Photograph by James West.

IT’S BEEN SEVEN MONTHS since I’ve been inside a prison cell. Now I’m back, sort of. The experience is eerily like my dreams, where I am a prisoner in another man’s cell. Like the cell I go back to in my sleep, this one is built for solitary confinement. I’m taking intermittent, heaving breaths, like I can’t get enough air. This still happens to me from time to time, especially in tight spaces. At a little over 11 by 7 feet, this cell is smaller than any I’ve ever inhabited. You can’t pace in it.

Like in my dreams, I case the space for the means of staying sane. Is there a TV to watch, a book to read, a round object to toss? The pathetic artifacts of this inmate’s life remind me of objects that were once everything to me: a stack of books, a handmade chessboard, a few scattered pieces of artwork taped to the concrete, a family photo, large manila envelopes full of letters. I know that these things are his world.

“So when you’re in Iran and in solitary confinement,” asks my guide, Lieutenant Chris Acosta, “was it different?” His tone makes clear that he believes an Iranian prison to be a bad place.

He’s right about that. After being apprehended on the Iran-Iraq border, Sarah Shourd, Josh Fattal, and I were held in Evin Prison‘s isolation ward for political prisoners. Sarah remained there for 13 months, Josh and I for 26 months. We were held incommunicado. We never knew when, or if, we would get out. We didn’t go to trial for two years. When we did we had no way to speak to a lawyer and no means of contesting the charges against us, which included espionage. The alleged evidence the court held was “confidential.”

What I want to tell Acosta is that no part of my experience—not the uncertainty of when I would be free again, not the tortured screams of other prisoners—was worse than the four months I spent in solitary confinement. What would he say if I told him I needed human contact so badly that I woke every morning hoping to be interrogated? Would he believe that I once yearned to be sat down in a padded, soundproof room, blindfolded, and questioned, just so I could talk to somebody?

I want to answer his question—of course my experience was different from those of the men at California’s Pelican Bay State Prison—but I’m not sure how to do it. How do you compare, when the difference between one person’s stability and another’s insanity is found in tiny details? Do I point out that I had a mattress, and they have thin pieces of foam; that the concrete open-air cell I exercised in was twice the size of the “dog run” at Pelican Bay, which is about 16 by 25 feet; that I got 15 minutes of phone calls in 26 months, and they get none; that I couldn’t write letters, but they can; that we could only talk to nearby prisoners in secret, but they can shout to each other without being punished; that unlike where I was imprisoned, whoever lives here has to shit at the front of his cell, in view of the guards?

“There was a window,” I say. I don’t quite know how to tell him what I mean by that answer. “Just having that light come in, seeing the light move across the cell, seeing what time of day it was—” Without those windows, I wouldn’t have had the sound of ravens, the rare breezes, or the drops of rain that I let wash over my face some nights. My world would have been utterly restricted to my concrete box, to watching the miniature ocean waves I made by sloshing water back and forth in a bottle; to marveling at ants; to calculating the mean, median, and mode of the tick marks on the wall; to talking to myself without realizing it. For hours, days, I fixated on the patch of sunlight cast against my wall through those barred and grated windows. When, after five weeks, my knees buckled and I fell to the ground utterly broken, sobbing and rocking to the beat of my heart, it was the patch of sunlight that brought me back. Its slow creeping against the wall reminded me that the world did in fact turn and that time was something other than the stagnant pool my life was draining into.

Here, there are no windows.

Acosta, Pelican Bay’s public information officer, is giving me a tour of the Security Housing Unit. Inmates deemed a threat to the security of any of California’s 33 prisons are shipped to one of the state’s five SHUs (pronounced “shoes”), which hold nearly 4,000 people in long-term isolation. In the Pelican Bay SHU, 94 percent of prisoners are celled alone; overcrowding has forced the prison to double up the rest. Statewide, about 32 percent of SHU cells—hardly large enough for one person—are crammed with two inmates.

The cell I am standing in is one of eight in a “pod,” a large concrete room with cells along one side and only one exit, which leads to the guards’ control room. A guard watches over us, rifle in hand, through a set of bars in the wall. He can easily shoot into any one of six pods around him. He communicates with prisoners through speakers and opens their steel grated cell doors via remote. That is how they are let out to the dog run, where they exercise for an hour a day, alone. They don’t leave the cell to eat. If they ever leave the pod, they have to strip naked, pass their hands through a food slot to be handcuffed, then wait for the door to open and be bellycuffed.

I’ve been corresponding with at least 20 inmates in SHUs around California as part of an investigation into why and how people end up here. While at Pelican Bay, I’m not allowed to see or speak to any of them. Since 1996, California law has given prison authorities full control of which inmates journalists can interview. The only one I’m permitted to speak to is the same person the New York Times was allowed to interview months before. He is getting out of the SHU because he informed on other prisoners. In fact, this SHU pod—the only one I am allowed to see—is populated entirely by prison informants. I ask repeatedly why I’m not allowed to visit another pod or speak to other SHU inmates. Eventually, Acosta snaps: “You’re just not.”

IF I COULD, I would meet with Dietrich Pennington, a 59-year-old Army veteran from Oakland who has served 20 years of a life sentence for robbery, kidnapping, and attempted murder. Pennington has lived alone in one of these cells for more than four years. During that time, he hasn’t spoken to his family. He has never met any of his seven grandchildren. In the SHU, he’s seen “some of the strongest men I know fall apart.”

