanted to do was act on his desire to have sex with another man. “I’m going to be perfectly blatant about it,” he says. “I’m not going to have anal intercourse or give or receive any BJs either, okay?” He managed to maintain his celibacy through college and into adulthood. But when, in the late 1980s, he found himself so “insanely jealous” of his roommate’s girlfriend that he had to move out, he knew the time had come to do something. One of the few people who knew that Aaron was gay showed him an article in Newsweek about a group offering “reparative therapy”—psychological treatment for people who want to become “ex-gay.”

“It turns out that I didn’t have the faintest idea what love was,” he says. That’s not all he didn’t know. He also didn’t know that his same-sex attraction, far from being inborn and inescapable, was a thirst for the love that he had not received from his father, a cold and distant man prone to angry outbursts, coupled with a fear of women kindled by his intrusive and overbearing mother, all of which added up to a man who wanted to have sex with other men just so he could get some male attention. He didn’t understand any of this, he tells me, until he found a reparative therapist whom he consulted by phone for nearly 10 years, attended weekend workshops, and learned how to “be a man.”

Aaron interrupts himself to eye a woman in shorts jogging by. “Sometimes there are very good-looking women at this boardwalk,” he says. “Especially when they’re not bundled up.” He remembers when he started noticing women’s bodies, a few years into his therapy. “The first thing I noticed was their legs. The curve of their legs.” He’s dated women, had sex with them even, although “I was pretty awkward,” he says. “It just didn’t work.” Aaron has a theory about this: “I never used my body in a sexual way. I think the men who actually act it out have a greater success in terms of being sexual with women than the men who didn’t act it out.” Not surprisingly, he’s never had a long-term relationship, and he’s pessimistic about his prospects. “I can’t make that jump from having this attraction to doing something about it.” But, he adds, it’s wrong to think “if you don’t make it with women, then you haven’t changed.” The important thing is that “now I like myself. I’m not emotionally shut down. I’m comfortable in my own body. I don’t have to be drawn to men anymore. I’m content at this point to lead an asexual life, which is what I’ve done for most of my life anyway.” He adds, “I’m a very detached person.”

It’s raining a little now. We stop walking so I can tuck the microphone under the flap of Aaron’s shirt pocket, and I feel him recoil as I fiddle with his button. I’m remembering his little cubicle of an apartment, its unlived-in feel, and thinking that he may be the sort of guy who just doesn’t like anyone getting too close, but it’s also possible that therapy has taught him to submerge his desire so deep that he’s lost his motive for intimacy.

That’s the usual interpretation of reparative therapy—that to the extent that it does anything, it leads people to repress rather than change their natural inclinations, that its claims to change sexual orientation are an outright fraud perpetrated by the religious right on people who have internalized the homophobia of American society, personalized the political in such a way as to reject their own sexuality and stunt their love lives. But Aaron scoffs at these notions, insisting that his wish to go straight had nothing to do with right-wing religion or politics—he’s a nonobservant Jew and a lifelong Democrat who volunteered for George McGovern, has a career in public service, and thinks George Bush is a war criminal. It wasn’t a matter of ignorance—he has an advanced degree—and it really wasn’t a psychopathological thing—he rejects the idea that he’s ever suffered from internalized homophobia. He just didn’t want to be gay, and, like millions of Americans dissatisfied with their lives, he sought professional help and reinvented himself.

Self-reconstruction is what people in my profession (I am a practicing psychotherapist) specialize in, but when it comes to someone like Aaron, most of us draw the line. All the major psychotherapy guilds have barred their members from researching or practicing reparative therapy on the grounds that it is inherently unethical to treat something that is not a disease, that it contributes to oppression by pathologizing homosexuality, and that it is dangerous to patients whose self-esteem can only suffer when they try to change something about themselves that they can’t (and shouldn’t have to) change. Aaron knows this, of course, which is why he’s at great pains to prove he’s not pulling a Ted Haggard. For if he’s not a poseur, then he is a walking challenge to the political and scientific consensus that has emerged over the last century and a half: that sexual orientation is inborn and immutable, that efforts to change it are bound to fail, and that discrimination against gay people is therefore unjust.

