The 2012 London Olympics were huge for female athletes, with more women competing than ever before in Olympic history. In 1900, just 2.2 percent of Olympians were women; by 2012, that number had jumped to 44.3 percent. This week’s Sochi Games will offer even more medal stand opportunities, with ski jump including women for the first time since the Winter Olympics began in 1924.

But even while more women are competing in the Olympics today than ever, they’re “still not equal in any way,” says Eleanor Smeal, president of the Feminist Majority Foundation, a women’s advocacy group focusing on issues including sports.The modern Games have carried on a long-standing tradition of keeping women on the sidelines. Weightlifting, boxing, cycling, wrestling, and water polo all were men’s-only sports for much of Summer Olympics history, some excluding women for more than a century. The same goes for bobsled and ice hockey, which shut women out for much of the Winter Games’ 88-year run. Here’s a closer look at each Olympic sport’s track record (more after the chart):

“Every new sport has been a fight for years,” Smeal says. She notes that even ski jump—which had been the last Winter Olympic sport to exclude women—was the result of a long battle that wound up in court.

Women ski jumpers petitioned to compete in every Olympics since the 1998 Games in Nagano, Japan. (Men have been competing since the Winter Olympics began.) There were lame excuses along the way: In 2005, Gian-Franco Kasper, president of the International Ski Federation and a member of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), said that women hadn’t been allowed to participate in the Olympic ski jump because jumping from high heights year-round “seems not to be appropriate for ladies from a medical point of view.”

In 2009, an international group of female ski jumpers sued the Vancouver Organizing Committee in the British Columbia supreme court for gender discrimination. Justice Lauri Ann Fenlon agreed that the Vancouver committee was guilty of discrimination, but asking the IOC to include women’s ski jump in the Olympics fell outside of the court’s jurisdiction.

Two of this year’s female Olympic ski jumpers, Jessica Jerome and Lindsey Van—who in 2010 set the record for longest jump (105.5 meters) at Vancouver’s Whistler Olympic Park for both men and women (the world record is 246.5 meters)—were among the plaintiffs in the 2009 Vancouver lawsuit. “When it comes down to it, it’s a dick-swinging competition,” Jerome said in the documentary Fighting Gravity, which publicized the 2009 case. “It’s old-fashioned, traditional European men who have their extreme sport,” Jerome added. “They don’t want women diluting it. It’s an all-boys’ club. It’s all bullshit politics.”

Kathy Babiak, an associate professor and director of the Sport, Health, and Activity Research and Policy Center at the University of Michigan, says that in the past, excluding women from an Olympic sport made it harder for those aspiring Olympians to secure the sponsors and funding necessary to hold competitions at the international level. At the same time, the IOC requires that a sport be administered by an international organization before it can be considered for inclusion the Olympic program. “It’s a chicken and the egg problem,” she says.

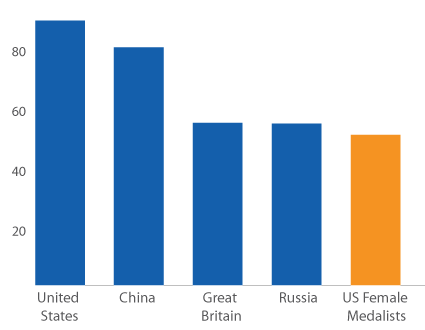

Smeal and Babiak note other persisting gender gaps. Not every national Olympic team sends women, and even for those that do, different rules may apply: The Japanese women’s soccer team and the Australian women’s basketball team flew coach while their male colleagues cruised in business class to the 2012 London Games. That year, men’s events outnumbered women’s 162 to 132. And women are often subject to a different set of regulations. In Sochi, women ski jumpers will compete in one event, the individual normal hill, whereas men will compete in three. The low share of women in leadership positions on national and international Olympic committees and international sports federations, Babiak and Smeal say, is another reason why, after all these years, women remain underrepresented in the Games.

Beyond that, they say, blatant sexism is still a serious problem, and continues to perpetuate the misconception that women aren’t as good at sports as men. Just last month, Alexander Arefyev, who coaches Russia’s men’s ski jumping team, told Izvestia: “If I had a daughter, I would never allow her to jump—it is too much hard work…Women have a different purpose: to raise children, do the housework.”

“We have to worry that the gains for women in sports, while impressive in the US and the world, nothing is really secure,” Smeal says. “We keep making gains, but we have to fight. It’s never quite equal.”

This article has been revised.