Honors History Class at Mission High School. Photos: Celine Nadeau

“The big bad California STAR Test is in 27 days, everyone!” Mission High School history teacher Robert Roth announces at the beginning of an honors class in March. “The way you are going to feel this is we are going to go through events really quick. But don’t worry, we’ll look at some things more deeply after the test,” Roth explains as 25 juniors trickle in. “I’m hecka bad at these tests,” Marilyn* says out loud; she puts her head down on the desk. Roth walks over to Marilyn and puts his hands on her shoulders. “No, you are not!” he says. “You are not bad at anything that’s important.”

Every spring since 2001, students in 3rd to 11th grades in the US sit down to take standardized tests, which are federally mandated by the No Child Left Behind Act. But how standard can standardized testing really be, when each state decides which basic “standards”—or lessons—to teach, and how to test students’ knowledge of them? In California schools, standardized tests consist of multiple-choice questions only (except for a short written assignment in fourth and seventh grade). Ideally, standards and tests are rigorous. In reality, Mission High teachers believe the quality of the “multiple choice” tests in California is very low, and doesn’t measure the achievement of its diverse student population. But since punishments—including school closures and staff firings—are attached to these test scores, many students and teachers here say they have urgent recommendations for “fixing” what Principal Eric Guthertz calls the “broken scales” of NCLB.

As Roth passes out a preview sheet of the California Standardized Test, Brianna Frank rushes in and takes her seat. “I’m hungry. I’m always hungry,” she says. Diana* finds a red apple in her backpack and gives it to Brianna, who takes two buses from the Bayview/Hunters Point neighborhood each morning to get to school. As students take their seats, Brianna and Diana come up to the front of the class. “How many of you have heard of the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921?” Brianna asks her classmates before she gets started on her presentation. Two hands go up.

A few weeks ago, Roth offered students their choice of research projects. Most of the options were topics that won’t appear in the STAR multiple-choice questions, but Roth believes they make history relevant and interesting to his students. The Tulsa Race Riot jumped out at Brianna right away. Her boyfriend’s grandmother, Edna Tobie, is from Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Tobie was six when the riot happened in 1921. Brianna spent a day at Tobie’s house talking to her and her sons about it. “It was the second-largest African-American community at the time,” she tells the class now. “There were black-owned businesses, a real sense of pride in people, but the local government didn’t want to keep it going like that. So they attacked the community. The federal government didn’t come to defend Tulsa residents from the violence. No justice was served, and some older folks blame it now on young men’s disrespect for the law and the police. Even though it happened a long time ago, there are deep, deep scars in Tulsa. Edna’s sons couldn’t stop talking about it even though they weren’t even alive then.” Brianna’s classmates clap as she takes her seat, a big smile on her face.

“I want to be a social worker,” Brianna tells me after class one day. “Where scars come from is important for me to understand.” She didn’t like history at all in middle school, but seeing why bills like the 14th Amendment got passed, and how long it took to make those words on paper real, fascinates her now. “A lot of people struggled before me so I can be a free black woman. It was very touching to hear,” Brianna reflected after hearing Tobie’s story.

If you spend a day at Mission High, it’s hard to miss Brianna. She walks straight-backed, with a big smile on her face. She looks after people. “Why weren’t you in class yesterday?” she says to two Latino girls while rushing on her way to volunteer for a prom fundraiser. She has her hand up with questions or comments more than anyone else in Roth’s class. “Mr. Roth, what was the Truman Doctrine?” “What’s the Dream Act, again?” “How do you spell Guantanamo?” Roth says Brianna will get a high grade in his honors class, but she tells me she struggles with the standardized tests. “Why do they write them like they’re trying to trick me? Who writes instructions for them?” she wonders.