But as crucial as this consensus has been to the struggle for gay rights, it may not be as sound as some might wish. While scientists have found intriguing biological differences between gay and straight people, the evidence so far stops well short of proving that we are born with a sexual orientation that we will have for life. Even more important, some research shows that sexual orientation is more fluid than we have come to think, that people, especially women, can and do move across customary sexual orientation boundaries, that there are ex-straights as well as ex-gays. Much of this research has stayed below the radar of the culture warriors, but reparative therapists are hoping to use it to enter the scientific mainstream and advocate for what they call the right of self-determination in matters of sexual orientation. If they are successful, gay activists may soon find themselves scrambling to make sense of a new scientific and political landscape.

In 1838, a 20-year-old Hungarian killed himself and left a suicide note for Karl Benkert, a 14-year-old bookseller’s apprentice in Budapest whom he had befriended. In it he explained that he had been cleaned out by a blackmailer who was now threatening to expose his homosexuality, and that he couldn’t face either the shame or the potential legal trouble that would follow. Benkert, who eventually became a writer, moved to Vienna, and changed his name to Karoly Maria Kertbeny, later said that the tragedy left him with “an instinctive drive to take issue with every injustice.” And in 1869, a particularly resonant injustice occurred: A penal code proposed for Prussia included an anti-sodomy law much like the one that had given his friend’s extortionist his leverage. Kertbeny published a pamphlet in protest, writing that the state’s attempt to control consensual sex between men was a violation of the fundamental rights of man. Nature, he argued, had divided the human race into four sexual types: “monosexuals,” who masturbated, “heterogenits,” who had sex with animals, “heterosexuals,” who coupled with the opposite sex, and “homosexuals,” who preferred people of the same sex. Kertbeny couldn’t have known that of all his literary output, these latter two words would be his only lasting legacy. But while homosexual conduct had occurred throughout history, the idea that it reflected fundamental differences between people, that gay people were a sexual subspecies, was a new one.

Kertbeny wasn’t alone in creating a sexual taxonomy. Another anti-sodomy-law opponent, lawyer Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, proposed that homosexual men, or “Uranians,” as he called them (and he openly considered himself a Uranian, while Kertbeny was coy about his preferences), were actually a third sex, their attraction to other men a manifestation of the female soul residing in their male bodies. Whatever the theoretical differences between Ulrichs and Kertbeny, they agreed on one crucial point: that sexual behavior was the expression of an identity into which we were born, a natural variation of the human. In keeping with the post-Enlightenment notion that we are morally culpable only for what we are free to choose, homosexuals were not to be condemned or restricted by the state. Indeed, this was Kertbeny and Ulrichs’ purpose: Sexual orientation, as we have come to call this biological essence, was invented in order to secure freedom for gay people.

But replacing morality with biology, and the scrutiny of church and state with the observations of science, invited a different kind of condemnation. By the end of the 19th century, homosexuality was increasingly the province of psychiatrists like Magnus Hirschfeld, a gay Jewish Berliner. Hirschfeld was an outspoken opponent of anti-sodomy laws and championed tolerance of gay people, but he also believed that homosexuality was a pathological state, a congenital deformity of the brain that may have been the result of a parental “degeneracy” that nature intended to eliminate by making the defective population unlikely to reproduce. Even Sigmund Freud, who thought people were “polymorphously perverse” by nature and urged tolerance for homosexuality, believed heterosexuality was essential to maturity and psychological health.

Freud was pessimistic that homosexuality could be treated, but doctors abhor an illness without a cure, and the 20th century saw therapists inflict the best of modern psychiatric practice on gay people, which included, in addition to interminable psychoanalysis and unproven medications, treatments that used electric shock to associate pain with same-sex attraction. These therapies were largely unsuccessful, and, particularly after the Stonewall riots of 1969—the clash between police and gays that initiated the modern gay rights movement—patients and psychiatrists alike started questioning whether homosexuality should be considered a mental illness at all. Gay activists, some of them psychiatrists, disrupted the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association for three years in a row, until in 1973 a deal was brokered. The apa would delete homosexuality from its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (dsm) immediately, and furthermore it would add a new disease: sexual orientation disorder, in which a patient can’t accept his or her sexual identity. The culprit in sod was an oppressive society, and the cure for sod was to help the gay patient overcome oppression and accept who he or she really was. (sod has since been removed from the dsm.)

