Robby Mook awoke on November 14, 2014, with a knife in his back.

At 6:01 that morning, ABC News published what it billed as a juicy scoop revealing the existence of a loyal, clubby group of Democratic staffers who called themselves the “Mook Mafia,” so named for the star political operative, who was then a leading contender to run Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign. In leaked emails, Mook, the group’s self described “Deacon,” urged his friends to “smite Republicans mafia-style.” Mook’s on-again, off-again colleague Marlon Marshall—a.k.a. “Most High Grown Ass Reverend Marlon D”—echoed his friend’s bro-ish, mock-dramatic tone. “F U Republicans,” he wrote to the list. “Mafia till I die.”

ABC didn’t name its source but described the person as a Mook Mafia list member who “does not support the idea of Mook or Marshall holding leadership roles” in a second Clinton presidential run. By leaking a cherry-picked series of emails, this source sought to knock Mook out of the running for the campaign manager job. Clinton’s campaign was still in the earliest stages, and the infighting had already begun.

But the attempt to kneecap Mook backfired. Instead, the episode illustrated the dysfunctional, cutthroat atmosphere surrounding the Clintons and underscored the need for a campaign chief who could manage the competing factions within Hillary Clinton’s universe. Embarrassing though the leak may have been, it bolstered the case for Mook, who’s known for inspiring loyalty and handling outsize egos, to take the reins of Clinton 2016.

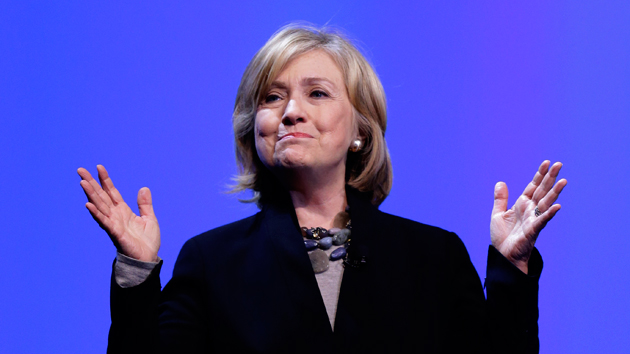

Within days, Clinton is expected to officially launch her next presidential bid—and Mook will be her campaign manager. He has the formidable task of repackaging perhaps the most widely known and picked-over public figure in modern politics and convincing a weary electorate that she should lead the country for the next four years. He will have to hold together the many tribes and fiefdoms within the Clinton community, while sidestepping—and surviving—the sort of backstabbing that felled his predecessors.

Clinton Inc. Planet Hillary. Hillaryland.

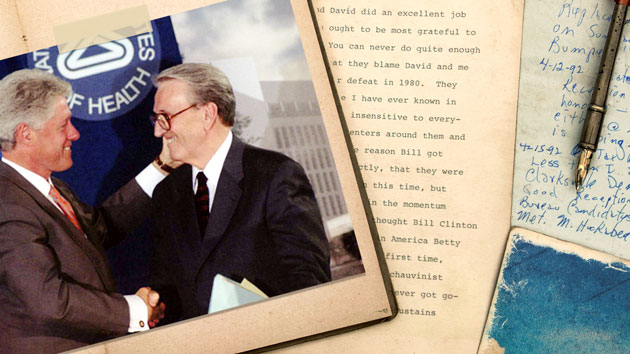

Whatever it’s called, this is the vast network of advisers, fixers, donors, lackeys, celebrity pals, old campaign hands, State Department staff, friends of Bill, friends of Hillary, and friends of Chelsea that surrounds the Clintons. “They just keep building on all of the people who are well intentioned, well meaning, extremely loyal, but all have an opinion and want to be heard,” says Patti Solis Doyle, a former aide and friend of Hillary dating back decades.

Solis Doyle was the first campaign manager of the former first lady’s 2008 presidential run. But Hillaryland’s warring factions and score-settling press leaks proved too much. In the thick of the 2008 nomination fight, Clinton relieved her of operational duties—via email and a surprise conference call—and so Solis Doyle quit.

