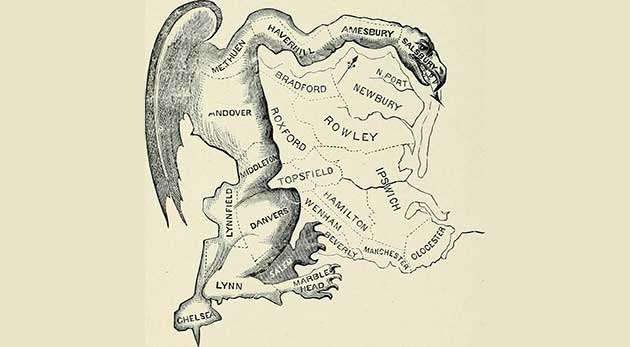

<a href="https://flic.kr/p/ovZ9v7">Internet Archive</a>/Flickr

You have to give Alabama credit for its cheek. Last year, the state’s Shelby County persuaded the US Supreme Court to find unconstitutional part of the Voting Rights Act that required certain states with histories of discriminatory election laws to get permission from the federal government before changing their voting practices. On Wednesday, Alabama will argue before the court that the same provision it helped decimate compelled lawmakers to racially gerrymander the entire state.

This convoluted case got its start after the GOP took control of both houses of the Alabama state Legislature in 2010. The Republicans then redrew the state legislative voting districts in 2012 as part of the regular redistricting process. The new plan preserved most of the state’s majority-minority districts, where black residents had political power and tended to elect Democrats—often African American ones. But state legislators also redrew the lines in a way that minimized the influence of African American voters in districts where they did not make up a majority of voters.

Here’s what happened: The population of several districts in the state had shrunk significantly. They needed to be redrawn to include more residents. But when the state legislators redrew the lines of those districts, they recast a few of them in extraordinary ways, going to great lengths to move in African Americans from neighboring districts. The result: The surrounding districts became more white, and thus, more hospitable to Republican candidates.

One district in Montgomery—nearly 72 percent black and already represented by an African American Democratic senator—needed an additional 16,000 residents to make up for population loss since 2000. GOP map makers reconfigured the district to add 15,785 new residents. Only 36 of those new residents were white. While working hard to add every possible black voter in the vicinity to the district, legislators moved white people out of the district and creatively drew the map to exclude a majority-white area of Montgomery. The impact of the segregated redistricting on this month’s election was stark: The number of white Democrats in the state Senate fell from four to one.

In 2012, a group of African American state legislators and other activists filed two lawsuits against the state challenging the redistricting plan as unconstitutional and a violation of the Voting Rights Act. (Those cases, Alabama Democratic Conference v. Alabama and Alabama Legislative Black Caucus v. Alabama, were consolidated by the federal court.) They argued that the GOP had improperly redrawn the state’s legislative districts to dilute the power of minority voters by packing them into districts already heavily populated by minorities and represented by African American legislators. The suits contended that this move deprived minority voters of the ability to influence elections in areas where they were not a majority. The suits essentially accused state Republicans of ghettoizing black voters so these citizens would not be able to help Democratic candidates defeat Republicans in nonblack districts.

Alabama has defended itself in the case by arguing that Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act required the state, during the redistricting process, to maintain the same number of majority-minority districts, with roughly the same percentage of minority voters.

Section 5 is the provision of the VRA at the heart of the Supreme Court decision in Shelby County v. Holder last year. In that case, the court invalidated another part of the law, rendering Section 5 unenforceable and freeing states like Alabama from federal oversight of its voting laws and redistricting plans on the grounds that times had changed. But the federal government could still enforce Section 5 at the time of the Alabama redistricting (a fact that now further complicates the case at the Supreme Court).

