David Bro/ZUMA

Just because you should do something doesn’t mean you ought to.

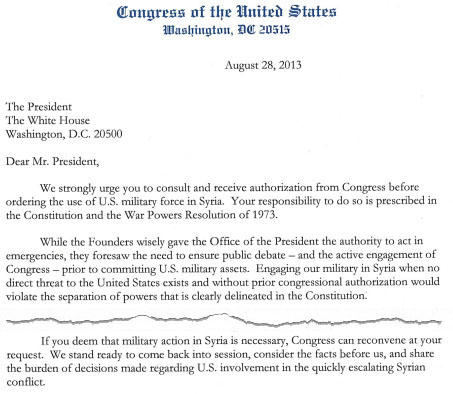

That might sum up one way of thinking about whether the United States should bomb Syria in response to the horrific chemical weapons attack presumably launched by regime forces against civilians earlier this month. The assault, which led to the deaths of 1,400 Syrians, including children, was a dramatic step over President Barack Obama’s “red line” and prompted the administration to move toward a punitive strike that would be designed not to affect the ongoing balance of power in the continuing Syrian civil war but to deter President Bashar al-Assad and his military forces from further use of chemical weapons. Immediately, a trans-Atlantic debate ensued over whether such military action would be appropriate, effective, and wise. And this afternoon—as the White House released a four-page unclassified assessment declaring that Assad regime officials “were witting of and directed the attack on August 21″—Secretary of State John Kerry made a public statement presenting the case for a limited attack.

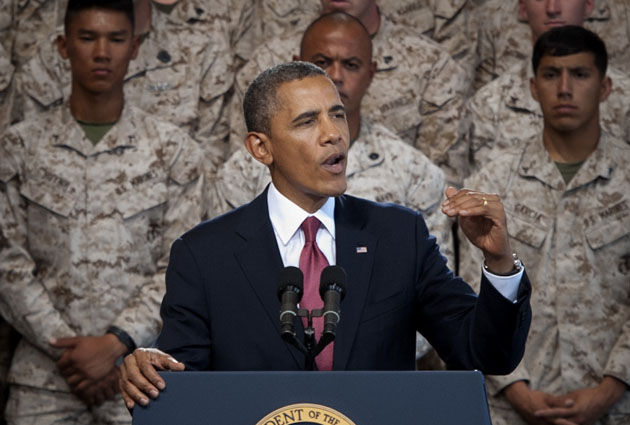

In the face of public opinion overwhelmingly opposed to US military action in Syria, Kerry argued that the United States had a humanitarian obligation to respond to Assad’s use of chemical weapons and a duty to preserve America’s credibility and that of the civilized world:

It matters to our security and the security of our allies. It matters to Israel. It matters to our close friends Jordan, Turkey, and Lebanon, all of whom live just a stiff breeze away from Damascus. It matters to all of them where the Syrian chemical weapons are—and if unchecked they can cause even greater death and destruction to those friends. And it matters deeply to the credibility and the future interests of the United States of America and our allies. It matters because a lot of other countries, whose policy has challenged these international norms, are watching. They are watching. They want to see whether the United States and our friends mean what we say.

Killing people—no doubt, some civilians would perish in a limited strike—to demonstrate credibility and toughness is not the most high-minded of arguments. Should innocents die because Obama (perhaps in a misguided move) drew a line in the sand? But there is some merit to the contention that a tyrant should not be permitted to deploy unconventional weapons with impunity.

A few days ago, I asked David Kay, the former UN weapons inspector who led the search for the nonexistent WMD in Iraq after the 2003 invasion, why he supported an attack on Assad in response to the chemical weapon massacre. He noted:

It is a terror weapon of extraordinary power…I believe if Assad gets away with showing other regimes how they can use CW to gain the upper hand in a conflict…[it] is something we should not want. Imagine if the Libyan rebellion had not occurred first, but were to be about to start. In this interconnected world we should want to maintain a ban on the use of weapons that can have large and sudden impacts. To kill 100,000 has taken Assad more than a year…Unless we now take action the wrong lesson is likely to have been learned.

It is hard to watch the videos of the victims of the chemical weapons attack and shrug. But all actions have their costs—even justifiable actions. And the question here is this: Can Obama mount a limited, targeted, and effective strike that will indeed deter Assad without drawing the United States deeper into the ongoing civil war, causing unacceptable unintended consequences (say, a high number of civilian casualties), and/or further inflaming conflicts within the region? That’s a tall order. Perhaps he and his military aides can devise such an assault and thread this needle. But Kerry, who took no questions after delivering his statement, neglected to discuss various options. Which was natural, for the administration understandably has no desire to telegraph the specifics of what apparently now is an inevitable strike (with or without any explicit approval from Congress, which is hardly rushing to vote on the matter).

In his tough-worded statement, Kerry, the onetime anti-war activist, resorted to a familiar rhetorical device. “What is the risk of doing nothing?” he asked. (George W. Bush repeatedly used similar language in the run-up to the Iraq invasion.) Yet decrying doing nothing does not justify a specific action. The Hippocratic Oath counsels: First, do no harm. A military strike would do some harm. Will the gain outweigh the harm? Obama is often adept at working through complicated calculations. But in war—and in the Middle East—intelligent calculations can look rather different after the fact.