Mook, for his part, got a sense of what it will be like to manage the Clintonworld cast of characters when he ran the campaign of Terry McAuliffe, a close friend of Bill and Hillary who was elected governor of Virginia in 2013. McAuliffe’s first run for governor, in 2009, was a disaster. He lost the Democratic nomination by 23 points. Four years later, with Mook at the helm, McAuliffe’s campaign was so focused and disciplined it caught some of the candidate’s own friends by surprise. One senior McAuliffe aide says he couldn’t recall a single leak from a campaign surrogate.

Hillary Clinton took note of Mook’s work on the McAuliffe campaign. She wants desperately to avoid the mistakes of her last race and run a low-drama campaign. Knowing this, advisers and former aides say, it’s not surprising she chose Mook. “He’s cut from a very different cloth from the bold, brash campaign managers that we hear about so often,” says pollster Geoff Garin, who worked with Mook on McAuliffe’s 2013 run. “He does not seek out the spotlight and in fact does everything he can to avoid it.”

Mook is widely known as Robby, not Robert, and at 35, he’s still boyish—handsome and clean-shaven with close-cropped brown hair. His usual uniform consists of chinos and bland dress shirts rolled up to the elbows. He couldn’t be more different from, say, James Carville, the loudmouth Ragin’ Cajun who advised Bill Clinton’s first presidential bid and now makes a living as a consultant and TV commentator. Mook rarely appears in news stories or on TV. He did not respond to repeated interview requests. He has no Facebook page. He has a Twitter account but never tweets and has forgotten the password.

Mook, who will be the first openly gay manager of a major presidential campaign, is largely unknown beyond the insular world of Democratic staffers but well liked within it. In addition to the email listserv, his loyal following—the Mook Mafia—plans yearly reunions, during which they return to a state where they once operated for a weekend of bar-hopping mixed with volunteering for a local campaign.

Mook’s friends and colleagues struggle to identify any particular policy issue that drives him. Mark Penn-style theories about key demographic groups (remember Soccer Moms?) don’t inspire him either. He’s a political nerd who lives and dies by data and nuts-and-bolts organizing. At heart, according to those who know him, he’s a mechanic. “What drives Robby is the opportunity to run a better campaign than he did the last time,” says Tom Hughes, who hired Mook for Howard Dean’s 2004 presidential campaign.

Yet in the McAuliffe race, relying on data, organizing, and a test-everything standard wasn’t enough. The secret sauce in Mook’s stewardship of the McAuliffe operation was his ability to manage and harness all the friends and well-wishers in the candidate’s orbit, from Bill and Hillary Clinton down to the lowliest county chairman. “This is where temperament comes in,” says Paul Begala, a former adviser to Bill Clinton who helped out on the campaign. “Robby corralled us, engaged us, channeled us, used us, but didn’t let us hijack all his time or the campaign.”

Think of Mook, then, as the Hillaryland Whisperer. But Mook can’t focus on Clintonworld alone. He will also need to manage the influx of Obama alums expected to join Hillary’s team and ensure that old grudges and bad habits from the 2008 campaign don’t resurface. (John Podesta, Bill Clinton’s chief of staff who went on to lead Obama’s transition team and now chairs Hillary’s presumptive campaign, might be able to help with that.)

Mook can’t eliminate all of the internal chaos that sunk Solis Doyle. He can’t reshuffle Hillary Clinton’s inner circle to his liking. His charge will be handling the egos, absorbing the sharp elbows, and putting to good use the brains, money, and connections of the ever-expanding Clinton universe.

“Hillary’s not going to dispense with Maggie Williams. She’s not going to dispense with Cheryl Mills. She’s not going to dispense with Huma Abedin just because the new boy’s on the block,” says one Democrat close to the Clintons, listing three of Hillary’s closest longtime advisers. “The new boy on the block has to learn who those people are, how to accommodate them, and, importantly, how to harness them towards the common enterprise. They all want Hillary elected, but they also all have their own turf.”