The lawsuit went to trial in 2013 before a three-judge federal district court that included one judge from the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals. That court agreed with the state, finding 2-to-1 that state legislators had not relied too much on race in redrawing the districts. But the dissenter on the panel, Judge Myron Thompson, a Carter appointee who was the second African American ever appointed as a federal judge, saw the redistricting as an illegal use of racial quotas. Thompson called the state’s use of the Voting Rights Act a “cruel irony.” He noted that even as the state was arguing before the Supreme Court in the Shelby County case that Section 5 should be struck down as unconstitutional, it was “relying on racial quotas…and seeking to justify those quotas with the very provision it was helping to render inert.”

What the Supreme Court is likely to do with the case is anyone’s guess. The conservative majority is openly hostile to the Voting Rights Act, as seen in the Shelby decision. The court also hates political gerrymandering cases. In Alabama, race is often a proxy for party, making the case even more complicated, as the state’s redistricting decisions are political as well as potentially discriminatory.

The plaintiffs have suggested that the redistricting plan in Alabama was part of a concerted Republican strategy to paint the Democratic Party as the “black” party. Their fears aren’t entirely baseless. After all, Alabama isn’t the first state to argue that the Voting Rights Act forced it to redistrict in a way that packed minorities into districts and diluted their political power. In another voting rights and redistricting case in South Carolina, a Democratic state representative, Mia McLeod, provided an affidavit attesting to a conversation she had with another member of the House about the redistricting process. She wrote:

As the conversation turned to redistricting, Rep. Viers told me that race was a very important part of the Republican redistricting strategy. Rep. Viers said that Republicans were going to get rid of white Democrats by eliminating districts where white and black voters vote together to elect a Democrat. He said the long-term goal was a future where a voter who sees a “D” by a candidate’s name knows that the candidate is an African-American candidate…Then he chuckled and said, “Well now, South Carolina will soon be black and white. Isn’t that brilliant?”

Some civil rights activists see the Alabama case as presenting an opportunity for the conservatives on the Supreme Court to further eviscerate the Voting Rights Act. Jon Greenbaum, chief counsel at the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, which filed a brief in the case, says that he worries the court could rule broadly, as it did in the Shelby case, and find that the intentional drawing of majority-minority districts in itself is unconstitutional.

This is a case when voting rights activists are acutely feeling the absence of Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, who retired from the court in 2006. O’Connor knew about the redistricting process, having once been in charge of it as a state legislator in Arizona. She was the deciding vote in favor of protecting minority voters in Shaw v. Reno, an important 1993 decision in a racially complex and contentious redistricting case in North Carolina that was decided on a 5-4 vote.

O’Connor’s replacement, Justice Samuel Alito, has displayed no such sympathy for minority voters, nor a deep understanding of the political calculations that often fuel redistricting. When the court last year found part of the Voting Rights Act unconstitutional in Shelby County, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg read her scathing dissent from the bench. While she did, Alito rolled his eyes and shook his head, showing his disdain for her view that the decision was deeply misguided.

Greenbaum thinks the Supreme Court should send the case back to the district court for further work. Voting rights law is heavily fact-based and depends on significant analysis of the local conditions on the ground that places redistricting and its consequences into proper context. Alabama did not go through such a process in redrawing its legislative map.

That’s why the Department of Justice has asked the Supreme Court to remand the case back to the federal district court for further consideration that would include the evaluation of more detailed information. But here’s the problem for the plaintiffs: That district court is incredibly hostile to their arguments. One of the judges on the panel is 11th Circuit Judge William Pryor, a former Alabama attorney general. His nomination to the court by President George W. Bush was initially filibustered by Democrats, who denounced his extreme views on abortion and his documented opposition to the Voting Rights Act. He testified before Congress in 1997—long before the Shelby County case—that Section 5 of the VRA ought to be repealed.

Given a tough choice between a conservative Supreme Court and a hostile district court, the black Alabama legislators and activists seem to be throwing their hopes in with the high court. They’ve simply asked the high court to find that the state violated the Constitution and to reverse the lower-court decision and find in their favor. Arguments on Wednesday will indicate whether they have made the right choice.