<a href="http://www.nv.doe.gov/library/photos/photodetails.aspx?ID=1047">Department of Energy</a>

On April 5, 2009, President Barack Obama took the stage before 20,000 people in Prague’s Hradcany Square to offer an ambitious global vision. “Today, I state clearly and with conviction America’s commitment to seek the peace and security of a world without nuclear weapons,” he told the open-air audience in the former Eastern Bloc capital. “To put an end to Cold War thinking, we will reduce the role of nuclear weapons in our national security strategy, and urge others to do the same.”

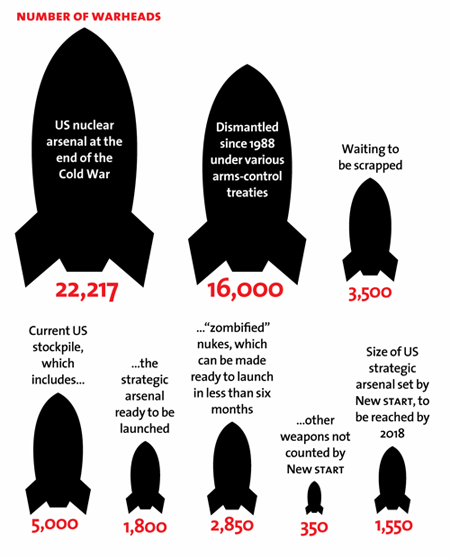

The timing of his bold promise seemed perfect. Russia was ready to whittle down its destructive power; a year later, Obama and President Dmitri Medvedev would sign a treaty limiting both countries to 1,500 active warheads—though still enough to annihilate millions of people, a 50 percent reduction to each nation’s atomic arsenal. Back home, lawmakers on Capitol Hill were scrutinizing the federal budget for unnecessary spending, and nuclear weapons no longer appeared to be off limits.

Even the military brass was moving away from relying upon nuclear deterrence. The Pentagon’s 2010 Nuclear Posture Review (PDF) concluded that “[t]he massive nuclear arsenal we inherited from the Cold War era of bipolar military confrontation is poorly suited to address the challenges posed by suicidal terrorists and unfriendly regimes seeking nuclear weapons.”

But shrinking America’s nuclear arsenal has turned out to be far easier said than done. Despite the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) cuts, federal spending on the atomic stockpile is actually beyond Cold War levels, driven by congressional hawks and powerful nuclear labs eager to “modernize” the arsenal and fund projects that could spark a new arms race.

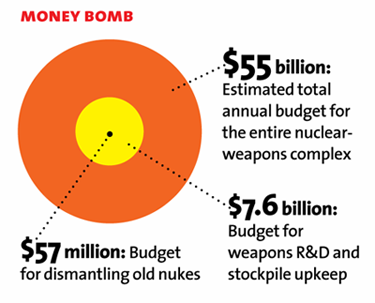

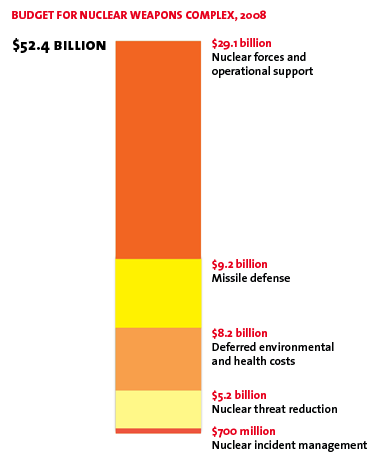

During the Cold War, the United States spent, on average, $35 billion a year on its nuclear weapons complex. Today, it spends an estimated $55 billion. The nuclear weapons budget is spread across the Department of Defense, the Department of Energy, and the Department of Homeland Security, and the government doesn’t publicly disclose how much it spends on its various aspects, from maintaining our nuclear arsenal to defending against other countries’ nukes. Altogether, it spent at least $52.4 billion on nuclear weapons in 2008, the last year anyone attempted to piece together the total cost, according to the Carnegie Endowment for Peace. (And that doesn’t include classified programs.) That was five times the size of the State Department’s budget, seven times the EPA’s, and 14 times what the DOE spent on everything else it does.

