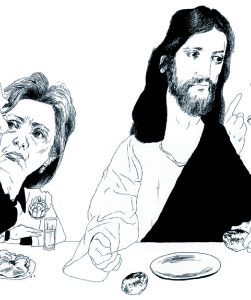

Illustration by: Andy Friedman

It was an elegant example of the Clinton style, a rhetorical maneuver subtle, bold, and banal all at once. During a Democratic candidate forum in June, hosted by the liberal evangelical group Sojourners, Hillary Clinton fielded a softball query about Bill’s infidelity: How had her faith gotten her through the Lewinsky scandal?

After a glancing shot at Republican “pharisees,” Clinton explained that, of course, her “very serious” grounding in faith had helped her weather the affair. But she had also relied on the “extended faith family” that came to her aid, “people whom I knew who were literally praying for me in prayer chains, who were prayer warriors for me.”

Such references to spiritual warfare—prayer as battle against Satan, evil, and sin—might seem like heavy evangelical rhetoric for the senator from New York, but they went over well with the Sojourners audience, as did her call to “inject faith into policy.” It was language that recalled Clinton’s Jesus moment a year earlier, when she’d summoned the Bible to decry a Republican anti-immigrant initiative that she said would “criminalize the good Samaritan…and even Jesus himself.” Liberal Christians crowed (“Hillary Clinton Shows the Way Democrats Can Use the Bible,” declared a blogger at TPMCafe) while conservative pundits cried foul, accusing Clinton of scoring points with a faith not really her own.

In fact, Clinton’s God talk is more complicated—and more deeply rooted—than either fans or foes would have it, a revelation not just of her determination to out-Jesus the gop, but of the powerful religious strand in her own politics. Over the past year, we’ve interviewed dozens of Clinton’s friends, mentors, and pastors about her faith, her politics, and how each shapes the other. And while media reports tend to characterize Clinton’s subtle recalibration of tone and style as part of the Democrats’ broader move to recapture the terrain of “moral values,” those who know her say there’s far more to it than that.

Through all of her years in Washington, Clinton has been an active participant in conservative Bible study and prayer circles that are part of a secretive Capitol Hill group known as the Fellowship. Her collaborations with right-wingers such as Senator Sam Brownback (R-Kan.) and former Senator Rick Santorum (R-Pa.) grow in part from that connection. “A lot of evangelicals would see that as just cynical exploitation,” says the Reverend Rob Schenck, a former leader of the militant anti-abortion group Operation Rescue who now ministers to decision makers in Washington. “I don’t….there is a real good that is infected in people when they are around Jesus talk, and open Bibles, and prayer.”

Clinton’s faith is grounded in the Methodist beliefs she grew up with in Park Ridge, Illinois, a conservative Chicago suburb where she was active in her church’s altar guild, Sunday school, and youth group. It was there, in 1961, that she met the Reverend Don Jones, a 30-year-old youth pastor; Jones, a friend of Clinton’s to this day, told us he knows “more about Hillary Clinton’s faith than anybody outside her family.”

Because Jones introduced Clinton and her teenage peers to the civil rights movement and modern poetry and art, Clinton biographers often cast him as a proto-’60s liberal who sowed seeds of radicalism throughout Park Ridge. Jones, though, describes his theology as neoorthodox, guided by the belief that social change should come about slowly and without radical action. It emerged, he says, as a third way, a reaction against both separatist fundamentalism and the New Deal’s labor-based liberalism.

Under Jones’ mentorship, Clinton learned about Reinhold Niebuhr and Paul Tillich—thinkers whom liberals consider their own, but whom young Hillary Rodham encountered as theological conservatives. The Niebuhr she studied was a cold warrior, dismissive of the progressive politics of his earlier writing. “He’d thought that once we were unionized, the kingdom of God would be ushered in,” Jones explains. “But the effect of those two world wars and the violence that they produced shook his faith in liberal theology. He came to believe that the achievement of justice meant a clear understanding of the limitations of the human condition.” Tillich, whose sermon on grace Clinton turned to during the Lewinsky scandal, today enjoys a following among conservatives for revising the social gospel—the notion that Christians are to improve humanity’s lot here on earth by fighting poverty, inequality, and exploitation—to emphasize individual redemption instead of activism.