The political education of Robby Mook began at the local dump. “Everybody has to go to the dump on weekends,” he told the Vermont weekly Seven Days in 2013, in one of the few interviews he’s ever given. “My earliest memory campaigning was going to the dump to get petition signatures or handing out literature.” The son of a Dartmouth physics professor and a hospital administrator, Mook organized phone banks for the Clinton-Gore ’96 campaign as a 16-year-old. He parlayed a freshman-year bit part in Hanover High’s production of Molière’s comédie-ballet The Imaginary Invalid into a volunteer gig for the play’s director, Matt Dunne, a 24-year-old then running for his second term in the Vermont state Legislature. (Dunne says Mook’s Invalid audition was one of the funniest he’s ever seen.) A few summers later, Dunne asked Mook to launch a political action committee to raise funds for Vermont’s House Democrats. Mook was a rising college sophomore who could not yet legally drink a beer, but he won the trust of the state party’s old guard. After graduating from Columbia in 2002 with a degree in classics, Mook spent a year as the Vermont Democratic Party’s field director. Soon after the 2002 election, the state party’s former executive director, Tom Hughes, recruited Mook to join the New Hampshire staff for Howard Dean’s insurgent presidential run.

When Mook signed on in the spring of 2003, Dean, the former governor of Vermont, had just 425 official supporters—nationwide—and $150,000 in the bank. The New Hampshire team set up shop in a decrepit, asbestos-riddled mill warehouse in Manchester. “It looked like where Walter White might make meth,” one Dean staffer recalls. Hughes, who shared a Manchester apartment with Mook, says Mook arrived with a futon, a few changes of clothes, and a pair of dumbbells. Steve Gerencser, the Dean campaign’s deputy political director in New Hampshire, recalls Mook buying groceries and taking them straight to the office fridge.

At 23, “Mookie” quickly became the heart of the New Hampshire operation, former colleagues say, the rare boss beloved and respected by his charges, a workaholic who would put on a wickedly funny Scottish accent, a raconteur quick to deploy a joke or funny story at staff parties. (For Mook’s 24th birthday, his colleagues bought a life-size, stand-up cardboard cutout of him—”Mini-Mook”—looped a red-white-and-blue lei over its shoulders, and made sure it was waiting when he arrived at his party at a local sports bar.) John Hagner, who interned on the Dean campaign and worked with Mook for years afterward, recalls his old colleague’s knack for motivating those around him. When Mook asked Hagner to stay on with Dean after his internship, Hagner didn’t hesitate. “Of course I’ll quit my job,” he says, “sleep on a someone’s floor, get paid $800 a month—and be grateful for it.”

At some point, the Deaniacs in New Hampshire realized that their strategy—paying canvassers to knock on doors and make phone calls—was not going to reach enough voters to win the primary. So on a broiling hot day in July 2003, the campaign staff gathered at the University of New Hampshire for a retreat with organizing guru Marshall Ganz, a wise, crusty Harvard professor who had worked with Cesar Chavez and members of the civil rights movement. As if the yoga and team-building exercises weren’t hippie-dippy enough, the campaign held Ganz’s crash course on community organizing in a rustic yurt. Ganz told the staffers they should ditch paid canvassers promoting Dean with a cookie-cutter script and instead organize a network of volunteers who would speak to their neighbors and friends and share their personal reasons for supporting Dean. With these techniques, Ganz argued, the Deaniacs could assemble an army of local volunteers and organizers capable of turning out huge numbers of voters. The Dean campaign embraced it.

But as Mook would learn, a well-designed ground game can’t compensate for a flawed candidate. Dean’s infamous scream after the Iowa caucuses sapped the New Hampshire campaign’s momentum. Still, with the help of 4,500 volunteers working on Election Day, Dean outperformed the polls and finished second in the primary behind then-Sen. John Kerry, who went on to win the Democratic nomination.

Despite the loss, the merry band of Deaniacs would use Ganz’s teachings to reinvent Democratic campaigning. Jeremy Bird, a regional field director for Dean in New Hampshire, is one of the most sought-after consultants in Democratic politics, having masterminded Obama’s Ganz-like organizing strategy during the ’08 and ’12 campaigns. Karen Hicks, the head of Dean’s New Hampshire team, brought her grassroots chops to Clinton’s 2008 campaign. Ben LaBolt, a Dean field organizer, went on to become the press secretary for Obama’s 2012 reelection campaign. Buffy Wicks, who worked in Iowa and New Hampshire for Dean, played key roles overseeing Obama’s get-out-the-vote efforts in ’08 and ’12; she now runs Priorities USA Action, the super-PAC aiming to raise upwards of $300 million to elect Hillary Clinton next year.