But the fact that Pennington is in solitary is not what is remarkable about his story. More than 80,000 people were in solitary confinement in the United States in 2005, the last time the federal government released such data. In California alone, at least 11,730 people are housed in some form of isolation. What is unique about Pennington—if being one of thousands can be considered unique—is that he doesn’t know when, or if, he will get out of the SHU. Like at least 3,808 others in California, he is serving an indeterminate sentence.

Compared to most SHU inmates, Pennington is a newbie. Prisoners spend an average of 7.5 years in the Pelican Bay SHU, the only one for which the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) has statistics. More than half of the 1,126 prisoners here have been in isolation for at least five years. Eighty-nine have been there for at least 20 years. One has been in solitary for 42 years.

Like many of the others, Pennington has never been charged with any serious prison offenses, like fighting or selling drugs. In 20 years of incarceration, his only strikes have been two rule violations: delaying roll call and refusing to be housed in a dorm-style cell with at least seven other prisoners. While in prison, he became a certified welder, receiving a special commendation for his work on building a rollover crash simulator for the California Highway Patrol. He used to regularly attend religious services and self-help groups, including parenting classes, Alcoholics Anonymous, and Narcotics Anonymous, all of which are forbidden in the SHU.

Pennington’s lawyer, Charles Carbone, says his “impeccable prison record” should have him on track for parole. But there is no chance of that—four years ago Pennington was “validated” by prison staff as an associate of a prison gang (one formed on the inside, as opposed to a street gang). That’s the reason he and thousands of others are in the SHU with no exit date.

Pennington is not accused of giving or carrying out orders on behalf of any gang. In fact, there is no evidence that he’s ever communicated with a member of a gang in his entire life. “I’ve never been, never want to be a part of no gang,” he wrote me. (He is currently trying to challenge his validation in court.)

To validate an inmate as a gang member, the state requires at least three pieces of evidence, which must be “indicative of actual membership” or association with a prison gang in the last six years. At least one item must show a “direct link,” like a note or other communication, to a validated gang member or associate. Once the prison’s gang investigator has gathered this evidence, it is reviewed in an administrative hearing and then sent to CDCR headquarters in Sacramento.

In Pennington’s file, the “direct link” is his possession of an article published in the San Francisco Bay View, an African American newspaper with a circulation of around 15,000. The paper is approved for distribution in California prisons, and Pennington’s right to receive it is protected under state law. In the op-ed style article he had in his cell, titled “Guards confiscate ‘revolutionary’ materials at Pelican Bay,” a validated member of the Black Guerilla Family prison gang complains about the seizure of literature and pictures from his cell and accuses the prison of pursuing “racist policy.” In Pennington’s validation documents, the gang investigator contends that, by naming the confiscated materials, the author “communicates to associates of the BGF…as to which material needs to be studied.” No one alleges that Pennington ever attempted to contact the author. It is enough that he possessed the article.

The second piece of evidence was a cup Pennington had in his cell bearing a picture of a dragon, an image CDCR considers an “identifying symbol” of the Black Guerilla Family. The third was a notebook he kept, which the gang investigator alleges “shows his beliefs in the ideals of the BGF.” Its pages are filled with references to black history—Nat Turner, the Scottsboro 9, the number of blacks executed between 1930 and 1969, and quotes from figures like W.E.B. Du Bois and Malcolm X. There are also passages in which Pennington ruminates at length on what he calls “the oppression and violence inflicted upon us here in maximum security,” referencing a Time exposé.

Pennington never mentions gangs or unlawful activity in his writing. But in his validation documents, the gang investigator points out that the notebook contains quotes by Fleeta Drumgo and George Jackson, two former Black Panthers who are revered by members of the BGF and politicized African American prisoners generally. The single Jackson quote Pennington wrote down reads, “The text books on criminology like to advance the idea that the prisoners are mentally defective. There is only the merest suggestion that the system itself is at fault.”

California officials frequently cite possession of black literature, left-wing materials, and writing about prisoner rights as evidence of gang affiliation. In the dozens of cases I reviewed, gang investigators have used the term “[BGF] training material” to refer to publications by California Prison Focus, a group that advocates the abolition of the SHUs; Jackson’s once best-selling Soledad Brother; a pamphlet said to reference “Revolutionary Black Nationalism, The Black Internationalist Party, Marx, and Lenin”; and a pamphlet titled “The Black People’s Prison Survival Guide.” This last one advises inmates to read books, keep a dictionary handy, practice yoga, avoid watching too much television, and stay away from “leaders of gangs.”

The list goes on. Other materials considered evidence of gang involvement have included writings by Mumia Abu-Jamal; The Black Panther Party: Reconsidered, a collection of academic essays by University of Cincinnati professor Charles Jones; pictures of Assata Shakur, Malcolm X, George Jackson, and Nat Turner; and virtually anything using the term “New Afrikan.” At least one validation besides Pennington’s referenced handwritten pages of “Afro centric ideology.”

As warden of San Quentin Prison in the 1980s, Daniel Vasquez oversaw what was then the country’s largest SHU. He’s now a corrections consultant and has testified on behalf of inmates seeking to reverse their validations. As we sat in his suburban Bay Area home, he told me it is “very common” for African American prisoners who display leadership qualities or radical political views to end up in the SHU. Similarly, he recalls, “we were told that when an African American inmate identified as being Muslim, we were supposed to watch them carefully and get their names.”

