Michael Steele.<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/42757699@N04/5094505745">Neon Tommy</a>/Flickr

Is the never-ending and ever-bitter 2012 Republican presidential race—which at this point seems to be alienating independent voters—Michael Steele’s revenge?

In January 2011, Steele, the first African American chair of the Republican National Committee, was unceremoniously denied a second term by the party’s governing council, after a tumultuous two-year stint marked by the historic GOP takeover of the House but also multiple gaffes (Steele called Afghanistan “a war of Obama’s choosing”), blunders (spending $2000 in party funds at a West Hollywood bondage-themed nightclub), and charges of profound financial mismanagement. But during his rocky tenure at RNC HQ, Steele pushed for and won significant changes in the rules for the party’s presidential nomination process and shaped this year’s turbulent race.

These reforms are now bedeviling front-runner Mitt Romney and the Republican establishment by preventing Romney from wrapping up the nomination and keeping him mired in a nasty fight for the support of the party’s hardcore base voters, an ugly and grinding tussle that is defining Romney (and the party) in a manner that’s not bolstering his fall prospects (or the GOP’s). Moreover, the rules Steele bequeathed the party could yield an outcome in which Romney finishes with the most delegates, but not an outright majority, necessitating a brokered convention.

“I wanted a brokered convention,” Steele tells me. “That was one of my goals.” Why in the world would a party chairman desire apparent turmoil? To create excitement and shake up the party, Steele explains. So far this year, he has indeed succeeded in one regard: The Republican race remains unsettled. And that’s unsettling many within the party’s upper ranks.

Not all of the RNC officials at the time craved such creative disorder. Steele, recalls Doug Heye, then the RNC’s communications director, “said in a few interviews that as a political junkie, he’d like to see a brokered convention, and I counseled him that the party chairman may not want to advocate for chaos at a convention he has to manage.” But, in what now seems a profound miscalculation, the Romney camp backed Steele’s reforms—and helped create the monster that now threatens him and the party.

It all started with Obama envy.

Heading into the 2008 convention, Republican leaders, including Steele, a former lieutenant governor of Maryland who was not yet the party’s chairman, saw that the Democratic base was energized, following the exciting, dramatic, and protracted nomination showdown between Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton. That titanic clash had created a sense of momentum for Obama. Steele and other Republicans were jealous.

On the Republican side, John McCain had dispatched Mitt Romney and Mike Huckabee and sewed up the nomination by winning a number of early and big states. Months later, McCain was hardly stirring up the party’s base—or anyone else. (Hence, the soon-to-come Sarah Palin debacle.) Steele and others wanted to rejigger the GOP rules for the 2012 cycle to try to orchestrate a more lively and, perhaps, surprising contest. “We had had a more traditional approach [than the Democrats],” Steele recalls. “If you’re [the candidate] next in line, you get [the nomination]…Yeah, you may be next up, but you may not be the best candidate.”

The GOP can only amend its rules at its nominating conventions—and messing with the rules governing future primary schedules and the allocation of delegates can be a challenging business, especially when there’s a more immediate fight at hand: the upcoming general election. But Steele, who was then chairing GOPAC (a Republican political action committee), and his allies achieved a major victory at the 2008 convention: a change in the rules that afforded them the chance after the convention to devise a one-time rules change for the 2012 campaign schedule. And throughout 2009, after becoming chair of the party, Steele developed a set of proposed reforms for the coming primary contest.

The most obvious matter of contention was which states could have an early primary or caucus. (Florida, Michigan, and others were angling—or threatening—to join the first wave.) Also under consideration for change was the formula for awarding delegates. The Republican contest traditionally had been dominated by winner-take-all states, in which the first-place finisher pocketed all the state’s delegates. Steele favored adding Nevada to the group of early states (Iowa, New Hampshire, and South Carolina), and he fancied proportional allocation of delegates—which would allow candidates who don’t win a state to snatch delegates and remain in the race longer.

The package of proposed rule changes assembled under Steele’s watch aimed to prevent other states from moving their primaries to early February and creating a Super-Duper Tuesday. It “was an effort to combat the tendency in recent election cycles for more and more states to select their delegates earlier and earlier, leading toward the undesirable result of a single, national presidential primary day,” Morton Blackwell, a member of the RNC’s rules committee, noted in 2010. Committee members feared that if 30 or so primaries were held on one day, candidates during this truncated process would focus only on the states with large delegate pools and an advantage would be afforded to those wannabes with large war chests who could buy a ton of ads in these critical states.

The Steele-backed amendment also mandated that states holding their primaries or caucuses in March would have to hand out delegates according to a proportional formula. This presumably would create a disincentive for non-early states to schedule March primaries or caucuses because they would have less clout delegates-wise. But, more important, if delegates were awarded in slices, rather than chunks, the nomination fight could be expected to be more competitive and require more time to generate the party’s standard-bearer. The goal was a primary contest that did not begin too early, that did not end too soon, and that essentially wrapped up by the end of April or early May.