So why is America’s nuclear capacity expanding even as it tells the world it plans to forsake its arsenal? A few little-known facts about the nuclear weapons complex provide some answers:

Nuclear secret #1: Old bombs don’t die, they zombify.

The United States currently has 5,113 atomic warheads deployed in silos, bombers, and submarines across the country and the world, ready for use at a moment’s notice. Under the New START treaty, 3,000 of these warheads will be taken out of deployment by 2018. The treaty also mandates deep cuts to both the United States’ and Russia’s nuclear-equipped bombers, submarine launchers, and ICBM silos.

In theory, warheads slated for destruction are trucked off to the Pantex plant on the sandy Staked Plains outside Amarillo, Texas. There, Department of Energy contractors inspect and gingerly denude them of their non-nuclear components and disassemble their “physics package,” a witch’s brew of high explosives surrounding cores of highly radioactive uranium, plutonium, tritium, and deuterium. Each of these hot, unstable materials is separated and put in storage—some will be carted off for commercial refining, some kept in reserve in case more bombs ever need to be built. The entire process is like performing a ballet blindfolded, in 300-degree heat, on a stage where one slip could kill all the performers.

During the much of the ’90s, the United States took apart its old nukes at a brisk pace—about 1,300 a year. But the process has slowed to a trickle during the past decade. Now a backlog of more than 3,000 warheads sits at the Pantex plant, which may soon run out of storage space altogether. Hans Kristensen, director of the Federation of American Scientists’ Nuclear Information Project, says that this means most newly retired weapons will simply stay on the bases where they were deployed.

During the much of the ’90s, the United States took apart its old nukes at a brisk pace—about 1,300 a year. But the process has slowed to a trickle during the past decade. Now a backlog of more than 3,000 warheads sits at the Pantex plant, which may soon run out of storage space altogether. Hans Kristensen, director of the Federation of American Scientists’ Nuclear Information Project, says that this means most newly retired weapons will simply stay on the bases where they were deployed.

Some of these inactive “zombie” weapons sit in a state of suspended animation, ready to deploy immediately in a submarine, bomber, or silo. Others have specific components removed, though this hardware can be replaced on short notice. According to Peter Fedewa of the pro-disarmament Ploughshares Fund, that amounts to several thousand more nukes “that could be ‘raised from the dead’ and brought back into deployment with relative ease.” (Full disclosure: Ploughshares provides funding to Mother Jones for coverage of national security.)

The New START treaty limits the US and Russia to 1,550 deployed warheads each. It doesn’t, however, limit how many “nondeployed” ICBMs and sub-launched nuclear missiles a nation can keep on ice, just in case. None of these weapons are counted under New START, which means the United States has a shadow force of nuclear weapons waiting in the wings. All told, the United States has several thousand retired, almost-retired, and inactive warheads, according to the Pentagon.

Nuclear hawks in Congress have blunted New START’s planned reductions by stalling dismantlement while beefing up the country’s arsenal of “hedge” weapons—nuclear warheads that aren’t actively deployed for war and thus aren’t touched by the treaty. As Rep. Michael Turner (R-Ohio), chairman of the House Armed Services Strategic Forces Subcommittee, told an audience at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in July, the stockpile of inactive atomic weapons should be seen as a deterrent, implying that if the first 5,000 or so currently deployed warheads can’t deter or defeat America’s enemies, the other few thousand might.

Nuclear secret #2: Disarmament is happening at a snail’s pace.

Making our nukes obsolete is one of the lowest priorities of the nation’s nuclear weapons program. Last summer, Congress and the White House agreed to reduce the amount spent on dismantlement, while agreeing to sink extra cash into plans to increase the usefulness of our semiretired atomic arsenal. In 2012, spending on new nuclear weapons experiments and the construction of “refurbishment” facilities for warheads will increase to $4.1 billion; the government will spend just $57 million on taking apart old nukes, close to half what was spent in 2010—and less than 1 percent of the nuclear complex’s total budget.