Vasquez testified in federal court in the case of a former inmate, Ernesto Lira, who was gang validated in part based on a drawing that included an image of the huelga bird, the symbol of the United Farm Workers. While the image has been co-opted by the Nuestra Familia prison gang, Vasquez testified that it is “a popular symbol widely used in Hispanic culture and by California farmworkers.” Lira’s validation was one of a handful to ever be reversed in federal court—though not until after he was released on parole, having spent eight years in the SHU. And though the court ruled that the huelga bird is of “obscure and ambiguous meaning,” it continues to be used as validation evidence.

Gang evidence comes in countless forms. Possession of Machiavelli’s The Prince, Robert Greene’s The 48 Laws of Power, or Sun Tzu’s The Art of War has been invoked as evidence. One inmate’s validation includes a Christmas card with stars drawn on it—alleged gang symbols—among Hershey’s Kisses and a candy cane. Another included a poetry booklet the inmate had coauthored with a validated BGF member. One poem reflected on what it was like to feel human touch after 14 years and another warned against spreading HIV. The only reference to violence was the line, “this senseless dying gotta end.”

“Direct links” that appear in inmates’ case files are often things they have no control over, like having their names found in the cells of validated gang members or associates or having a validated gang affiliate send them a letter, even if they never received it or knew of its existence. Appearing in a group picture with one validated gang associate counts as a direct link, even if that person wasn’t validated at the time.

In the course of my investigation, I obtained CDCR’s confidential validation manual. It teaches investigators that use of the words tío or hermano, Spanish for uncle and brother, can indicate gang activity, as can señor. Validation files on Latino inmates have included drawings of the ancient Aztec jaguar knight and Aztec war shields, and anything in the indigenous Nahuatl language, spoken by an estimated 1.4 million people in central Mexico.

Lieutenant David Barneburg has the power to decide who’s put into solitary for years—or decades. Photo by Shane Bauer.Some SHU inmates, aside from the “bona fide gang members,” are those “the guards don’t like,” says Carbone, Pennington’s lawyer. “They get annihilated with gang validations in order to get them off the main lines…The rules are so flimsy that if the department wants somebody validated, he will get validated.”

Lieutenant David Barneburg has the power to decide who’s put into solitary for years—or decades. Photo by Shane Bauer.Some SHU inmates, aside from the “bona fide gang members,” are those “the guards don’t like,” says Carbone, Pennington’s lawyer. “They get annihilated with gang validations in order to get them off the main lines…The rules are so flimsy that if the department wants somebody validated, he will get validated.”

California is just one of many states where inmates can be thrown into solitary confinement on sketchy grounds—though just how many is hard to know. A survey conducted by Mother Jones found that most states had some kind of gang validation process, but implementation varied widely, and a number of states would not disclose their policies at all. Seventeen states said they don’t house inmates in “single-celled segregation” indeterminately. (No state officially uses the term “solitary.”)

It’s unclear how many states keep inmates in solitary as long as California does. Texas has 4,748 validated affiliates of “security threat groups” in indefinite solitary—more than California’s prison gang affiliates—and some have been there for more than 20 years. Louisiana has held two Black Panthers in solitary for 40 years. Minnesota is near the opposite end of the spectrum, holding inmates in segregation for an average term of 29 days. At least 12 states review an inmate’s segregation status every 30 days or less; Massachusetts does it weekly.

Keeping all these inmates segregated is an expensive proposition for taxpayers. Pelican Bay spends at least 20 percent more to keep an inmate in isolation—an extra $12,317 per inmate per year, or $14 million annually.

AT PELICAN BAY, decisions about who gets put in the hole indefinitely come down to one man: Institutional Gang Investigator David Barneburg. A stocky man with a shaved head and a seven-point star on the breast of his khaki uniform, Barneburg comes from a lineage of loggers who found themselves out of work when the timber industry busted. When Pelican Bay opened its doors amidst the majestic redwoods in 1989, his father signed up.

Pelican Bay was a new kind of prison—one of the nation’s first full-fledged supermaxes, built with the explicit purpose of housing inmates in long-term isolation. After Pelican Bay, supermaxes popped up across the country, in part to deal with rising violence in increasingly crowded prisons. Today, there are roughly 60 nationwide.

Barneburg started here in 1997, and after 15 years on the job, he comes off as a man under duress. He makes a point of assuring me that he and his gang investigations team of 10 are not “knuckle-dragging thugs.” He tells me he has to regularly take the stand in court to defend gang validations. To date, prisoners have sued him at least 30 times, though I could find no record of any having succeeded. “I don’t want to go as far as saying gang investigators are persecuted, but…”

He is giving me a PowerPoint presentation detailing the structures and operations of the seven prison gangs targeted by the department of corrections. The Nazi Low Riders. The Aryan Brotherhood. The Texas Syndicate. The Black Guerilla Family. The Mexican Mafia. The Nuestra Familia. The Northern Structure. “It’s about power,” he says. “It’s about control. It’s about extortion. It’s about money. It’s about dope. It’s about murder.” Membership in a gang is not illegal in the United States—it’s a right protected by the First Amendment—but Barneburg says segregating gang members is the only way to keep prisons from being overrun by racial strife, stabbings, and killings.

When I ask him how well that’s worked, he stutters and says diffidently, “I think there’s been less violence.”

