ZUMA

This is how it was supposed to be for Mitt Romney.

The first presidential debate, on Wednesday night in Denver, demonstrated that it is difficult to defend progress regarding a sluggish economy and far easier to decry the status quo and promise to do better than the guy in charge. Romney repeatedly described President Obama’s actions as failures because the economy remains troubled and claimed he would be the white knight that rides to the rescue. He displayed conviction and passion as he did so, tossing out purported facts and repeatedly referring to Americans he or Ann have met who have shared tales of hardship.

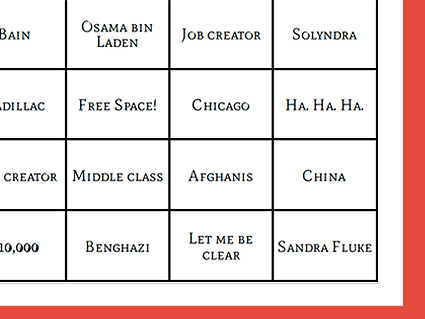

His case against Obama was simply stated: “It’s not working: 23 million out of work, 1 out of 6 in poverty…The path we are taking is not working. It is time for a new path.” Since he entered the race, Romney has wanted this attack to be the organizing principle of the election. But other things got in the way: his lousy campaign skills, his record at Bain Capital, his personal finances (and refusal to release years of his tax returns), his never-ending flubs. Yet once Romney was on the stage with Obama and the topic was the economy, he finally had the chance to spotlight this argument.

Romney looked delighted to be at the debate, assertively accusing Obama of underperformance. Obama came across as more tentative. He certainly had the harder argument to make: saying the economy is moving in the right direction when that movement is not fast enough for millions. But even Obama’s assaults on Romney’s archly conservative policies lacked focus and vigor.

The usual talking points were hurled back and forth. Yet Romney appeared better able to turn his into more specific attacks on Obama, particularly because the president was in a awkward position: How do you defend yourself from the charge that you should have done more? Obama pointed to accomplishments and positive developments in the economy, tax cuts for the middle class, his successful rescue of the auto industry. But that didn’t fully answer Romney’s bottom-line accusation.

The president was also placed at a disadvantage when Romney adopted what might be called the Monty Python defense. Obama repeatedly accused the former Massachusetts governor of proposing a $5 trillion tax cut that would likely increase the deficit, force massive cuts in government spending on education, health care, research, environmental programs, and the like, and lead to higher tax bills for the middle class. In response, Romney essentially said, “It does not.”

Obama referred to studies that supported this conclusion. Romney said that there are other studies that say it does not. When Obama insisted he was accurately describing Romney’s plan, Romney said, no you’re not, and claimed that he would not pass any tax plan that added more to the deficit. Obama said that there was no way Romney could lower tax rates and remain revenue neutral without removing deductions that would hike the tax bill for middle-income families. Nope, Romney said, not so: “I will not add to the deficit with my tax plan.”

Romney was throwing his tax proposal under the bus. But Obama didn’t appear to have a good response to this reality-defying tactic. He wasn’t able to nail Romney squarely for his long-running evasions regarding the deductions he would eliminate to make up for the revenue lost due to lowered tax rates. Romney seemed to be engaged in magical thinking concerning his economic plan—and perhaps discerning viewers picked up on this—but Obama couldn’t quite rattle him.

This was the overall dynamic of the night. Romney stuck to his overall point—Obama has failed to fully resurrect the economy—and he bobbed and weaved in response to Obama’s assault on his assorted positions. When the president asserted that Romney’s budget plan would lead to large cuts in education, Medicaid, and other programs—as the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities has found—Romney merely denied it. On Medicare, Romney stuck with his campaign’s false charge and partially neutralized Obama’s assault on the Romney-Ryan plan that would weaken (and perhaps end) the Medicare guarantee. Romney also fibbed his way through the discussion of Obamacare, especially concerning preexisting conditions. Still, Obama did not score obvious points on that front.

Throughout the campaign, Obama has tried to depict the election as a choice between two visions of how the nation should move forward. At the start of the debate, he pitted his “economic patriotism”—in which the country together invests in education, innovation, and infrastructure to ensure a solid economy in the years ahead—against what he called Romney’s “top-down” economic policies that are premised on the belief that if taxes are cut for the rich and regulations are lifted on corporations, the economy will rev up. But he never seemed to place Romney on the defensive on this mega-theme. On other occasions, Obama has presented this case much more effectively.

Turning Obama’s choice message on its head, Romney basically agreed, Yes, there are two choices: what you got now, or what I’ll give you. And promises are easier to sell than actualities—particularly when they are not bound by facts.

At the start of the campaign, the conventional wisdom was that Obama could have a difficult time winning reelection, given the lousy economy and polls indicating widespread public unease. Yet Romney’s liabilities ensured a competitive race. This first debate showed how challenging the fundamental dynamics are for Obama.

With the president failing to bring his A-game to Denver—and neither he nor moderator Jim Lehrer referred to Romney’s 47 percent rant—Romney took full advantage of the occasion. But given there are so few undecided voters at this point, Romney’s strong performance in a debate that didn’t generate much news or memorable exchanges may not move the needle much. (How many undecideds watched this wonkish debate?) But now that the pundits are once happily declaring, “We have a horse race again,” the Obama crew will have to make sure the president sharpens his case. In a way, he’s always had the tougher sell. This first debate was a painful reminder of that.