The Kerry campaign and party pooh-bahs in Washington were impressed enough to hire Hicks, Mook, and Bird for the general election. But in contrast to the scrappy Dean alums, Kerry’s senior staff sneered at using volunteers to win elections. Fucking drum-circle weirdos—that’s what some Kerry insiders called Mook and his colleagues. Mook, who hated being stuck in DC crunching numbers, would wander around headquarters slapping mailing stickers onto himself and colleagues in a not-so-subtle call for getting out of the office. He spent the campaign’s final weeks in Wisconsin, where Kerry won by a scant 11,000 votes.

George W. Bush’s reelection left Mook and Bird, now roommates in a tiny studio apartment in DC’s Adams Morgan neighborhood, searching for new gigs. Bird fondly remembers sitting around one night, the two roommates buried in books, Bird whipping through fiction while ribbing Mook for reading slowly. Mook’s excuse: He was reading in Greek. His bookshelves are still stocked with books in the original Greek and histories of esoteric topics including numismatics, the study of currency.

Mook could have sought a cushy job at a political consulting firm or a senior slot on a high-profile race. Instead, he decided to run the campaign of Dave Marsden, a candidate for state delegate in northern Virginia. “You could look at it and say, ‘Ew, that looked like a backwards move,’ but in fact it was very deliberate,” says Hicks, Mook’s boss on the Dean and Kerry campaigns. “He wanted to learn to manage from the ground up and wanted experience not just from the field side but from the entire campaign.”

Marsden was a first-time candidate, but Mook treated the campaign like a presidential run in miniature. He hired five full-time organizers to cover the tiny 13-precinct district and enlisted Bird to train them. Drawing on his Rolodex of friends, congressional staffers, and campaign operatives, he threw a packed keg party fundraiser for Marsden at a mansion on Capitol Hill, though few, if any, of the paying attendees could vote in the race. By Election Day, the campaign and its volunteers had so thoroughly blanketed the district that Mook’s master list of likely Marsden supporters showed one voter unaccounted for. Forty-five minutes before polls closed, Mook drove to her home, waited outside until she returned, and confirmed that, yes, she’d voted. Marsden won by 20 points in a toss-up district. “I don’t think Fairfax County had ever seen a campaign organized on this level before,” Marsden says.

The following year, Mook managed the Maryland Democratic Party’s coordinated campaign, a thankless job plotting strategy, keeping dozens of candidates on the same page, and fundraising for Dems up and down the ballot. “It’s a small state, but they have a lot of very big players,” says Josh White, who ran Martin O’Malley’s successful gubernatorial campaign that year. “It was important to have somebody who could literally coordinate everybody and try to keep everybody happy.” In Maryland, Mook met Marlon Marshall, who became a close friend and collaborator. He was as brash and effusive as Mook was unassuming. But the two shared a healthy helping of ambition, and in early 2007, they joined Mook’s old boss Karen Hicks on Hillary Clinton’s nascent presidential campaign. Mook and Marshall were dispatched to Nevada, where they set out to build a Dean-style, volunteer-powered, grassroots machine that could deliver Clinton an early caucus win.

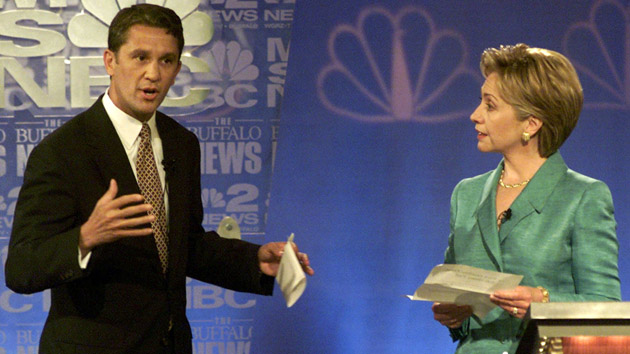

Soon after her victory in the New Hampshire presidential primary, Hillary Clinton flew to Las Vegas. It was mid-January 2008, and there was a week to go before the Nevada caucuses. Huddled with her senior staff in a private room at a steakhouse, Clinton vented her frustrations.