He’s wrong. The rate of violent incidents in California prisons is nearly 20 percent higher than when Pelican Bay opened in 1989. As I walk with Lieutenant Acosta alongside the general population yard—a grassy, if bleak, fenced-in area where, unlike in the SHU, prisoners are allowed to interact—he unwittingly contradicts Barneburg’s claim too, saying that violence in Pelican Bay has seen dramatic spikes over the years. In the 1990s, he says, “you didn’t see the big fights, all the riots. It was like one, two guys fighting, maybe three guys.” But since then, prison gang violence has escalated dramatically, with riots involving upwards of 200 people.

Prison violence fluctuates for myriad reasons, among them overcrowding, gang politics, and prison conditions. It’s impossible to say for certain what role SHUs play; what is clear is that in states that have reduced solitary confinement—Colorado, Maine, and Mississippi—violence has not increased. (Illinois plans to close its notorious Tamms supermax soon.) Since Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman released 75 percent of inmates from solitary in the mid-2000s, violence has dropped 50 percent.

CDCR officials claim California is different because the gang problem is worse here, though they don’t have data to confirm this. Barneburg says without SHUs, there would be no way to prevent gang leaders from giving orders to the general population. What he doesn’t say is that very few SHU inmates are considered gang leaders even by CDCR’s standards. Only 22 percent of those serving indeterminate SHU terms are validated even as members of prison gangs. The rest, like Dietrich Pennington, are classified as associates, people who are accused of having had some connection with members—or other associates—of prison gangs.

Former San Quentin Warden Daniel Vasquez says association with prison gangs—for protection, among other things—is “pretty inescapable” in the hostile and racially segregated atmosphere inside. “You’re going to come across them in some form or fashion,” he says. “You are going to start experiencing the pressures of these gangs.” Barneburg himself acknowledges it is hard for a Mexican from Southern California, for example, to keep away from the Mexican Mafia, since the gang sees itself as the authority over any Mexican prisoner from the lower part of the state. A full 2,201 people currently serving indeterminate SHU terms are validated as associates of that gang; there are only 98 validated members.

Being associated with a prison gang—even if you haven’t done anything illegal—carries a much heavier penalty than, say, stabbing someone. Association could land you in solitary for decades. An inmate who murders a guard—the severest crime in prison—can get no more than five years in the SHU.

THE DECISION to put a man in solitary indefinitely is made at internal hearings that last, prisoners say, about 20 minutes. They are closed-door affairs. CDCR told me I couldn’t witness one. No one can.

When Josh Fattal and I finally came before the Revolutionary Court in Iran, we had a lawyer present, but weren’t allowed to speak to him. In California, an inmate facing the worst punishment our penal system has to offer short of death can’t even have a lawyer in the room. He can’t gather or present evidence in his defense. He can’t call witnesses. Much of the evidence—anything provided by informants—is confidential and thus impossible to refute. That’s what Judge Salavati told us after our prosecutor spun his yarn about our role in a vast American-Israeli conspiracy: There were heaps of evidence, but neither we nor our lawyer were allowed to see it.

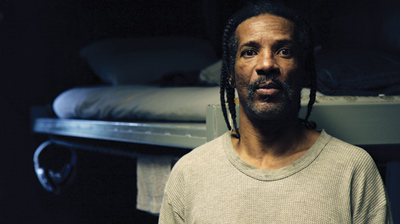

Ronald Brown, a prisoner who was moved from SHU into another prison unit Photo by James West.None of the gang validation proceedings, from the initial investigation to the final sentencing, have any judicial oversight. They are all internal. Other than the inmate, there is only one person present—the gang investigator—and he serves as judge, jury, and prosecutor. After the hearing, the investigator will send his validation package to Sacramento for approval. The chances of it being refused are vanishingly small: The department’s own data shows that of the 6,300 validations submitted since 2009, only 25 have been rejected—0.4 percent. “It’s pretty much a rubber stamping,” Vasquez says.

Ronald Brown, a prisoner who was moved from SHU into another prison unit Photo by James West.None of the gang validation proceedings, from the initial investigation to the final sentencing, have any judicial oversight. They are all internal. Other than the inmate, there is only one person present—the gang investigator—and he serves as judge, jury, and prosecutor. After the hearing, the investigator will send his validation package to Sacramento for approval. The chances of it being refused are vanishingly small: The department’s own data shows that of the 6,300 validations submitted since 2009, only 25 have been rejected—0.4 percent. “It’s pretty much a rubber stamping,” Vasquez says.

“That is a system that has no place in a constitutional democracy,” says David Fathi, director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s National Prison Project. He says California’s policy is “a form of guilt by association that is completely foreign to our legal system. Prison administrators have absolute power, and that is a recipe for abuse and violation of rights.”

CDCR officials are quick to point out that inmates can challenge their gang status: They can appeal to the gang investigator, the warden, and, as a last resort, the departmental appeals office in Sacramento. But former Pelican Bay Warden Joseph McGrath testified in court that “officers do not reevaluate the evidence” and that, if an appeal came to him, he would “assume the truth of whatever was written” in the validation documents. When I asked CDCR for an example of an appeal resulting in a reversal of a gang validation, they couldn’t produce a single case. Gang investigator Barneburg, who has worked at Pelican Bay for 15 years, has never seen a validation appeal succeed either—evidence, he says, of his team’s thoroughness. “We put out really quality work,” he says.