Niebuhr and Tillich’s combination of aggressiveness in foreign affairs and limited domestic ambition naturally led Clinton toward the gop. She was a Goldwater Girl who, under the tutelage of her high school history teacher Paul Carlson (whom Jones describes as “to the right of the John Birchers”), attended biweekly anticommunist meetings and later served as president of Wellesley’s Young Republicans chapter. Out of step with the era’s radicalism, Clinton wrote Jones from college, lamenting that her fellow students didn’t believe that one could be “a mind conservative and a heart liberal.” To Jones, this question indicated that Clinton shared Niebuhr’s notion of Christians needing to have “a dark enough view of life that they can be realistic about what’s possible.”

Two decades later, while Bill was campaigning for president, Clinton picked up that theme once more, displaying a theological depth that conservative believers could appreciate. In an interview with the United Methodist Reporter, she expressed regret that her church had focused too much on social gospel concerns in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, “to the exclusion of personal faith and growth.” The spirit, believe theological conservatives, matters more than the flesh. Clinton added that she was happy to see her liberal denomination becoming more salvation centered in the ’90s.

When Clinton first came to Washington in 1993, one of her first steps was to join a Bible study group. For the next eight years, she regularly met with a Christian “cell” whose members included Susan Baker, wife of Bush consigliere James Baker; Joanne Kemp, wife of conservative icon Jack Kemp; Eileen Bakke, wife of Dennis Bakke, a leader in the anti-union Christian management movement; and Grace Nelson, the wife of Senator Bill Nelson, a conservative Florida Democrat.

Clinton’s prayer group was part of the Fellowship (or “the Family”), a network of sex-segregated cells of political, business, and military leaders dedicated to “spiritual war” on behalf of Christ, many of them recruited at the Fellowship’s only public event, the annual National Prayer Breakfast. (Aside from the breakfast, the group has “made a fetish of being invisible,” former Republican Senator William Armstrong has said.) The Fellowship believes that the elite win power by the will of God, who uses them for his purposes. Its mission is to help the powerful understand their role in God’s plan.

Clinton declined our requests for an interview about her faith, but in Living History, she describes her first encounter with Fellowship leader Doug Coe at a 1993 lunch with her prayer cell at the Cedars, the Fellowship’s majestic estate on the Potomac. Coe, she writes, “is a unique presence in Washington: a genuinely loving spiritual mentor and guide to anyone, regardless of party or faith, who wants to deepen his or her relationship with God.”

The Fellowship’s ideas are essentially a blend of Calvinism and Norman Vincent Peale, the 1960s preacher of positive thinking. It’s a cheery faith in the “elect” chosen by a single voter—God—and a devotion to Romans 13:1: “Let every soul be subject unto the higher powers….The powers that be are ordained of God.” Or, as Coe has put it, “we work with power where we can, build new power where we can’t.”

When Time put together a list of the nation’s 25 most powerful evangelicals in 2005, the heading for Coe’s entry was “The Stealth Persuader.” “You know what I think of when I think of Doug Coe?” the Reverend Schenck (a Coe admirer) asked us. “I think literally of the guy in the smoky back room that you can’t even see his face. He sits in the corner, and you see the cigar, and you see the flame, and you hear his voice—but you never see his face. He’s that shadowy figure.”

Coe has been an intimate of every president since Ford, but he rarely imposes on chief executives, who see him as a slightly mystical but apolitical figure. Rather, Coe uses his access to the Oval Office as currency with lesser leaders. “If Doug Coe can get you some face time with the President of the United States,” one official told the author of a Princeton study of the National Prayer Breakfast last year, “then you will take his call and seek his friendship. That’s power.”

“If you’re going to do religion in public life,” concurs Schenck, a Jewish convert to fundamentalist Christianity who’s retained his sense of irony, Coe’s friendship is a kind of “kosher…seal of approval.”

Coe’s friends include former Attorney General John Ashcroft, Reaganite Edwin Meese III, and ultraconservative Rep. Joe Pitts (R-Pa.). Under Coe’s guidance, Meese has hosted weekly prayer breakfasts for politicians, businesspeople, and diplomats, and Pitts rose from obscurity to head the House Values Action Team, an off-the-record network of religious right groups and members of Congress created by Tom DeLay. The corresponding Senate Values Action Team is guided by another Coe protégé, Brownback, who also claims to have recruited King Abdullah of Jordan into a regular study of Jesus’ teachings.