She felt burned, having sunk huge amounts of time and money into the Iowa caucuses only to be routed by Obama, who was proving difficult to dispatch. Now, her campaign was broke. Why would Nevada—another caucus state, one where the most powerful labor unions had endorsed Obama—be any different from Iowa? Local elected officials bitched to Clinton about her Nevada operation’s progress. “Everybody was sort of freaking out about where we were,” Hicks recalls. Bill and Hillary said they’d just as soon skip Nevada and focus on Super Tuesday, the one-day primary bonanza in February.

The task of convincing Clinton not to retreat from Nevada fell, in large part, to Mook. Seated across from Clinton and her top aides, Mook pointed to strong levels of support in the state among women, Latinos, and low-income voters. Despite being starved for funds, Mook and his team had pulled out all the stops to win over key activists throughout the state. He had even attended, unbeknownst to his staff, a Celine Dion concert at Caesar’s Palace at the request of a local LGBT rights group. (He made it back to the Nevada campaign office on Tropicana Avenue in time for the nightly check-in call.)

Hillary and Bill thought it over. In the end, they agreed: Stay and fight it out. President Clinton planted himself in Nevada for the final week, and Hillary went door-to-door.

By midafternoon of caucus day, it was clear that Mook was right; Clinton won with 51 percent of the popular vote. (Obama, however, wound up with more of Nevada’s delegates.) The media, so eager to write off Clinton’s candidacy after Iowa, described her roaring back. Rory Reid, the Clinton campaign’s Nevada chairman, invited Mook to the Clintons’ suite in the Bellagio to celebrate. Mook had spent the previous two days in a frantic final push; grimy and sweaty, he arrived last to the suite. “When everybody else was celebrating,” says Reid, a son of Sen. Harry Reid, “he was trying to wash off the results of a 48-hour organizing effort.”

Despite the Clinton campaign’s top-down approach to winning the nomination, giving more weight to national polls and fundraising totals than state-level organizing, Mook did his part to bring the Dean style of campaigning to Clintonworld. His record wasn’t lost on his foes in the Obama campaign. “He beat us three times; his footprint was on our back,” David Plouffe, one of the architects of Obama’s presidential campaigns, told Bloomberg News. “Our sense was he did the best job of anyone over there.”

Clinton’s Nevada campaign was the birthplace of the Mook Mafia, with the core group following Mook and picking up additional members as Mook bounced from one state to the next for Clinton, winning primary victories in Ohio, Indiana, and Puerto Rico. The group’s name became official in Indiana, when the mafiosi surprised Mook with T-shirts emblazoned with a Marlon Marshall mantra: “Mook Mafia: Please Believe.”

After Clinton lost the nomination to Obama, Mook spent the fall of 2008 managing Jeanne Shaheen’s Senate race in New Hampshire. But he never strayed far from the Clinton camp. After Obama tapped Clinton to serve as his secretary of state, Mook had the option of taking a job in Foggy Bottom, but decided against it. Instead, he went to the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, the party organization focused on electing Democrats to the US House of Representatives. There, Mook would learn the mechanics of congressional races from Maine to Hawaii. For his first job as political director, he recruited new candidates to run for office for the 2010 midterms, and he accumulated an obsessive knowledge of the nation’s 435 House districts. He was later promoted to a job presiding over the DCCC’s $65 million war chest for independent ad spending in 2010. He witnessed up close and personal the rise of the tea party and the shellacking the Democrats endured that year. During the 2012 cycle, when House Democrats upended pundits’ grim predictions by winning more than a dozen seats, he ran the entire organization.

Mook hadn’t yet left the DCCC when he agreed to run Terry McAuliffe’s second bid for governor. Going into Terry 2.0, Mook knew the job would require imposing discipline on the famously restive “Macker.” (“Sleep when you’re dead!” was McAuliffe’s refrain to his sleep-deprived staffers.) Despite McAuliffe’s prodigious fundraising abilities, Mook drew on the technological wizardry of the Obama ’12 campaign and the DIY culture of Dean ’04, borrowing furniture from local Democratic committees and putting staffers up at Super 8 motels; Mook’s own standing desk, one staffer recalls, was a stack of copy-paper boxes.