If an inmate exhausts his administrative appeals, he has the legal right to take his case to court. Most can’t afford a lawyer, so they end up representing themselves. Attorney Charles Carbone, who has challenged more than 200 gang validations (of which he says about 25 have been successful), says inmates who represent themselves succeed “less than 1 percent” of the time. The biggest obstacle is the “some evidence” standard, which essentially means that CDCR only has to provide a bare minimum of proof. The courts do not weigh the evidence or decide whether or not a prisoner is in a gang. The judge’s job is only to “see whether any evidence exists,” Carbone says. “And if it does, he won’t evaluate it. He’ll leave that to the prison authorities.”

HOW DOES someone get out of the SHU, then? Officially, there are two ways. One is to be declared an “inactive” gang member or associate, which doesn’t happen very often. Just a few dozen inmates are released to the general population every year via that process—less than 1 percent of those serving indeterminate SHU terms. The earliest chance of being classified as “inactive” is six years from the latest evidenced gang activity. Then, if a gang investigator provides a single piece of new evidence—say a book found in the cell or a tidbit from a confidential informant—the inmate has to wait six more years.

When Paul Bocanegra got out of solitary, he says it felt “like you’re free.” Photo by James West.The other way out is to debrief—to divulge everything an inmate knows about a gang, including names of members and associates. This he can do at any time. An average of 108 do it every year, even though among prisoners snitching can carry the death penalty.

When Paul Bocanegra got out of solitary, he says it felt “like you’re free.” Photo by James West.The other way out is to debrief—to divulge everything an inmate knows about a gang, including names of members and associates. This he can do at any time. An average of 108 do it every year, even though among prisoners snitching can carry the death penalty.

And what if a prisoner in the SHU doesn’t know anything? As former Pelican Bay Warden McGrath testified in court three years ago, anyone mistakenly validated “cannot debrief,” because they have nothing to give. Catch-22.

In Pelican Bay’s Transitional Programming Unit—the place where inmates go once they’ve been released from the SHU—I sit at a metal table with Paul Bocanegra, a burly, tattooed former prison gang member. He spent 12 years in isolation before he debriefed. Now, he is housed among other debriefers and will probably never go back to the general population. Assault or murder, he says, is “usually what happens once you turn your back on your buddies—people you used to run with. That’s always in the back of your head. What’s gonna happen if one day I get out, you know?”

CDCR claims that indeterminate SHU sentences are not meant to be punitive but are simply intended to isolate dangerous prisoners. That’s also the argument the department uses to refute challenges like the class action lawsuit under way by the Center for Constitutional Rights on behalf of Pelican Bay prisoners who have spent between 10 and 28 years in solitary. The suit claims that prolonged SHU confinement is cruel and unusual punishment.

Is it not? In the SHU, no work, drug treatment programs, or religious services are permitted. SHU prisoners are not allowed phone calls (except in approved emergencies) or contact visits. Clocks, photo albums, food condiments containing sugar (like ketchup), playing cards, and chessboards are all banned. Only after a nearly three-week-long hunger strike last year were SHU inmates allowed calendars, as well as handballs to use in the concrete dog run. Their monthly canteen draw is a quarter of the regular population’s allowance, as is the one 30-pound package they can receive per year. Pelican Bay Warden Greg Lewis insists this, too, isn’t to punish them, but to provide “a very safe environment.”

When I ask Bocanegra if the SHU is punishment, he laughs. “It’s meant to break a person,” he says. “You have to accept whether you want to die back there or you want to change.” Leaving the SHU for a unit where he can exit his cell without cuffs and go to an outdoor exercise yard with a small group of other people, he says, made him “feel like you’re free.” When he walked out of the SHU, he saw his first tree in 12 years.

EVERY DAY, I come home to a new stack of letters from prisoners—our hostage story, it seems, is best known inside America’s penitentiaries. For a while, I try to respond to each one, but as the weeks and months pass, they start to pile up. I become afraid of them and all the sorrow they contain. They take me back to my own time in solitary—and how can I go back there every day?

One morning, I sit down at my desk and look at the stack of envelopes slowly taking it over. I need to write these people back. I know what it’s like to wait for word from the outside. Some of them remind me of myself while I was locked up, their whole lives bent on staying sane. They write. They read. They exercise. They meditate. Others make me think of what I would have eventually become. Their letters don’t make sense. They write me constantly, desperately. They are broken.

Instead of digging into the pile, I place a stack of 18 postcards in front of me and write on each of them a question that has been on my mind since I left Pelican Bay: “Do you think prolonged SHU confinement is torture?” I send them to prisoners across the state and 14 write back, all with the same answer: “yes.” One tells me he has developed a condition in which he bites down on his back teeth so hard he has loosened them. They write: “I am filled with the sensation of drowning each and every day.” “I was housed next door to…guys who have eaten and drank their own body waste and who have thrown their own body waste in the cells that I and others were housed in. I cry.”

There are plenty of studies about the psychosis-like symptoms that result from prolonged solitary. Indicators of what psychiatrist Stuart Grassian calls “SHU syndrome” include confusion and hallucination, overwhelming anxiety, the emergence of primitive aggressive fantasies, persecutory ideation, and sudden violent outbursts.

As I read the medical literature, I remember the violent fantasies that sometimes seized my mind so fully that not even meditation—with which I luckily had a modicum of experience before I was jailed—would chase them away. Was the uncontrollable banging on my cell door, the pounding of my fists into my mattress, just a common symptom of isolation? I wonder what happens when someone with a history of violence is seized by such uncontrollable rage. A 2003 study of inmates at the Pelican Bay SHU by University of California-Santa Cruz psychology professor Craig Haney found that 88 percent of the SHU population experiences irrational anger, nearly 30 times more than the US population at large.