The apa cited various scientific papers in making its decision, but many members were convinced that the move was a dangerous corruption of science by politics. “If groups of people march and raise enough hell, they can change anything in time,” one psychiatrist worried. “Will schizophrenia be next?” And their impression was confirmed when the final decision was made not in a laboratory but at the ballot box, where the membership voted by a six-point margin to authorize the apa to delete the diagnosis of homosexuality. It may be the first time in history that a disease was eliminated by the stroke of a pen. It was certainly the first time that psychiatrists determined that the cause of a mental illness was an intolerant society. And it was a crucial moment for gay people, at once getting the psychiatrists out of their bedrooms and giving the weight of science to Kertbeny and Ulrichs’ claim that homosexuality was an identity, like race or national origin, that deserved protection.

three decades later, at least one group is still raising hell about the deletion: the National Association for the Research and Therapy of Homosexuality (narth), an organization founded by Charles Socarides, a psychiatrist who led the opposition to the 1973 apa vote. “They will wipe the floor with us,” Socarides (who died in 2005) once said, “but we will wear our wounds as badges of courage,” and at narth‘s November 2006 national meeting in Orlando, Socarides’ firebrand rhetoric is still in the air. You hear it when Joe and Marian Allen take to the lectern to tell us how God has called them to “give testimony” about their gay son who was murdered by his lover, a tragedy that they manage to twist into a cautionary tale about what happens when a “struggler” is told by a “well-meaning therapist” that he was “born gay” and can’t change it. Or when a minion of James Dobson’s Focus on the Family cheerfully explains the Gay Agenda to me: “It’s doing whatever you want, whenever you want, with whoever you want, wherever you want.”

“Well, just for the sake of argument,” I ask, “what’s wrong with that?”

“I’m sure the people who follow that agenda believe what they believe, but they don’t realize that they’re pawns in a great cosmic battle, that they are perpetrating a lie.”

“Pawns of?…”

“Satan,” he informs me, “is the author of lies, chaos, and confusion.”

But the men of narth (nearly all the 75 attendees are white men) aren’t spewing nearly as much hellfire and brimstone as I expected. They do seem to hug a lot—many reparative therapists are ex-gay themselves, and, someone explains, part of being ex-gay is learning to be same-sex affectionate without being same-sex sexual—and maybe some of those hugs last a little too long, but it’s mostly like every other convention: bad coffee, worse Danish, dry-as-dust lectures. narth‘s president-elect, A. Dean Byrd, a psychologist and professor at University of Utah Medical School, methodically lays out his case that sexual orientation is malleable in his daylong seminar on how to treat unwanted same-sex attraction.

If narth‘s strategy is to seek a place at the table by demonstrating its scientific seriousness, Byrd’s modulated approach, tedious as it may be, is just what the doctor ordered. Sometimes he’s puckish—as when he says, “When it comes to homosexuality, I’m pro-choice”—a comment sure to get a rise out of a crowd well versed in the other moral disaster of 1973—and sometimes glib (“the proper answer to the nature/nurture question is yes”), but mostly he’s just workmanlike as he reviews the research—much of it, he is delighted to point out, conducted by the “activists themselves.” He cites a study from Denmark—the first place that legalized civil unions and perhaps, he says, the most gay-friendly place in the world—in which gay people turned out to have mental illness at a higher rate than straights, which proves, he says, that an intolerant society is not the culprit when gay people suffer. He describes studies that show that the identical twin brother of a gay man has only a 50 percent chance of being gay himself, which may be twice the rate among fraternal twins, but still, he argues, far from the 100 percent you would expect if sexual orientation is purely genetic. He even shows us video of one of his treatment sessions, and gives a plausible-sounding assessment of the prospects for patients of reparative therapists—that one-third of them will become heterosexual, one-third will remain gay, and one-third will move a few notches along the Kinsey scale, enough to leave the lifestyle and limit their unwanted feelings and behavior.