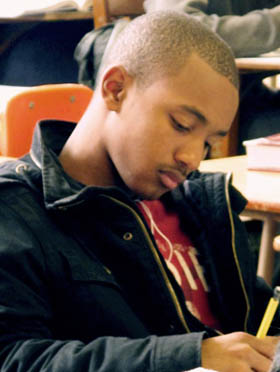

Mission High Junior Marvin JordanA week before the STAR test, Roth was covering the Civil Rights Movement and played “I’ve been to the Mountaintop,” Martin Luther King Jr.’s last speech before his assassination. Most students haven’t seen this speech before, and as the clip ends, there is a heavy silence in the class. During lunch that day, Marvin Jordan comes back to Roth’s class. “I just want to play that speech over and over and over again,” Marvin says. “Even though King knows he will die, he is blossoming. He knows people will continue the fight. Makes you really think about what’s important in life.” He wrote the strongest essay after this documentary, Roth told me recently.

Mission High Junior Marvin JordanA week before the STAR test, Roth was covering the Civil Rights Movement and played “I’ve been to the Mountaintop,” Martin Luther King Jr.’s last speech before his assassination. Most students haven’t seen this speech before, and as the clip ends, there is a heavy silence in the class. During lunch that day, Marvin Jordan comes back to Roth’s class. “I just want to play that speech over and over and over again,” Marvin says. “Even though King knows he will die, he is blossoming. He knows people will continue the fight. Makes you really think about what’s important in life.” He wrote the strongest essay after this documentary, Roth told me recently.

In 2005, when Roth was teaching at Thurgood Marshall High School, a consultant from the California’s Department of Education came in to observe his classes and suggested to him that he concentrate less on writing assignments like these and more on multiple-choice exercises to prepare for the standardized test. “‘After all,” Roth recalls being told, “the test has no writing component.”

“If California is serious about measuring real student achievement, we have to ask students to show what they understood about why an historical event took place, and how that connects to their lives,” Roth argues. He is resisting the pressures to cut out project-based learning like the Tulsa Race Riot or cut out reflections on the civil rights or discuss the implications of the 14th Amendment on immigration today, but there is no denying that the “hammer” of the sanctions is on his mind. Mission High’s test scores have been going up, but that didn’t prevent it from landing in the bottom 5 percent of the 843 “persistently lowest-performing” schools in the nation.

That meant the school qualified for much-needed federal funding through the Race to the Top School Improvement Grant, but it comes with increased scrutiny, and the school lucked out this time around. Since Principal Guthertz just became a principal–after working as vice principal for three years and English teacher for five at Mission High–the district didn’t have to “replace” him as the grant requires under the “transformation” model.

During one recent lunch break, Brianna’s classmates Marilyn and her boyfriend Miguel* linger on in Roth’s class, as students often do. Miguel and Marilyn are undocumented immigrants. They talk to Roth about “Secure Communities,” a controversial law that requires local authorities to report fingerprints of anyone arrested with the federal agencies, which could lead to eventual deportation. Marilyn’s friend, another student at Mission High, was arrested in San Francisco and detained in Washington, DC, for eight months because of this law, she says. “Marilyn was just educating me about this issue yesterday,” Brianna says on her way out of the class. “I had no idea that this issue was such a struggle for her.” Marilyn and Miguel are now gathering petitions to repeal Secure Communities in San Francisco, and they’re talking to students in different schools about their rights. Miguel is excited because a radio reporter said he wants to interview him about the law. “What will you talk about?” Roth asks Miguel. “The 14th Amendment,” he says without a pause, and “the need for due process.”

During one recent lunch break, Brianna’s classmates Marilyn and her boyfriend Miguel* linger on in Roth’s class, as students often do. Miguel and Marilyn are undocumented immigrants. They talk to Roth about “Secure Communities,” a controversial law that requires local authorities to report fingerprints of anyone arrested with the federal agencies, which could lead to eventual deportation. Marilyn’s friend, another student at Mission High, was arrested in San Francisco and detained in Washington, DC, for eight months because of this law, she says. “Marilyn was just educating me about this issue yesterday,” Brianna says on her way out of the class. “I had no idea that this issue was such a struggle for her.” Marilyn and Miguel are now gathering petitions to repeal Secure Communities in San Francisco, and they’re talking to students in different schools about their rights. Miguel is excited because a radio reporter said he wants to interview him about the law. “What will you talk about?” Roth asks Miguel. “The 14th Amendment,” he says without a pause, and “the need for due process.”