Steele was looking to escape what he calls “the tedium of 2008.” And he had plenty of allies within the party. “I was surprised at how many people liked the idea of creating tension within the process,” he says, “so that an underdog like Rick Santorum could have as much bite or bark as Mitt Romney. Breaking up the line of succession and introducing more fluidity was very appealing to many committee members.”

At a meeting in Kansas City in August 2010, the 168 members of the party’s national committee considered the proposed changes. “Based on what we saw with the Democrats in 2008,” Heye recalls, “we argued that an expanded primary system would benefit the party by leading to a stronger nominee and helping to register more voters.” Some committee members, though, were wary of mirroring the Democrats. “They said, ‘We’re going to fall into their trap,'” Heye notes. The concern: An elongated primary battle would suck up money and time that could be better spent assailing Obama.

Though Steele was hoping to shake things up to make the 2012 race unpredictable, some Republicans suspected the reforms were actually being advanced to assist Romney. They believed that only a well-financed and well-organized candidate would be able to survive and thrive in a prolonged process. “They thought this was fixing the system for Mitt,” a former party official says. And Heye notes, “By and large, if you supported Mitt Romney, you supported the changes.”

Beth Myers, who managed Romney’s 2008 campaign and who advises his current endeavor, for example, backed the notion of starting later and boosting the number of relevant primaries, more or less endorsing the package. Former New Hampshire Governor John Sununu, then chair of his state’s Republican Party and a prominent Romneyite, delivered an impassioned argument at the Kansas City confab in favor of the changes, contending the reforms would impose order on what had seemed to be a chaotic process in 2008.

It was an odd confluence of interests. Steele was yearning to stir the pot. Right-wingers were hoping to avoid a repeat of 2008, when a mainstream Republican outmaneuvered the more conservative candidates. The Romney crew was hankering for a schedule that would best suit a deep-pocketed, well-organized candidate who could go the distance.

After the vote—more than two-thirds of the RNC’s members supported the new rules—Steele declared that the changes “will put our presidential nominating process on the right track and ensure that we emerge from the primaries with the strongest Republican nominee possible to defeat Barack Obama.”

That was the theory. It’s not clear it will turn out that way.

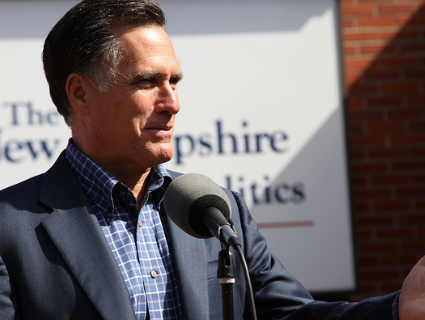

In defiance of the party, Florida moved up its 2012 primary, and Iowa and New Hampshire had to follow to ensure their first-in-the-nation bragging rights. This created a longer front-end than Steele and the others anticipated. And this elongated slog was dominated by vicious Republican-on-Republican brawling, often underwritten by super-PACs. The result has been a primary contest that has turned off Republican voters (turnout is down) and alienated independent voters (Romney’s disapproval rating among indies has soared). “We got the negative aspects without the positive aspects,” Heye laments.

And Romney backers have been complaining about the new system. New Jersey Governor Chris Christie, who has campaigned with Romney, recently called it “the dumbest idea anybody ever had,” and the head of the Vermont GOP likened this year’s reformed schedule to “water torture.” Conservative columnist George Will has practically written off Romney. It seems that this drag-down slugfest will continue for weeks, if not months, for the new rules create an incentive for the non-Romneys to stick it out (and bash away at Romney). With proportional allotment of delegates, Rick Santorum, Newt Gingrich, and Ron Paul can continue to bag delegates that can later be redeemed for influence at the convention—especially if Steele’s dream comes true and Romney ends up short of an all-out majority of delegates and has to reach a backroom arrangement with one of his GOP foes.

Steele, now an MSNBC commentator, has no regrets. “We have captured the national imagination for the last year,” he asserts. “That was not the case four years ago.” But is all publicity truly good publicity? Romney’s image has not improved as he has been stuck in this cat fight with Santorum and Gingrich. (In curious fashion, Paul has refrained from whacking Romney.) Romney may have honed his debating and campaigning skills. But he has not connected with the party’s base. He has not won the admiration of in-the-middle voters. He has not inspired. (His message de la semaine is a technocratic insistence that the delegate math is undeniably in his favor and the rest of the party, including Santorum and Gingrich, ought to just accept that.) At this stage of the race, Romney looks more bruised than bolstered—which was not the case with Obama in 2008.

“A little chaos is a good thing, particularly in a system that tends to be moribund,” Steele says, in defense of his rules. How good—or how bad—cannot be determined until later this year. But Romney and the party could end up paying big time for Steele’s chaos theory experiment.