Byrd, like everyone else here, is very excited about an article that appeared in Archives of Sexual Behavior in 2003. It was a small study—200 subjects—but it concluded that gay people could indeed change their sexual orientation, that the change was not merely religiously motivated repression or politically motivated bluster but rather some fundamental shift in desire. The researcher concluded that even the people who showed little benefit from reparative therapy didn’t seem to be harmed by it, and that much more research needed to be done. The study was full of caveats and received withering criticism from scientists who claimed that it relied on a skewed sample—mostly people handpicked by reparative therapists like Byrd—but it had passed peer review, and, even more importantly, it had been conducted by none other than Robert Spitzer, the same psychiatrist who had brokered the deal that deleted homosexuality from the dsm.

Spitzer also called for an end to the ban on research into reparative therapy, and one psychologist who has taken him up on that call is welcomed in Orlando like a conquering hero. Elan Karten is an unassuming young man who wears a yarmulke and recently got a doctorate from Fordham after writing a dissertation on ex-gay men. Karten only got the go-ahead for his study by positioning it as an inquiry into the type of people who seek reparative therapy rather than as an exploration of its efficacy. He did manage to sneak in some of that research as well, and reached conclusions similar to Spitzer’s—though peer reviewers objecting that it revives the notion that homosexuality is a mental illness have thus far prevented Karten, an academic unknown, from publishing his work.

By Saturday morning, gay activists have begun to gather outside the hotel to protest narth. We are instructed not to respond to them (“Sing a hymn or pray instead”) as they put on duck outfits, hoist their signs (Stop Ducking the Truth; narth Is Goofy), make quacking noises, and yell “Shame!” in our general direction. Byrd looks out the door, shakes his head, and laughs when a man behind him says, “Quack, quack? They’re the queer ducks.”

I wait until the foyer is empty before I head out to talk to Wayne Besen, a tall man in a polo shirt, who is pulling the props and costumes out of his car trunk. He runs Truth Wins Out, an organization devoted to debunking the research of the ex-gay movement. He minces no words about Spitzer’s research—”one of the most poorly constructed studies in the history of science, a travesty”—and he calls reparative therapy “intelligent design for gay people.” Besen thinks the stakes of the scientific battle are impossible to overstate. “Americans are not cruel. If they think that being gay is inborn and can’t be changed, they are going to be very sympathetic to full equality for gay people,” he says. “We win this argument, the gay rights struggle would be done.”

Besen is sure that science is on the verge of giving gay people their slam dunk. After all, he says, study after study shows that homosexuality is biological in origin. In the last 15 years, researchers have discovered differences in brain anatomy between gay and straight men—and found that the 6 percent of rams that have sex exclusively with other rams (just one of hundreds of species in which homosexual behavior has been observed) have a similar neuroanatomical difference; identified a gene sequence on the X chromosome that is common to many gay men; traced genealogies to show that homosexuality runs in families, on the maternal side; proved that a man’s likelihood of being gay increases with the number of older brothers he has, which scientists attribute to changes in intrauterine chemistry; and learned how to use magnetic resonance imaging to detect sexual orientation by watching the brain’s response to pornography. Findings in the field of anthropometrics have yielded intriguing results: Gay men’s index fingers, for instance, are more likely than straight men’s to be equal in length to their ring fingers; gay men have larger penises than straight men. These findings all seem to support Besen’s contention that being gay is essentially biological and should remain beyond the reach of law, morals, or medicine.

But some activists are more reluctant than Besen to rely on this line of reasoning. “One thing I find troubling within the gay community is a lot of people feel if they can make that claim strongly enough that’s going to give them equal rights,” Sean Cahill, former director of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute, told me. “But I don’t think it really matters,” he says, pointing out that believing that sexual orientation is biological doesn’t cause one to support gay rights. Indeed, many social scientists think that the beliefs are merely correlated, that people who hold one tend to hold the other.