The Fellowship’s long-term goal is “a leadership led by God—leaders of all levels of society who direct projects as they are led by the spirit.” According to the Fellowship’s archives, the spirit has in the past led its members in Congress to increase U.S. support for the Duvalier regime in Haiti and the Park dictatorship in South Korea. The Fellowship’s God-led men have also included General Suharto of Indonesia; Honduran general and death squad organizer Gustavo Alvarez Martinez; a Deutsche Bank official disgraced by financial ties to Hitler; and dictator Siad Barre of Somalia, plus a list of other generals and dictators. Clinton, says Schenck, has become a regular visitor to Coe’s Arlington, Virginia, headquarters, a former convent where Coe provides members of Congress with sex-segregated housing and spiritual guidance.

We contacted all of Clinton’s Fellowship cell mates, but only one agreed to speak—though she stressed that there’s much she’s not “at liberty” to reveal. Grace Nelson used to be the organizer of the Florida Governor’s Prayer Breakfast, which makes her a piety broker in Florida politics—she would decide who could share the head table with Jeb Bush. Clinton’s prayer cell was tight-knit, according to Nelson, who recalled that one of her conservative prayer partners was at first loath to pray for the first lady, but learned to “love Hillary as much as any of us love Hillary.” Cells like these, Nelson added, exist in “parliaments all over the world,” with all welcome so long as they submit to “the person of Jesus” as the source of their power.

Throughout her time at the White House, Clinton writes in Living History, she took solace from “daily scriptures” sent to her by her Fellowship prayer cell, along with Coe’s assurances that she was right where God wanted her. (Clinton’s sense of divine guidance has been noted by others: Bishop Richard Wilke, who presided over the United Methodist Church of Arkansas during her years in Little Rock, told us, “If I asked Hillary, ‘What does the Lord want you to do?’ she would say, ‘I think I’m called by the Lord to be in public service at whatever level he wants me.'”)

Coe counsels that Fellowship cells shouldn’t engage in direct evangelical activism, but rather allow Christian causes to benefit from the bonds that develop within the cells. Former Nixon counsel Chuck Colson provides a rare illustration of the process in his 1976 Watergate memoir, Born Again. Facing prosecution in 1973, Colson allowed Coe to ensconce him in a Fellowship cell with a Nixon foe, Senator Harold Hughes. Hughes became the Nixon hatchet man’s staunchest defender, voting in favor of a possible pardon for Colson and later supporting Colson as he built Prison Fellowship, now one of the most powerful organizations of the Christian right.

That’s how it works: The Fellowship isn’t out to turn liberals into conservatives; rather, it convinces politicians they can transcend left and right with an ecumenical faith that rises above politics. Only the faith is always evangelical, and the politics always move rightward.

This is in line with the Christian right’s long-term strategy. Francis Schaeffer, late guru of the movement, coined the term “cobelligerency” to describe the alliances evangelicals must forge with conservative Catholics. Colson, his most influential disciple, has refined the concept of cobelligerency to deal with less-than-pure politicians. In this application, conservatives sit pretty and wait for liberals looking for common ground to come to them. Clinton, Colson told us, “has a lot of history” to overcome, but he sees her making the right moves.

These days, Clinton has graduated from the political wives’ group into what may be Coe’s most elite cell, the weekly Senate Prayer Breakfast. Though weighted Republican, the breakfast—regularly attended by about 40 members—is a bipartisan opportunity for politicians to burnish their reputations, giving Clinton the chance to profess her faith with men such as Brownback as well as the twin terrors of Oklahoma, James Inhofe and Tom Coburn, and, until recently, former Senator George Allen (R-Va.). Democrats in the group include Arkansas Senator Mark Pryor, who told us that the separation of church and state has gone too far; Joe Lieberman (I-Conn.) is also a regular.

