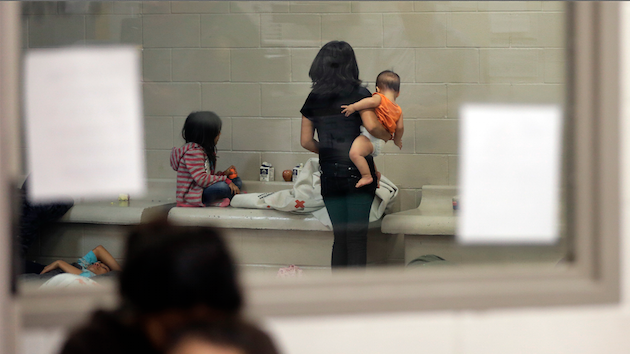

Eric Gay/AP

On Tuesday, the country’s top immigration court ruled that some migrants escaping domestic violence may qualify for asylum in the United States. The decision, from the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA), is a landmark: It’s the first time that this court has recognized a protected group that primarily includes women. The ruling offers a glimmer of hope to asylum-seekers who have fled horrific abuse. The decision has also infuriated conservatives, who claim that the ruling is a veritable invitation to undocumented immigrants and marks a vast expansion of citizenship opportunities for foreigners.

The case involved a Guatemalan woman who ran away from her abusive husband. “This abuse included weekly beatings,” the court wrote in its summary of her circumstances. “He threw paint thinner on her, which burned her breast. He raped her.” The police refused to intervene, and on Christmas 2005, she and her three children illegally entered the United States.

Before Tuesday’s decision, immigration judges routinely denied asylum to domestic violence victims because US asylum law does not protect people who are persecuted on account of their gender. The law only shields people who are persecuted because they are members of a certain race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or particular social group. Tuesday’s ruling, however, recognized “married women in Guatemala who are unable to leave their relationship” as a unique social group—giving the Guatemalan woman standing to make an asylum claim.

The conservative backlash was swift. On Wednesday, Fox News host Brian Kilmeade fumed that the decision would allow Guatemalan women “to get instant US citizenship as well as our benefits.” Speaking on Neil Cavuto’s Fox show, Steven Camarota, a member of the far-right Center for Immigration Studies, implied that the ruling would entice “tens or hundreds of millions” of women to enter the US illegally. “It’s a gross distortion of what immigration judges are supposed to do,” Carmota said.

Simona Agnolucci, a California lawyer who represents asylum seekers pro bono, refers to this as the “floodgates” argument. “It’s absurd,” she says. The BIA and US federal courts, she notes, have recognized many broad groups as eligible for asylum, including any Coptic Christian living in Egypt, any Filipino of Chinese ancestry living in the Philippines, or any gay or lesbian person living in Cuba.

Tuesday’s decision is a sharp departure from a 1999 ruling, in which the BIA found that Guatemalan women who cannot leave their marriages are not a protected class. That decision was vacated by then Attorney General Janet Reno. Rody Alvarado, the applicant in that case, won asylum in 2009, 14 years after making her plea.

“We’ve had silence out of the BIA for 14 years,” says Lisa Frydman, a director at the Center for Gender and Refugee Studies at the University of California-Hastings. “This is huge.”

The Guatemalan woman at the center of Tuesday’s ruling, identified by the court only as A-R-C-G-, does not earn asylum as a result of the decision. Instead, the BIA sent her case back down to the immigration court level. Because there is a backlog of nearly 400,000 deportation cases pending before US immigration courts, a final decision could take years.

But the implications of the decision extend well beyond her case. The ruling will affect some 300 women who have appealed their domestic-violence asylum cases to the BIA. In almost all of those cases, according to Frydman, the applicant is a Central American woman who sought asylum after being apprehended near the US border. The women then went before an immigration judge who believed the facts of their cases, but ruled that they didn’t belong to a protected group that could claim asylum.

A spokeswoman for the Executive Office for Immigration Review says that there are about 22,500 cases pending before the BIA. As a result, these women’s cases could remain in limbo for many years. But the door is now open for an immigration judge to rule someday in their favor, says Stephanie Taylor, an Austin, Texas, attorney who represents many domestic violence victims seeking asylum.

For women like Maria Sanchez, 32, this is the first good news in a long time. Sanchez (not her real name) escaped to the United States in the late 2000s. Back in Guatemala, she was the principal of her school in the town of Olintepeque. Then, several years before she fled Guatemala, she married. “He took ownership of me,” she says of her husband. He forced her to quit her job and forbid her from seeing her family. And eventually, “He was trying to kill me.”

The beatings came weekly, and without warning. Her husband might hurl dishes at her from their table, or drag her down the stairs of their home by her hair. Sanchez called the police countless times—but officers never showed up until the next morning, when they bothered to show up at all. “There are plenty of police,” she explains. “But women are seen as less.”

After two years of marriage, she escaped to her mother’s house. Her husband followed her. He tried to beat down the door, screaming that he was going to kill her. Sanchez took out a restraining order. The police refused to enforce it.

Eventually, Sanchez scraped together $7,000 from sympathetic relatives, left her daughter in the care of her mother, and took an eight-day bus ride across Mexico. She walked for four and a half days until she reached friends in Houston. Sanchez was never caught by border guards. She was working without authorization in a fast-food restaurant in Austin in 2011 when she learned about asylum from a Spanish-language radio program. Sanchez volunteered herself to the immigration court system in November of that year.

Belonging to a group that is eligible for asylum, Simona Agnolucci notes, is only one step in the asylum process. An asylum seeker also has to show that her treatment rises to the level of persecution, and that authorities in her country were unable or unwilling to protect her. The judge has to believe her story. And the applicant has to show that she was persecuted because she is a member of a particular group. That can be a tall order for victims of domestic violence. A 2012 study conducted by Frydman’s group found that immigration judges frequently find that a woman was abused for another reason—for example, because her husband was an alcoholic.

Finally, she has to actually travel to the United States. “Most women who need asylum will never get to the US,” says Bruce Einhorn, a retired immigration judge who runs a legal clinic for asylum seekers. “They just don’t. We are dealing with only a fraction of women and girls who would qualify for this type of asylum.”

On top of these challenges, the asylum process is slow. Sanchez, for example, filed her application in 2011. There’s been silence ever since. The Houston Asylum Office, which has to vet her case before she goes before an immigration judge, has yet to make a decision about her. “I’ve contacted the Houston Asylum Office countless times,” Taylor, her attorney, tells me in an email. “I’ve put in a case status inquiry with the Citizenship and Immigration Service Ombudsman’s Office. I sent a certified letter to Asylum HQ in Washington. I have not gotten a response from anyone.”

The wait has been its own kind of torture. I met Sanchez recently in her Austin apartment. The unit is sparse—decorated with a calendar from a local car insurance companies and a large, rainbow-toned poster of Jesus. Sanchez was prim, stylish, and confident. But when I asked her about her daughter, her voice becomes a husky whisper. “She’s my whole life,” she manages to say. She cries before she can stop herself.

Under the new decision, Sanchez faces better odds for her asylum application, but still more waiting.

In the meantime, immigrant rights activists are celebrating the news as a huge leap forward. “If the result is that we have a lot of people coming to our country seeking refuge, and they all have legitimate claims, and they’re all entitled to asylum and they’ve met all the hurdles to prove their cases, then we should give them asylum,” says Agnolucci. “It’s our responsibility as a nation. We passed these laws to protect people. And these people need protection.”