Some gay rights lawyers point out that whatever biology’s role in sexual orientation, it should not be legally paramount. The Supreme Court has ruled that the immutability of a group’s identifying characteristics is one of the criteria that entitle it to heightened protection from discrimination (and some cases establishing gay rights were decided in part on those grounds), but, according to Suzanne Goldberg, director of the Sexuality and Gender Law Clinic at Columbia Law School, there’s a far more fundamental reason for courts to protect gay people. “Sexual orientation does not bear on a person’s ability to contribute to society,” she notes. “We don’t need the science to make that point.” Jon Davidson, legal director of Lambda Legal, agrees, adding that if courts are going to ask about immutability, they shouldn’t focus on biology. Instead they should focus on how sexual orientation is so deeply woven into a person’s identity that it is inseparable from who they are. In this respect, Davidson says, sexual orientation is like another core aspect of identity that is clearly not biological in origin: religion. “It doesn’t matter whether you were born that way, it came later, or you chose,” he says. “We don’t think it’s okay to discriminate against people based on their religion. We think people have a right to believe whatever they want. So why do we think that about religion and not about who we love?”

Cahill—who says he doesn’t think he was born gay—points out that even if it is crucial for public support, essentialism has a dark side: the remedicalization of homosexuality, this time as a biological condition that can be treated. Michael Bailey, a Northwestern University psychologist who has conducted some of the key studies of the genetics of sexual orientation, infuriated the gay and lesbian community with a paper arguing that, should prenatal markers of homosexuality be identified, parents ought to have the right to abort potentially gay fetuses. “It’s reminiscent of eugenicist theories,” Cahill tells me. “If it’s seen as an undesirable trait, it could lead in some creepy directions.” These could include not only abortion, but also gene therapy or modulating uterine hormone levels to prevent the birth of a gay child.

Psychology professor Lisa Diamond may have the best reason of all for activists to shy away from arguing that homosexuality is inborn and immutable: It’s not exactly true. She doesn’t dispute the findings that show a biological role in sexual orientation, but she thinks far too much is made of them. “The notion that if something is biological, it is fixed—no biologist on the planet would make that sort of assumption,” she told me from her office at the University of Utah. Not only that, she says, but the research—which is conducted almost exclusively on men—hinges on a very narrow definition of sexual orientation: “It’s what makes your dick go up. I think most women would disagree with that definition,” she says, not only because it obviously excludes them, but because sexual orientation is much more complex than observable aspects of sexuality. “An erection is an erection,” she says, “but we have almost no information about what is actually going on in terms of the subjective experience of desire.”

Diamond has spent the last 12 years doing her part to fill in this gap by following a group of 79 women who originally described themselves as nonheterosexual, and she’s found that sexual orientation is much more fluid than activists like Besen believe. “Contrary to this notion that gay people struggle with their identity in childhood and early adolescence, then come out and ride off into the sunset,” she says, “the more time goes on, the more variability comes out. Women change their identities and find their attractions changing.” In the first year of her study, 43 percent of her subjects identified themselves as lesbian, 30 percent as bisexual, and 27 percent as unlabeled. By year 10, those percentages had changed significantly: 30 percent said they were lesbian, 29 percent said they were bisexual, 22 percent wouldn’t label themselves, and 7 percent said they were now straight (the remaining 12 percent had left the study). Across the entire group, Diamond found that only 58 percent of her subjects’ sexual partners were women; in year eight, even the women who identified as lesbians reported that between 10 and 20 percent of their sexual partners were men. Diamond concludes that the categorization of women into gay, straight, and bisexual misses an important fact: that they move back and forth among these categories, and that the fluidity that allows them to do so is as crucial a variable in sexual development as their orientation.

Diamond cautions that it’s important not to confuse plasticity—the capacity for sexual orientation to change—with choice—the ability to change it at will. “Trying to change your attractions doesn’t work very well, but you can change the structure of your social life, and that might lead to changes in the feelings you experience.” This is a time-honored way of handling unwanted sexual feelings, she points out. “Jane Austen made a career out of this: People fall in love with a person of the wrong social class. What do you do? You get yourself out of those situations.” For the women in Diamond’s study who tell her, “‘I hate straight society, I don’t want to be straight,'” Austen’s solution is an effective treatment for unwanted other-sex attraction. “If you’re around women all the time and you are never around men, you are probably going to be more attracted to women,” she says. Such women sometimes end up falling in love with women, and their sexual feelings follow. And it can work the other way, Diamond says: Women who identify themselves as gay or bisexual sometimes find themselves, to their own surprise, in love with men with whom they then become sexual partners. Indeed, she says, “love has no sexual orientation.”