Unlikely partnerships have become a Clinton trademark. Some are symbolic, such as her support for a ban on flag burning with Senator Bob Bennett (R-Utah) and funding for research on the dangers of video games with Brownback and Santorum. But Clinton has also joined the gop on legislation that redefines social justice issues in terms of conservative morality, such as an anti-human-trafficking law that withheld funding from groups working on the sex trade if they didn’t condemn prostitution in the proper terms. With Santorum, Clinton co-sponsored the Workplace Religious Freedom Act; she didn’t back off even after Republican senators such as Pennsylvania’s Arlen Specter pulled their names from the bill citing concerns that the measure would protect those refusing to perform key aspects of their jobs—say, pharmacists who won’t fill birth control prescriptions, or police officers who won’t guard abortion clinics.

Clinton has championed federal funding of faith-based social services, which she embraced years before George W. Bush did; Marci Hamilton, author of God vs. the Gavel, says that the Clintons’ approach to faith-based initiatives “set the stage for Bush.” Clinton has also long supported the Defense of Marriage Act, a measure that has become a purity test for any candidate wishing to avoid war with the Christian right.

Liberal rabbi Michael Lerner, whose “politics of meaning” Clinton made famous in a speech early in her White House tenure, sees the senator’s ambivalence as both more and less than calculated opportunism. He believes she has genuine sympathy for liberal causes—rights for women, gays, immigrants—but often will not follow through. “There is something in her that pushes her toward caring about others, as long as there’s no price to pay. But in politics, there is a price to pay.”

In politics, those who pay tribute to the powerful also reap rewards. When Ed Klein’s attack bio, The Truth About Hillary, came out in 2005, some of her most prominent defenders were Christian conservatives, among them Southern Baptist Theological Seminary President Albert Mohler. “Christians,” he declared, “should repudiate this book and determine to take no pleasure in it.”

Senator Brownback understood the temptation. He used to hate Clinton so much, he told us, that the hate hurt. Then came the Clintons’ 1994 National Prayer Breakfast appearance with Mother Teresa, who upbraided the couple for their pro-choice views. Bill made no attempt to conceal his anger, but Hillary took it and smiled. Brownback remembers thinking, “Now, there’s gotta be a great lesson here.” He didn’t know what it was until Clinton got to the Senate and joined him in supporting DeLay’s Day of Reconciliation resolution following the 2000 election, a proposal described by its backers as a call to “pray for our leaders.” Now, Brownback considers Clinton “a beautiful child of the living God.”

Clinton, for her part, turned Mother Teresa’s sucker punch into political opportunity. She met with the nun after the prayer breakfast, visited her orphanage in India, helped her set up another one in Washington (which has since become an apparently inoperative branch of Mother Teresa’s conservative Vatican order, the Missionaries of Charity), and generally built a highly visible friendship with a figure whose moral bona fides also came with an anti-abortion imprimatur that couldn’t but help Clinton on the right.

Of course, no matter how much Clinton speaks of common ground, she doesn’t stand a chance of winning votes among pro-lifers. As Tom McClusky of the Family Research Council, command central for Washington’s Christian right, told us, movement conservatives consider legislation like Clinton’s Putting Prevention First Act, which supports greater access to birth control and sex ed, “just another condom giveaway.”

But the senator’s project isn’t the conversion of her adversaries; it’s tempering their opposition so she can court a new generation of Clinton Republicans, values voters who have grown estranged from the Christian right. And while such crossover conservatives may never agree with her on the old litmus-test issues, there is an important, and broader, common ground—the kind of faith-based politics that, under the right circumstances, will permit majority morality to trump individual rights. The libertarian Cato Institute recently observed that Clinton is “adding the paternalistic agenda of the religious right to her old-fashioned liberal paternalism.” Clinton suggests as much herself in her 1996 book, It Takes a Village, where she writes approvingly of religious groups’ access to schools, lessons in Scripture, and “virtue” making a return to the classroom.

Then, as now, Clinton confounded secularists who recognize public faith only when it comes wrapped in a cornpone accent. Clinton speaks instead the language of nondenominationalism—a sober, eloquent appreciation of “values,” the importance of prayer, and “heart” convictions—which liberals, unfamiliar with the history of evangelical coalition building, mistake for a tidy, apolitical accommodation, a personal separation of church and state. Nor do skeptical voters looking for political opportunism recognize that, when Clinton seeks guidance among prayer partners such as Coe and Brownback, she is not so much triangulating—much as that may have become second nature—as honoring her convictions. In her own way, she is a true believer.