Beth Schlanker/ZUMA

During his acceptance speech after winning reelection, President Barack Obama thanked voters who endured hours-long lines to cast their ballots. “By the way,” he added, “we have to fix that.” Trying to make good on that promise, Obama created a presidential commission that spent months digging into the dysfunctional American voting system. One of its many conclusions was, to put it bluntly, that the nation’s poll workers suck. As the report noted, “one of the signal weaknesses of the system of election administration in the United States is the absence of a dependable, well-trained corps of poll workers.”

Poll workers, most of whom are volunteers (who typically receive a small stipend), have immense power that far surpasses their standing in the local election bureaucracy. They often make decisions about whether an individual can vote and whether that vote actually gets counted—recall the infamous Florida “hanging chads” during the 2000 presidential election recount. Often they make these decisions poorly, and the people who bear the brunt of those bad decisions are disproportionately African American and Latino, who often face chronically understaffed polling stations that lack trained workers and those who are bilingual.

If things are running less than smoothly at your polling place today, here are five reasons why the poll workers at your precinct might be clueless:

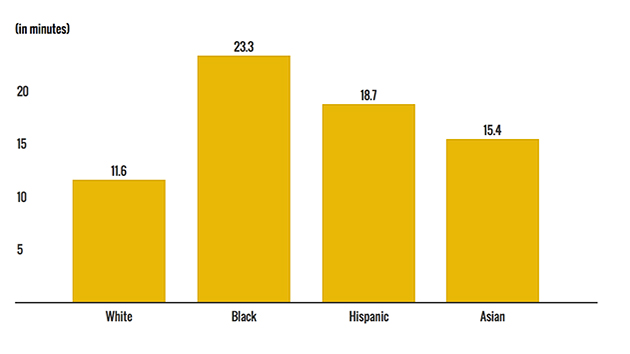

Shortages: Because the US refuses to designate Election Day as a national holiday, local election officials face chronic shortages of poll workers. That desperation leads to pretty low standards. Officials are forced to recruit people who don’t have anywhere better to be, namely retirees and marginally employed people. Poll worker shortages also mean that election officials frequently fail to get rid of people who prove they can’t do the job. And the dearth of poll workers has real consequences: A new study from the Brennan Center for Justice found that poll worker shortages were directly correlated to long lines at the polls, which tend to depress turnout, especially by minorities.

No training: There are no national standards for poll worker training. Meanwhile, the more than 8,000 election jurisdictions have widely varying requirements. Only 30 states actually mandate training. On average, a poll worker gets just two and a half hours of instruction before heading off to help manage an election.

Or there’s Philadelphia, which provides some training for poll workers but doesn’t require them to attend. “If people have been serving as poll workers for a long time they may feel they don’t need to go to training for a refresher,” says Marian Schneider of the Advancement Project, a civil rights group, noting that this can be especially problematic due to frequent changes in the law. A staffer from Advancement Project took the Philadelphia poll worker training and found that it lasted only 17 minutes, part of which was dedicated to jokes from the instructor about dead people on the voting rolls and drunk election officials. Misinformed poll workers in Pennsylvania last year turned away voters who lacked proper ID even though the state didn’t have a voter ID law in effect.

New York City requires poll workers to undergo six hours of training and pass a 25-question test on the material. Last year, the city’s division of investigation dispatched investigators to evaluate the quality of the city’s training. They discovered trainers coaching applicants on how to pass the test and outright cheating going on during the exam that went observed but unchecked.

No minimum standards: Virtually anyone with a pulse, it seems, can be a poll worker. In most jurisdictions, the only requirement is that a poll worker be a citizen and over 18. New York City investigators observed poll workers struggling to find names on the voting list on Election Day and discovered that many of the poll workers didn’t have adequate reading or English skills to locate the names, which were listed alphabetically.

Similar stories abound throughout the country, but Ohio has been a particular hot spot for poll worker problems. It’s not uncommon for large numbers of the state’s poll workers to simply fail to show up on Election Day, one cause of polling places opening late and long delays. During litigation over a contested 2010 election in Hamilton County, which includes Cincinnati, testimony showed that one poll worker sent voters to the wrong precincts because he couldn’t tell the difference between odd and even numbers.

This year, a longtime Hamilton County poll worker was indicted for voting twice in 2013—once in person and once by absentee ballot. During a hearing in her case, she claimed that it wasn’t her job as a poll worker to understand the voting rules. She said she just forgot that she’d voted the first time because she’d been having a bad day.

They’re old: No offense to the dedicated retirees who staff many of the nation’s voting places, but there are some problems with having an election system that relies almost entirely on senior citizens. More than one-fifth of poll workers are over 71, and in some places that figure is much higher. In Florida, one estimate suggests that the average poll worker is 78.

As most states have moved from paper ballots to optical scanners or touch-screen voting machines, voting technology has grown more complicated. The concern, and with some evidence, is that seniors aren’t as quick to adapt and learn the new technology. An Ohio study of elections there in 2006 found that hundreds of poll workers failed to show up on Election Day because they didn’t feel as though they could operate the electronic voting equipment.

In addition many states don’t require poll workers to undergo training before every election, so if someone has been working the polls for 40 years, it’s possible that her knowledge of election law may not be keeping up with all of the changes—and there have been a lot of them in recent years. The presidential commission on election administration urges states to change laws if necessary to bring college and high school students into the voting precinct.

The pay sucks: Most states seem to view poll workers as little more important to democracy than the average McDonald’s fry cook. Long hours and low pay are hardly an inducement for competent people to take time off from their jobs to staff a polling place. In many parts of the country, poll workers are expected to work extremely long hours on Election Day—as many as 17 hours in some places. The pay barely breaks minimum wage. In Los Angeles, it’s $80 a day. If the country wants to recruit more professional poll workers, it might just have to pay them a little better.

Given the low status accorded to poll workers, along with the lack of training and the chronic shortages, it’s really a miracle that American elections aren’t even more dysfunctional than they already are. Happy Election Day!