The contractors who take old bombs apart are the same ones who pimp out the updated ones. “The public perception is that Pantex is primarily about dismantlement. That’s false,” says Jay Coghlan, the director of Nuclear Watch New Mexico, a source of open-source information on US nuclear weapons facilities. “Dismantlements are basically being done as filler between ‘life extension’ programs.” The dismantlement program, he adds, “is a little bit of a sideshow.”

“The Soviets are long gone, yet the stockpiles remain. The bombs collect dust, yet the bills are with us to this day,” wrote Rep. Ed Markey (D-Mass.) in a recent letter (PDF) to Congress’ budget supercommittee, urging it to slash an “outdated radioactive relic” whose billions could be better spent shoring up Medicare or Social Security. “Fewer nuclear weapons should equal less funding.”

Sixty-five Democratic members of Congress cosigned Markey’s letter. But cutting the nuclear complex down to size remains a tough sell on Capitol Hill. “Nuclear abolition is a long way off,” declared Rep. Turner at a hearing about the nation’s nuclear stockpile in late July. He wasn’t complaining: Turner is one of many Republicans on Capitol Hill who want to keep spending billions on upgrading and “modernizing” our atomic weaponry. “Full funding for nuclear modernization is costly, and difficult in these challenging economic times,” he insisted. “But it is necessary.”

Generally, congressional conservatives’ advocacy for a robust nuclear program has not been tempered by their small-government rhetoric. When New START came before the Senate for ratification in 2010, Sen. Jon Kyl (R-Ariz.)—an atomic-weapons stalwart who’s now a member of the Senate budget supercommittee—blocked a vote until the Obama administration conceded to spending $87 billion “modernizing” the stockpile over the next 10 years.

Nuclear secret #3: Funding for the nuclear weapons complex is growing.

Though the Pentagon controls the bulk of the nuclear weapons budget, the politically powerful National Nuclear Security Administration also has a tight grip on its purse strings. Part of the Department of Energy, the NNSA is responsible for securing the nation’s stockpile as well as overseeing sites where atomic weaponry is built and the nation’s three nuclear labs (Livermore, Los Alamos, and Sandia).

Though the Pentagon controls the bulk of the nuclear weapons budget, the politically powerful National Nuclear Security Administration also has a tight grip on its purse strings. Part of the Department of Energy, the NNSA is responsible for securing the nation’s stockpile as well as overseeing sites where atomic weaponry is built and the nation’s three nuclear labs (Livermore, Los Alamos, and Sandia).

$7.6 billion.

Much of the NNSA’s leadership is drawn from the labs and their allies from top government contracting firms. Its current No. 2 official previously worked in the private sector as a consultant for Sandia Lab and the DOE; its top administrator for defense programs spent three decades running Sandia’s biggest experiments. The NNSA is known for rarely saying no to its labs’ big-ticket demands. “The three labs are accustomed to the style in which they were born,” Coghlan says. “Large and lavish.” Half of NNSA’s budget goes to the labs’ research. Dr. Robert Civiak, a former physicist at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory who now researches the nuclear weapons complex for a network of anti-atomic activist groups, says much of that research is unnecessary. “Its purpose is to improve the fourth-decimal point of our understanding of behavior of nuclear weapons,” he says. “That’s a mature science we’ve had for 70 years.”

In just the past year, the Government Accountability Office has issued four reports criticizing NNSA’s ability to keep control of its operations and costs. “NNSA cannot accurately identify the total costs to operate and maintain weapons facilities and infrastructure,” one states. Another knocks the agency for not properly inspecting its contractors’ work. Yet another found that the agency does not have estimated total costs or completion dates for 15 “vital” projects to keep the stockpile up to date. The reports made 20 recommendations for remedial action.

Yet the White House and Congress continue to increase the labs’ budget. Thanks to the administration’s concessions to congressional Republicans during the New START ratification process, the NNSA will get an additional $85 billion more over the next decade. At a time when federal programs are being scrutinized for fat, the NNSA’s 2012 budget is increasing by 19 percent to $7.6 billion.

Nuclear secret #4: We’re developing the next generation of nuclear weapons.

