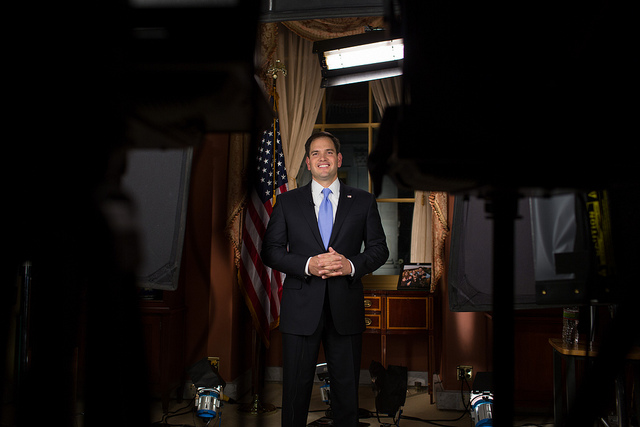

Charles Dharapak/ZUMA

In his State of the Union address last year, President Barack Obama, just weeks after winning reelection, delivered a speech with real punch. He presented a fiercely progressive agenda, and it seemed there actually might be a chance that a few items on his to-do list—immigration reform or gun safety measures—would make it through Congress, despite the continuing influence of die-hard tea partiers in the House Republican caucus. Obama forcefully declared then that he would boldly pursue important initiatives. He was making good use of postelection momentum by putting forward an ambitious game plan. It was a call to action that embodied the currents of the moment. The speech was big. A year later, Obama has downsized.

Clearly, Obama has recognized the reality that obstructionist Republicans on the Hill render big things virtually impossible. After all, the past few years have shown that they can barely keep the government open. So in this year’s State of the Union address, Obama talked about large needs, particularly boosting economic opportunity and bolstering the economy for the tough competition of this century. But he didn’t invest much in promoting grand pieces of legislation. He instead made the case for a host of policies that could nudge the nation in a better direction: tax reform that closes corporate loopholes, gun safety measures, immigration reform, patent reform, infrastructure investment, Head Start expansion, a boost in federal funds for scientific research, ending gender inequality in pay, extending unemployment insurance, curbing subsidies for fossil fuels, and a higher minimum wage for all workers. He has pushed for all of this before. And he declared that on its own—without Congress, that is—his administration would raise the minimum wage for employees of federal contractors, open new high-tech manufacturing hubs, set new standards for climate change pollutants, and initiate a program to reform job-training programs (led by Vice President Joe Biden).

Put all his executive actions together, and it can be real change that helps some Americans, but it is less sweeping than his full vision. Though Obama was in high spirits—enthusiastically defending Obamacare and fervently calling for raising wages for American workers—he did not wrap all of this in one overarching political narrative. And he let the Republicans off easy. He did chide House GOPers for voting 40 times to repeal the Affordable Care Act. And he referenced the recent government shutdown and debt ceiling showdown, noting that when political debate “prevents us from carrying out even the most basic functions of our democracy—when our differences shut down government or threaten the full faith and credit of the Untied States—then we are not doing right by the American people.” But Obama didn’t use this opportunity to focus on the reason he has to go it alone: Republicans hell-bent on disrupting the government and thwarting all the initiatives he deems necessary for the good of the nation. Even when he quasi-denounced the government shutdown, he did not name-check House Speaker John Boehner and his tea-party-driven comrades. During the speech, he even hailed Boehner, the son of a barkeep, as a symbol of the American dream.

In the past, Obama has not been shy about addressing the fundamental conflict that besieges Washington: He believes government can be used to steer the economy toward a better place and provide support to Americans in need; Republicans consider government the problem. This clash has brought Washington to a standstill—at least in terms of producing legislation that addresses the country’s priorities. Yet Obama barely called out Republicans in this speech; he did not exploit this high-profile moment to confront the obstructionist opposition. He delivered heartfelt anecdotes about Americans who need a raise or who rely on Obamacare. His tone was positive; his rhetoric was uplifting. He sought to move CEOs and citizens to action. But he did little to influence the political landscape.

It could be that Obama does not wish to antagonize Republicans, out of hope that immigration reform or tax reform might still be possible in the last years of his presidency. Perhaps he believes it would be unseemly to poke too hard at Republican legislators within their own chamber. Maybe he didn’t want to appear stuck in the GOP-created muck of the nation’s capital. He took the high road. But this speech lacked a political context. It was full of powerful arguments and powerful tales about the struggles of particular Americans. Obama’s rousing delivery surpassed the content. His tribute to Sgt. Cory Remsburg, a vet wounded in Afghanistan who was sitting next to Michelle Obama, was moving and justifiably sparked the longest and loudest applause of the evening. “Men and women like Cory,” he proclaimed, “remind us that America has never come easy.”

One can wonder exactly what that means. But there is a reason why progress in Washington is not coming easy these days—and why the lives of many Americans will remain more difficult than need be. (See the unemployment insurance dust-up.) Yet the president left this out. He was seeking to inspire but within a political vacuum. How far will his sound carry in that environment?