Haney says there hasn’t been a single study of involuntary solitary confinement that didn’t show negative psychiatric symptoms after 10 days. He found that a full 41 percent of SHU inmates reported hallucinations. Twenty-seven percent have suicidal thoughts. CDCR’s own data shows that, from 2007 to 2010, inmates in isolation killed themselves at eight times the rate of the general prison population.

In the SHU, people diagnosed with mental illnesses like depression—which afflicts, according to Haney, 77 percent of SHU inmates—only see a psychologist once every 30 days. Anyone whose mental illness qualifies as “serious” (the criterion for which is “possible breaks with reality,” according to Pelican Bay’s chief of mental health, Dr. Tim McCarthy) must be removed from the SHU. When they are, they get sent to a special psychiatric unit—where they are locked up in solitary. Some 364 prisoners are there today.

Is long-term SHU confinement torture? The ACLU says yes. Physicians for Human Rights agree. The Center for Human Rights and Constitutional Law and several other prisoner rights groups recently filed a petition with the United Nations claiming just that. Human Rights Watch says at the very least, it constitutes cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment, which is prohibited by international law.

Prisoners in Pelican Bay’s Housing Unit are allowed into the “dog run,” a.k.a. exercise yard, alone, for an hour each day. Photo by Shane Bauer.UN Special Rapporteur on Torture Manfred Nowak once sent a letter to Tehran to appeal on behalf of my fellow hostage, and now wife, Sarah Shourd. Though Josh and I were celled together after four months, Sarah remained in isolation, seeing us for only an hour a day. Late last year, Nowak’s successor, Juan Mendez, came out with a report in which he called for an international prohibition on solitary confinement of more than 15 days. He defined solitary as any regime where a person is held in isolation for at least 22 hours a day. Anything more “constitutes torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, depending on the circumstances.” When I called Mendez to ask about the SHU, he said, “I don’t think any argument, including gang membership, can justify a very long-term measure that is inflicting pain and suffering that is prohibited by the Convention Against Torture.”

Prisoners in Pelican Bay’s Housing Unit are allowed into the “dog run,” a.k.a. exercise yard, alone, for an hour each day. Photo by Shane Bauer.UN Special Rapporteur on Torture Manfred Nowak once sent a letter to Tehran to appeal on behalf of my fellow hostage, and now wife, Sarah Shourd. Though Josh and I were celled together after four months, Sarah remained in isolation, seeing us for only an hour a day. Late last year, Nowak’s successor, Juan Mendez, came out with a report in which he called for an international prohibition on solitary confinement of more than 15 days. He defined solitary as any regime where a person is held in isolation for at least 22 hours a day. Anything more “constitutes torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, depending on the circumstances.” When I called Mendez to ask about the SHU, he said, “I don’t think any argument, including gang membership, can justify a very long-term measure that is inflicting pain and suffering that is prohibited by the Convention Against Torture.”

CDCR, like correctional departments around the country, does not consider the SHU solitary confinement. Inmates have TV, and they have contact with staff when they bring them their food, officials told me. Our interrogators in Iran said the same thing.

JOSH AND I used to make up stories about other prisoners who walked past our cell, blindfolded, on their way to the bathroom. In our imaginations, the man who looked to be in his mid-30s with a smooth head and a slim build was the lead singer in an alternative rock band. His anguish was fueled by the fact that the government deemed his music subversive, when all he wanted was to play his guitar. The grizzled old man was a playwright. The guy with the long beard was an imam. The clean-cut twentysomething was an internet hacker.

Lately, it’s like I’ve been doing the opposite—shaping living, breathing people out of snatches of information. Vincent Bruce has written me more than 20 times, and I’ve read through hundreds of pages of his court and prison files. From this, I can tell you that the 50-year-old has spent nine and a half years in isolation—seven of them alone in the SHU—but I can’t tell you whether it shows in his stride like I could with the guys who walked past my cell. I can tell you that when he was 26, he busted out of jail in Chicago, that The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire is one of his favorite books, and that he loves Phil Collins’ “In the Air Tonight.”

I can tell you that he is one of California’s most effective jailhouse lawyers. This is how his days pass: At six o’clock every morning, he wakes up, washes his face, and scrubs the floor of his cell. He does half an hour of yoga and meditation. From noon until dinnertime, he sits hunched over on his bed and pores over whatever legal case he is working on. Sometimes he gets diverted and watches court shows. It’s one of his weaknesses.

When Bruce was a kid, he says, his mom had nervous breakdowns when she would turn into a zombie that he had to feed and bathe. Her boyfriend’s solution was to “slap her out of it.” At 13 or 14 he started running with the Crips. Since then, he has spent a total of about one year on the outside. At 23, he was convicted of three counts of first-degree murder, two counts of attempted murder, and two counts of first-degree robbery, and sentenced to life without parole.

Several years into his incarceration, he started to organize other prisoners. In the 1990s at Salinas Valley State Prison, he crossed the intense racial divide of prison and organized 74 black, white, and Latino prisoners to pressure the administration into providing family visitation, religious services, and better food.

In 1998, Bruce was put in administrative segregation for allegedly assaulting another inmate. Ad-seg, as it is commonly known, is a solitary unit in each prison where inmates are often placed for disciplinary infractions. Some 6,700 California prisoners are in such units.