An hour’s drive from San Francisco, scientists are trying to create a miniature star here on Earth. That’s how the Livermore lab describes its National Ignition Facility, a superlaser that’s supposed to produce nuclear fusion and temperatures of 100 million degrees—conditions found only in distant suns and nuclear explosions. So far, the 14-year old project has been a bust; the New York Times dubbed it a “taxpayer-funded science fiction.” Yet its expense has swelled: It was expected to cost $400 million but has cost $3.9 billion and counting.

Big bucks, little bang: promotional material for the $3.9 billion National Ignition Facility Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Big bucks, little bang: promotional material for the $3.9 billion National Ignition Facility Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

How does the lab justify keeping this far-out science experiment alive in a time of austerity? Simple: national security. Canceling the project, lab director George Miller told the Los Angeles Times when some members of Congress challenged NIF’s funding, is to “seriously question the commitment to maintain nuclear weapons.” Livermore’s research budget has expanded 50 percent since 1994 to nearly $1.5 billion.

The laser project is one of dozens of gold-plated experiments run at the Department of Energy’s three nuclear weapons facilities. The Y-12 National Security Complex in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, is building a new plant to process uranium for the secondary explosives used in warheads, even though the country already has thousands of extra secondaries in storage. In 2004, the plant was expected to cost $600 million; the tab has since increased to $3.5 billion. The federal government is also sinking $4.5 billion into a 1.5 million square-foot plant in Kansas City, Missouri, which will build new components for nuclear weapons.

Y-12, Kansas City, and a nebulous new Los Alamos center for “Chemical and Metallurgy Research Replacement” constitute “grossly oversized facilities for building new bombs we don’t need,” Civiak says. Together, they could facilitate the construction of new warhead cores and missile skins. The labs could test those weapons without live explosions by using technology such as the NIF. “The production side of the US nuclear weapons complex is being rebuilt,” Coghlan says.

Proponents of spending more on the stockpile say that one way to get rid of more warheads is to make sure the ones you hang onto remain in tip-top condition. Rep. Turner has also defended a robust stockpile and modernization as “providing meaningful work to our talented scientists and engineers”—even as he warned that “strategy must drive force structure, not the other way around.”

But critics maintain that modernization is a boondoggle and an expensive make-work program for the nation’s nuclear labs. “There’s no rush to do this,” says Tom Collina, research director of the Arms Control Association, a nonpartisan weapons-policy think tank. Though United States hasn’t built a new warhead since 1989, “it’s not like they’re falling apart; it’s not like they’re Swiss cheese.” The JASON group, a prestigious panel of scientists that advises the government on technology issues, studied the arsenal in 2007 and 2009 and concluded that existing measures could extend the warheads’ lifetimes “for decades, with no anticipated loss of confidence.”

“There’s a lot of things that need regular upkeep on nuclear weapons—batteries and tritium that decay over time,” Civiak explains. But life extension and modernization efforts, he says, are “going way beyond that, and they’re adding new capabilities.”

Upgrades include a “dial-a-yield” option that lets missile officers adjust a warhead’s explosive power; for example, dialing down a 340-kiloton city killer to be a 0.3-kiloton mini-Hiroshima. “Dumb” gravity bombs are being refitted so that the altitude at which they burst can be modified—essentially enabling them to act as “robust nuclear earth penetrators,” or bunker busters.

Civiak says new “safety measures” to adjust the accuracy of atomic missiles will in fact make them potential first-strike weapons. For example, improving missiles’ guidance can turn “countervalue weapons” —big bombs once aimed at population centers as a deterrent—into “counterforce weapons”—tactical nukes that could be used in “limited” nuclear attacks on military or terrorist targets. “Counterforce strays away from deterrence,” Coghlan says.

David Dearborn, a longtime nuclear weapons engineer at the Livermore lab, insists that most of these post-Cold War modifications have safety at their heart. “Earlier, it was about reducing size and weight or getting more bang,” but now “it’s about higher safety, designing things that you could machine-gun and hammer and they would not go off.” As long as the United States has a nuclear stockpile, he says, “You ought to know that it works.”

Advocates of nuclear reduction say that’s a canard. “That sounds nice in theory. Who in principle can be against greater safety?” Coghlan says. But combine all these “safety enhancements,” he says, and “in effect, they’re new warheads.”