Which isn’t all that different from what they say at narth—that people like Aaron who hate the gay lifestyle and don’t want to be gay should leave the gay bars, do regular guy things with men, and put themselves in the company of women for romance. And indeed the narthites know all about Diamond’s work. “We know that straight people become gays and lesbians,” narth‘s outgoing president Joseph Nicolosi told the group gathered in Orlando. “So it seems totally reasonable that some gay and lesbian people would become straight. The issue is whether therapy changes sexual orientation. People grow and change as a result of life experiences, especially personal relationships. Why then can’t the experience of therapy and the relationship with the therapist also effect change?” Diamond calls this interpretation a “misuse” of her research—”the fluidity I’ve observed does not mean that reparative therapy works”—but what is really being misused, she says, is science. “We live in a culture where people disagree vehemently about whether or not sexual minorities deserve equal rights,” she told me. “People cling to this idea that science can provide the answers, and I don’t think it can. I think in some ways it’s dangerous for the lesbian and gay community to use biology as a proxy for that debate.”

aaron doesn’t put it this way, but he thinks of himself as a member of a sexual minority—not forced into the closet by an oppressive society, but living under the restrictive view that sexual orientation is a biological category, something we are born with and that is impossible to change. When I tell him about some of what I saw at narth—like when Nicolosi, recalling one of his antagonists at the apa convention, said, “I knew that she was a lesbian—I don’t know why; she was wearing a muscle shirt”—Aaron doesn’t defend the organization. He knows that narth doesn’t like gay people much (he’s attended one of their meetings). But he’s more concerned with a different kind of intolerance. “Not all homosexual men want to lead a gay lifestyle. Gay activists shouldn’t be threatened by that. I mean, here I am, as a liberal, telling gay people to accept diversity.”

narth spares no opportunity to claim that it is a victim of political correctness, silenced by a science that gay activists hijacked in 1973 and have exploited ever since. It’s a page right out of James Dobson’s playbook, but narth is right on at least one count: The complexity of sexual orientation surpasses the certainties of biology. To the extent that the struggle for gay rights rests on a scientific foundation, narth‘s strategy is bound to pay off. Gay activists will then be left to build on other sources of public sympathy, none of which has the appeal of science. After all, if sexual identity is more like religion than race, a matter of affiliation rather than birth, fluid rather than fixed, then finding a different basis for popular support—as well as for legislative and judicial protection—means confronting directly something Americans are perpetually confused about: the nature and boundaries of pleasure.

narth is perfectly positioned to exploit this confusion by arguing that sexual orientation can be influenced by environmental conditions, and that certain courses are less healthy than others. That’s how narthites justify their opposition to extending marriage and adoption rights to gay people: not because they abhor homosexuality, but because a gay-friendly world is one in which it is hard for gay people to recognize that they are suffering from a medical illness.

Of course, in deploying medical language to serve its strategic interests, narth is only following the lead of Kertbeny and Hirschfeld, the original gay activists, and their modern counterparts who, despite minimizing the importance of biology, resort to scientific rhetoric when it suits their purposes. “People can’t try to shut down a part of who they are,” says Sean Cahill. “I don’t think it’s healthy for people to change how their body and mind and heart work.”

But medicine, which is what we rely on to tell us what is “healthy,” will always seek to change the way people’s bodies and minds and hearts work; yesterday’s immutable state of nature is tomorrow’s disease to be cured. Medical science can only take its cues from the society whose curiosities it satisfies and whose confusions it investigates. It can never do the heavy political lifting required to tell us whether one way of living our lives is better than another. This is exactly why Kertbeny originated the notion of a biologically based sexual orientation, and, to the extent that society is more tolerant of homosexuality now than it was 150 years ago, that idea has been a success. But the ex-gay movement may be the signal that this invention has begun to outlive its usefulness, that sexuality, profoundly mysterious and irrational, will not be contained by our categories, that it is time to find reasons other than medical science to insist that people ought to be able to love whom they love.