Bruce’s ad-seg term was supposed to last 90 days. While there, he started pushing for improvements—allowing ad-seg inmates access to the exercise yard, reading and writing materials, the law library, and adequate bedding and clothing. Shortly afterward, he was told he wouldn’t be getting out of isolation: He was under investigation for gang affiliation. (His time in the Crips, which he says ended years ago, was irrelevant here—indeterminate SHU terms are only given for connections with prison gangs.)

This had happened before, but investigators had determined the evidence “insufficient.” This time—using the same evidence—Bruce was validated and transferred to the Pelican Bay SHU. He denies ever affiliating with a prison gang.

Bruce would later write in a legal complaint that the gang investigator told him the goal was to “make an example out of him” because he was acting as a “spokesperson for other prisoners’ grievances.” It would be nearly three years before he had direct contact with another human being.

In 1999, Bruce sued the department of corrections, claiming he had been put in the hole for being a jailhouse lawyer. Thanks to his legal pestering, the court eventually appointed him an attorney. The case dragged on for seven years. Meanwhile, he was released from the SHU as an “inactive” gang associate and transferred to another prison, where he continued his advocacy, winning at least 25 concessions over a period of six years, including wheelchair-accessible tables for the yard. At one point he initiated a hunger strike that involved 120 inmates. Two days later, he was put in ad-seg for “conspiracy to assault staff.” The claim was based on confidential information that the person in charge of reviewing ad-seg assignments later found did not exist; it couldn’t be found anywhere in his file. He spent a year in isolation.

About a year after Bruce was released from ad-seg, CDCR agreed to a settlement in his retaliation suit, paying him $7,500 and guaranteeing him adequate due process in the future. Ten days later, two assistant gang investigators came to Bruce’s cell and confiscated his legal materials, a violation of California law. That same day, he was placed in ad-seg for possession of a shiv. Prison officials later acknowledged that the weapon didn’t belong to him, but the charge was never dropped, and he was sent to the SHU to serve a 10-month sentence.

The gang investigator meant to keep him there. In yet another gang validation package, he claimed Bruce’s retaliation case against CDCR in itself constituted “gang activity.” In January 2008, he was validated as an associate of the BGF and his SHU sentence was extended indefinitely. The evidence against him was confidential. He has been in the SHU ever since.

Six months after his indefinite SHU term began, he received a letter from a young man he’d been celled with a few years before. “Although I tried my best not to let you know I was listening to you,” the other prisoner wrote, “my ears was always open when you spoke. Vincent you have made me a wise young man, and did something for me I will never forget.” Now, he wrote, “The gang banging life is over with.”

INFORMATION obtained from prisoners in solitary has long been viewed with suspicion. Numerous psychological studies have found that the more people are subject to sensory deprivation, the more suggestible they become. A 1961 US Air Force study titled “The Manipulation of Human Behavior” cast this as a plus, saying, “Solitary confinement and monotonous, barren surroundings play an important role in making the prisoner more receptive and susceptible to the influence of the interrogator.” After the public disclosure of the CIA’s 1983 “Human Resource Exploitation Training Manual,” which taught agents how to extract confessions without leaving bruises, the agency renounced the use of “coercive interrogation techniques,” including solitary confinement, in part because they yielded “unreliable results.”

In California, much of the information used to validate prisoners comes from the 108 inmates who debrief every year, creating a revolving door where people get out of the SHU by putting others in. Pelican Bay gang investigator David Barneburg insists that all information is double-checked against information provided by other sources. But as long as this information is kept secret from everyone, including lawyers, that vetting is left up to investigators—and there’s evidence that they are not immune to the temptation to make things up.

In 2006, a prisoner with a violence-free prison record named Ricky Gray was validated as a member of the Black Guerilla Family and given an indeterminate SHU sentence. But the warden at his prison, who Gray claims was sympathetic to his case, took an unusual step: He instructed a staff assistant to reinterview the informants who had given evidence against him. The assistant concluded that the entire validation package was “comprised of conjecture, second hand expression, assumptions, frivolous statements, incomplete documentation, and blatant lack of thorough investigation.” Gray managed to obtain a copy of this confidential report, and his lawyer passed it to me, providing a rare glimpse of the type of evidence used in gang validations.

Several of the alleged informants, the assistant wrote, didn’t know Gray at all. Two others—said to have reported that Gray was recruiting inmates to the BGF—signed sworn affidavits that they had never been interviewed about the subject and didn’t know the guard who compiled their alleged statements. The paperwork that allegedly documented their statements didn’t bear their signatures. In another of the interviews used against Gray, the staff assistant says the gang investigator appeared “to be leading” the informant “to answer questions the way he would like.”

Like Bruce, Gray believes the gang investigator retaliated against him for his work as a jailhouse lawyer, a role in which he has been particularly successful—his biggest victory was an Eighth Amendment claim against prison guards that won him a $115,000 settlement from CDCR. Indeed, his legal work is specifically referenced in his validation. One piece of evidence pointedly stated that Gray’s “use of correspondence for legal purposes is well documented.”

The staff assistant’s review recommended that Gray be classified as an “inactive” gang member and stated that Gray “does not have a problem following the rules once he is aware of them.” But six years later, Gray remains in the SHU. The warden who ordered the review transferred to another prison 37 days after it was completed, and the gang investigator—the same man who presided over Gray’s validation in the first place—chose not to change Gray’s validation status in response to the investigation. When Gray took the matter to court, the judge ruled that “a prisoner has no constitutionally guaranteed immunity from being falsely or wrongfully accused of conduct which may result in the deprivation of a protected liberty interest.” In other words, it is not illegal for prison authorities to lie in order to lock somebody away in solitary.