Marilyn moved here five years ago from El Salvador to reunite with her mother, who moved here to support her extended seven-member family: “I was raised by my auntie, who got killed by a gang member.” Since Marilyn and her mother were separated for 12 years, they aren’t that close. “We don’t talk much,” Marilyn says. Five months ago, she didn’t raise her hand or say much in class, even though her writing was always good. By the end of school year, she speaks out and has her hand up often. “Mr. Roth always tells me that I need to trust myself and be strong,” she tells me recently. “I don’t have a lot of self-confidence, but I love debating and expressing my opinion.”

A few days earlier, Marilyn took a review test designed by Roth. About half of the test was multiple choice. The other half consisted of short, written responses. Marilyn got a “C” in the multiple-choice section and an “A+” on the written responses. Even though Marilyn has been in the country for five years and can no longer take a modified test for English learners, words like “escalate” or “initiate” on the standardized tests make her nervous, and she gets stuck. In other respects, Roth thinks she does really well: Marilyn can analyze and connect dots. Her critical thinking and problem-solving skills are very strong. Her self-confidence has been growing.”Do we really need kids who can memorize in modern society?” Roth, who has been teaching in inner-city schools his entire 23-year career, asks me on the day we look over Marilyn’s test results. “I think our society needs history students who can think: research, analyze different primary sources, write well, detect biases. The standardized history test doesn’t measure any of these skills.”

By mid-April, the testing pressure was in the air around Mission High hallways. Brianna, Marilyn, Miguel, and Marvin had been working with their “advisory” teachers for months to prepare for the exams. Principal Guthertz performed a cover of “Stand by Me” with new lyrics he wrote about the importance of tests. He also promised to fundraise for a boat party or eat live worms in public if scores go up this year. Last year, the school was promised gourmet lunch served by a famous chef, and when the scores went up, Mission High delivered.

“Listen! One more day before the big bad test, everyone!” Mr. Roth announced on April 8. “All I’m asking you to do is take it seriously. Do it for the school.” “Are they all just multiple choice, again?” Marvin asks. “That’s it,” Roth says, “but it doesn’t show exactly what you know.” “What does it show?” Marvin asks. “Just what you remember. This is not how it will be in college.”

“Listen! One more day before the big bad test, everyone!” Mr. Roth announced on April 8. “All I’m asking you to do is take it seriously. Do it for the school.” “Are they all just multiple choice, again?” Marvin asks. “That’s it,” Roth says, “but it doesn’t show exactly what you know.” “What does it show?” Marvin asks. “Just what you remember. This is not how it will be in college.”

“Let’s do a quick review together.” Students pick their own partners and move seats. “Give me two things about the 14th Amendment!” Roth asks Darrell, as he walks around the class checking on groups. Dozens of students shout out the answers before he has a chance to respond. “What were the Palmer Raids? Who was the first Catholic president? Give me three things about the New Deal?” The back and forth turns into competitive shouting and laughter takes over the classroom. Marvin has his hand in the air permanently. “You are going to nail this test! Don’t let them trick you!”

Once the test is over, the students are circumspect about their experience. “I think I did well on the history test, but they should add more questions on Black and Latino history,” Brianna tells me. Marilyn thinks that teachers from schools like Mission High should help testing companies choose the passages for the English reading part. “All the reading sections for English were so boring! I had to get up several times not to fall asleep,” she tells me while three other students around her chime in and agree. “Our English classes have much better readings,” another student says.

“This is my dream job,” Betty Lee, who has been teaching math for three years at Mission High, tells me a week after the test. But she, too, believes that there is a misguided disconnect between what she thinks students should know and how the state chooses to measure and grade their success. “I teach them the big picture and concepts of mathematics. This is where problem-solving skills come from. The test looks at their procedural fluency. It emphasizes memorization over reasoning skills.” Lee says that most of her students are immigrants, and if they misunderstand one word, it throws the whole question off.