Mook assembled a team that included Mook Mafia members and top talent from Obama’s two campaigns. One of the first things he did was to call his old friend Jeremy Bird, fresh off Obama’s reelection, and ask which field organizers he should hire from the president’s campaign. Mook chose early on to invest in a statewide ground game—a decision that ultimately increased turnout across Virginia, especially among black voters. McAuliffe squeezed past Republican Attorney General Ken Cuccinelli, and his 3-point win marked the first time in 40 years that a Virginia gubernatorial candidate won with a president from the same party in the White House.

There was a predictable flood of “How McAuliffe Won” stories after Election Day, but they did not spotlight the operatives behind the curtain, as campaign postmortems tend to do. That was no accident. According to Brennan Bilberry, McAuliffe’s communications director, a few weeks out from the election, Mook told the McAuliffe campaign’s press shop that there would be no glorifying of staff members or dramatic retellings of the moments when the contest hung in the balance. Even after victory, he insisted, the focus should remain on the candidate.

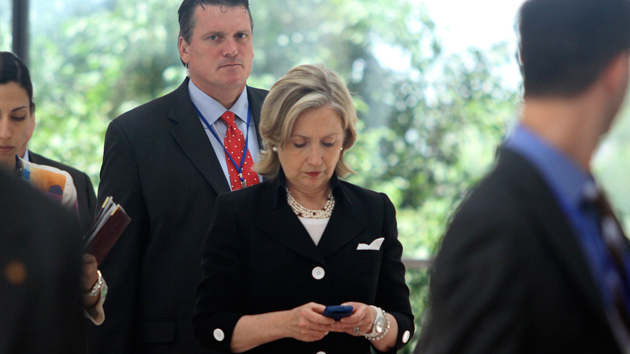

On March 10, Hillary Clinton stepped to the microphone at a hastily arranged press conference at the United Nations. A week earlier, the New York Times had reported that Clinton used a personal email when she was secretary of state, potentially in violation of federal recordkeeping rules. Her address—hdr22@clintonemail.com—was hosted on a private server registered to the Clintons’ Chappaqua, New York, home, raising concerns about the security of the sensitive emails sent and received by Clinton while at State. Of the 60,000 emails from her four years as secretary of state, she handed over roughly half to the department and deleted the remaining 30,000 or so messages, which she claimed were personal. “Looking back,” she told reporters, “it would have been probably smarter” to have used a government email account.

Politico‘s write-up of the press conference, quoting “sources in the Clinton camp,” revealed the internal divisions over how best respond to the email controversy. Several Clinton advisers had encouraged her to sit for one-on-one interviews with TV networks, rather than the harder-to-control atmosphere of a traditional press conference. Mook had pushed for a quicker, more aggressive pushback. The debate inside Clinton’s political operation, Politico noted, took on a “generational cast.” (A Clinton spokesman disputed this description of the campaign’s internal debate.)

Clinton’s campaign-in-waiting had yet to sign an office lease, and already internal deliberations were spilling out into public view. The mess indicated that Mook had a long way to go to get control of the lumbering ship he would soon be piloting.

Mook, though, is doing his best to recreate his past drama-free campaigns. He’s brought on his old friend Marlon Marshall, McAuliffe senior staffers Michael Halle, Brynne Craig, and Josh Schwerin, and a mix of respected Obama alums.

At this early stage, it’s unknown whether stocking the Clinton campaign with Mook mafiosi can bring order and discipline to Planet Hillary. No doubt, a series of contretemps, slipups, and scandals (real or trumped-up) will hit the Clinton campaign in the months to come. And in the past—with or without scandals—the competing elements of Clintonworld have always seemed to find a way to create conflict of their own.

Can Mook impose an inner calm and make sure Team Clinton focuses on one imperative: electing Hillary? “It’s very difficult,” Patti Solis Doyle says with a resigned laugh, “I will tell you that.” But should Mook succeed, nothing could be more dramatic.