A printed plastic receiver for an AR-15 fell apart after just six shots.Defense Distributed

Rep. Steve Israel wants to stop you from making assault rifles with a 3-D printer.

On December 7th, the New York Democrat announced plans to introduce a bill to reauthorize the Undetectable Firearms Act, which prohibits the sale, transport, and manufacture of weapons that can’t be spotted by a metal detector. Set to expire next year, the law was originally passed in 1988 to stop the anticipated-but-never-realized spread of plastic weapons. This time, Israel has set his sights on something decidedly more sci-fi: “Remember ‘Replicators’ on #Star Trek?,” he tweeted earlier this month. “Now gun parts can be replicated with 3-D printers. Introducing [a] bill to stop so-called ‘wiki-weapons.'”

3-D printers, which “print” objects out of plastic by using digital blueprints, have exploded among DIYers over the last few years, fueled by the rise of companies like MakerBot. Thingiverse, an online library of blueprints hosted by MakerBot, holds tens of thousands of blueprints—for everything from engagement rings to glasses frames. “It is just a matter of time before these three-dimensional printers will be able to replicate an entire gun,” Israel said. “And that firearm will be able to be brought through this security line, through the metal detector, and because there will be no metal to be detected, firearms will be brought on planes without anyone’s knowledge.”

It’s a scary scenario, made all the more so by last week’s massacre at a Newtown, Connecticut, elementary school. As Israel tells it, guns made out of plastic parts by home 3-D printers might provide a roundabout path to gun ownership for convicted felons or the mentally ill. Given that a nearly identical bill was signed into law by President George W. Biush, Israel’s legislation stands a pretty good chance of passing. But it’s not entirely clear whether Israel’s bill would actual curb the kinds of activities he says it does—or, given the current state of things, whether that’s even desirable. To understand the future of printed guins, it helps to understand how it began.

The 3-D-printed guns scare began, as these things generally do, with a group of Ron Paul-loving, Bitcoin-trading twentysomethings. Last spring, Cody Wilson, a 24-year-old Ray-Ban-toting law student at the University of Texas, joined with a handful of friends from back home in Arkansas to launch the Wiki Weapons project, an attempt to, in the group’s words, “produce and publish a file for a completely printable gun,” such that “any person has near-instant access to a firearm through the internet.”

Ambitious doesn’t do it justice. Wilson et al. wanted to do for weapons what Gutenberg did for books: “This project might change the way we think about gun control and consumption,” they wrote. “How do governments behave if they must one day operate on the assumption that any and every citizen has near instant access to a firearm through the Internet? Let’s find out.”

Although Wiki Weapons is infused with Wilson’s own libertarian politics—he rails against “international kleptocrats” in a promotional video—the mission, he explains, is far removed from cold-dead-hands rhetoric. He’s never gone hunting, and, until last year, he never even owned a gun. “I kind of like seeing how the consequences of the internet affect the ‘real world’ and this kind of blending between these two kinds of spaces,” Wilson told me. “To me, that’s the fascination of it—it’s not like the worship of the gun as this totemic object.”

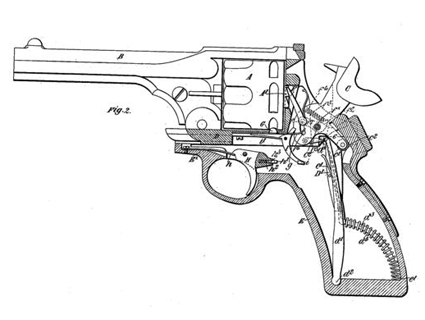

Wilson began experimenting with different prototypes; submitted to an unannounced “interrogation” from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives; and had to find a new 3-D printing company to work with after the first one backed out. In December, he showed off the fruits of his efforts—an AR-15 made from mass-produced metal parts and a 3-D-printed plastic receiver.

It lasted six shots:

The video was a hit on the internet, uniting gun hobbyists and open-society types in a collective slow-clap for the Wiki Weapon. But the gun itself—the same model used by Newtown shooter Adam Lanza—was a bit of a bust. It still faced engineering challenges (among other things: plastic melts), and Wilson had successfully printed just one part of the gun; the rest came from licensed manufacturers. It’s also cost-prohibitive: Although the price of 3-D printers has dropped over the last few years, the kind of equipment needed to produce a highly complex piece of weaponry still requires a significant investment—well beyond the $299 you’d pay for an AR-15 online.

Besides, while consumers can live with disposable razor blades, they tend to want their guns to be a bit more durable. Just take it from Wilson. “Looking at the limits of these technologies, there just doesn’t seem to be a huge market there for weak, breakable, dangerous guns,” he says. Or, put another way: “There’s, like, 300 million guns floating around this country, you know what I’m saying?”

Given the fact that the printed gun will be little more than a novelty for a handful of self-described “Rights of Man radicals,” it’s no surprise then that the Wiki Weapon is barely on the radar screen of gun control advocates like Brady Center to Prevent Gun Violence.

“Have they even been made yet?,” said Jon Lowy, the group’s legal action director, when I asked for his position. The Brady campaign has supported efforts to ban plastic guns in the past, and Lowy says he’d be open to any proposal that curbs firearm fatalities. “But,” he added, “I also think as far as general Congress and the movement we have to be very thoughtful and strategic.”

It’s also not clear whether Israel’s bill really does stop Wiki Weapons. An Israel spokeswoman, Samantha Slater, said the congressman would introduce “the same exact bill as the one that’s currently law,” except that it will be tweaked to cover “major components” of the gun, rather than just the receiver. Slater also emphasizes that the bill doesn’t take any additional steps to block the dissemination of blueprints for printed weapons parts on the internet, meaning that whether or not the bill passes, anyone with a modem will still be able to download the necessary files to make a printable gun—which is, after all, the stated purpose of the Wiki Weapons project.

Wilson says his group, which has now split into separate outfits—an intellectual property nonprofit that exists solely to distribute blueprints, and an R&D branch that’s currently seeking a gun manufacturing license—will be entirely unaffected by the legislation. He cites an exemption in the law for gun manufacturers, which he claims enables them to build plastic guns for the purpose of testing their detectability. “Basically, the way the law works is you can’t really be seen by the ATF to be in the business of manufacturing, which means in the definitions there you can’t be regularly selling this to people,” he says. “So our position there is that none of this gets sold to anyone right now—none of the printed stuff.”

But Slater, Israel’s spokeswoman, suggests that’s a nonstarter too: “If you are building one of these guns to see if it is detected by a metal detector, then you’re exempted,” she says. “But that’s not what they’re doing…the law says it’s only to test the undetectability of the firearm. I’ll leave it up to them or to you or to the reader to decide why they’re really building these weapons.”

Ultimately, though, the only opinion that matters is that of the ATF itself. And Wilson says he’s been in contact with the agency repeatedly since their initial meeting last summer. “If these are undetectable firearms, well, then they can’t produce them,” said ATF spokeswoman Ginger Colbrun. But at this point, the agency is content to wait and see where Wiki Weapons go from here.

“I can’t sit here and say ‘what if.’ [When] they actually produce something…we can certainly comment on it.”