Roth wants to see more writing in the tests, more open-ended questions, and he wants at least some judging to be done by teachers in the district, not just distant bureaucrats who have never met any of his students. Lee agrees and adds, “The instructions should be written in a more accessible language to different cultures, and teachers from diverse backgrounds should be paid to provide feedback when these standards and tests are developed,” Lee offered. “Instead of asking for the date and summary of the Social Security Act, why not give the Act itself and have the student analyze it and compare it to others, which you can still do with bubbles,” Guthertz offered as an example, recently. Since colleges don’t look at these standardized test scores, it’s hard to make them meaningful for students. Some students, like Brianna, feel a deep sense of pride about Mission High and want “to do well” for the school or a teacher. “Some bubble in randomly or draw patterns on the tests,” Roth says.

When teachers and Principal Guthertz talk about these challenges, NCLB and Race to the Top come up often. Sometimes NCLB is associated with George W. Bush, even though it had civil rights groups behind it and was strongly supported by liberal stalwarts like the late Ted Kennedy. Stanford professor Linda Darling-Hammond wrote in The Flat World and Education that the law was a “major breakthrough” for flagging inequalities in education in terms of race and class, and it triggered attention for many historically neglected schools. For the first time, the federal government said that states had to meet the minimum standards for all students, especially students of color and special education students, and not mask their scores with the overall averages, Time‘s education columnist Andrew Rotherham explained. “We moved from really stale conversations with generalities to fairly empirical conversation. The accountability system is not perfect, but the data is much more fine-grained,” he argued.

Ten years after the law was passed, a growing number of advocates now argue that the law has too many brutal unintended consequences and must be reformed. Organizations like the NAACP and the Community Strategy Center claim that failed measurement policies have actually pushed more students of color and low-income students into prisons than colleges. In a recent report (PDF), these groups argue that some schools are “increasing” their test scores by “punishing” failing students through suspensions, expulsions, and school-based arrests. Over 150 organizations have endorsed the report, urging federal policy makers to fix NCLB.

John Burke with the Achievement Assessments Office at San Francisco Unified has some good news. “There is no doubt that the measures need to be broadened, and there is an agreement on the state and national level that assessment systems need to include more writing, expository information, and open-ended questions,” he explained. That’s why last year, California, along with 45 other states, adopted “Common Core” academic standards initiative. The US Department of Education allocated significant funding for two multi-state consortia to create new standardized tests based on the Common Core standards in reading and math. Both consortiums of organizations (PARCC and SMARTER) claim that they plan to involve teachers in designing and scoring the new assessments. Unfortunately for teachers at Mission High, these potentially improved tests won’t hit classrooms until 2015, and won’t affect tests used by Roth in social sciences. For now, teachers are stuck using the same old “broken” scales, while all “punishments” are attached to them. President Obama acknowledged that using current scales, four out of five schools could be labeled as failures, and is lobbying to overhaul NCLB this year.

While most educators, including Principal Guthertz, don’t believe that NCLB should be thrown out completely, all the Mission High teachers I talked to want to see more nuanced, broader measures. They want more local control over “quality” definitions and a more nuanced approach to measuring “success” of a school. The law should be rewritten to include broader measures in calculating “adequate yearly progress” of schools, Guthertz told me. “We need to attach real weight to other measures to supplement data that states and federal government use: grades, attendance and suspension rates, drop out rates, college acceptances, student, parent and teacher satisfaction surveys, Latino and African-American students in Honors and AP classes.” This, Guthertz believes, will help states send a strong message to schools on how these benchmarks should be met: encourage not just higher scores, but also healthy and supportive learning cultures. “We send more African-American students to college than most schools in the district. Our student and parent satisfaction surveys are very high. Why isn’t that considered?” he wonders about the numbers that landed Mission High School on the “lowest-performing schools” list.

“In my middle school, my teacher once told me that I’ll never go to college,” Marilyn tells me in between classes last week. “Then I came here, and Mr. Velez made me feel welcome and connected me to scholarships. Mr. Roth expects more from me than anyone. Why did they put us on that list of worst schools? Why doesn’t my opinion about my school matter?”

*Editors’ Note: This education dispatch is part of an ongoing series reported from Mission High School, where education writer Kristina Rizga is embedded for the year. Names of some students are changed. Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get all of the latest Mission High dispatches.