AT SOME POINT during the disorienting reentry blitz that followed my release in September of last year, I heard that in California, prisoners were doing what the three of us had done in Iran: hunger striking to protest isolation. Up to 12,000 inmates participated in protests against long-term SHU confinement across the state, making it probably the largest prison strike in recent history—twice the size of the one that took place a few months earlier. The prisoners were demanding changes to the gang validation policy and an end to long-term solitary.

Implicit in the two hunger strikes was a message: The use of prolonged solitary confinement was leading to the kind of unrest it was meant to tamp down. Nearly three weeks into the 2011 strike, CDCR promised to make changes to its gang validation policy. Since then, it has been hammering out a set of reforms, aimed primarily at turning the policy into a “behavior-based” one. This would bring California in line with other states that—at least on paper—segregate people only when they engage in violent or dangerous activity.

The new policy, which is already being rolled out on a pilot basis, will also include a “step down” program that would allow inmates to work their way out of the SHU over a four-year period, rather than wait six years before their case is even reviewed. After a year of abstaining from gang activity in the SHU, an inmate will be able to get one phone call per year, a deck of cards, and the ability to spend 11 more dollars at the canteen every month. After three years, he’ll be allowed a chessboard, and his family will be able to send him two packages each year rather than one.

Department officials in Sacramento wouldn’t talk to me about the new policy—after my visit to Pelican Bay, they declined further interviews, citing pending litigation. But when I talked to CDCR spokeswoman Terry Thornton about the reforms, she said, “I think you are going to see a lot of people classified as associates getting out of the SHU.” Under the new policy, associates—unlike members—of prison gangs will only be put in the SHU if they commit a “serious” rule violation or two “administrative” rule violations.

Here’s the catch, though: CDCR is vastly expanding what counts as rule violations. Under current regulations, “serious” violations are things like assaults, drug use, and escape attempts. But in the latest version of the reforms, the definition includes possession of “training material” for security threat groups (the new term for gangs), like the books listed earlier. Things that didn’t previously count as a rule violation—such as making artwork depicting threat-group symbols, communication showing threat-group behavior, and anything that “depicts affiliation” with a threat group—will all be serious rule violations on par with stabbing somebody. “Administrative rule violations” will now include many new categories, such as possession of photos of validated threat-group affiliates.

Most critically, the new security threat group category doesn’t just denote prison gangs, but also includes a much larger number of “disruptive groups.” Among these are street gangs, motorcycle gangs, and “revolutionary groups.” The list of disruptive organizations that CDCR gave me runs to 1,500, including not only the Bloods and Crips, but also the Juggalos, the dedicated clown-faced following of the dual-platinum horrorcore hip-hop group Insane Clown Posse. The Black Panthers are on the list, as are a couple of Nation of Islam-affiliated groups. One category is titled “Black-Non Specific,” suggesting that any group with the word “black” in its name can be considered disruptive. (CDCR would not respond to my questions on this matter.)

Taken together, the policy changes could mean that a Crip taking part in a hunger strike, a Black Panther with a drawing he made of his organization’s namesake cat, or an Insane Clown Posse fan with an album cover and a concert photo could receive indeterminate SHU terms.

ONE NIGHT, I stare at the pile of letters on my desk. I can’t let it keep growing, so I take it over to the couch and read through them all. It’s painful. A part of me relates to these people, but, like I wanted to tell Lieutenant Acosta when I stood in that cell, there are such huge differences too. They are criminals; I was a hostage. They are spending many years in solitary; I did four months.

But still, I can’t escape the fact that their desperate words sound like the ones that ricocheted through my own head when I was inside. When I finish the stack of letters, I dig up the first correspondence I ever received from a prisoner. He has been out of the SHU for years, but through his florid prose, I hear the voice of someone who is still profoundly disturbed by the time he did there.

March 27, 2012

…Like you, I know what it is like to have our very existence internalized to the point of kissing Siren on the lips while she guided us to the rocks of insanity. Then, wondering if we’d ever escape her spell. Fortunately we both did. But as you will learn about you and me, we did not come out unscathed. At times…I mourn the solitude of days gone past. Days where time lost all meaning; to the point where I knew not if I was alive or dead; and where sometimes I did not care either way…

—Steve Castillo

After I read this, I go to the big wicker chest at the foot of our bed. In it are letters written to me by friends, family, and strangers that I never received because the Iranian censors would only let in mail from immediate family. There are hundreds of these; I keep them because I think I might read them some day. But not now. Instead, I grab a little piece of paper that is covered in microscopic writing, the script so small and the shorthand so esoteric that I can hardly read it, even though it was written by my own hand. It is the only piece of my prison journal—written on scraps of paper and hidden in the spines of books—that made it out.

The more one is utterly alone, the more the mind comes to reflect the cell; it becomes blank static…

Solitary confinement is not some sort of cathartic horror of blazing nerves and searing skin and heads smashing blindly into walls and screaming. Those moments come, but they are not the essence of solitary. They are events that penetrate the essence. They are stones tossed into an abyss. They are not the abyss itself…

Solitary confinement is a living death. Death because it is the removal of nearly everything that characterizes humanness, living because within it you are still you. The lights don’t turn out as in real death. Time isn’t erased as in sleep…

I carefully fold up the note, put it back in the chest, and step out onto our little second-story porch, into the breeze and the sun.