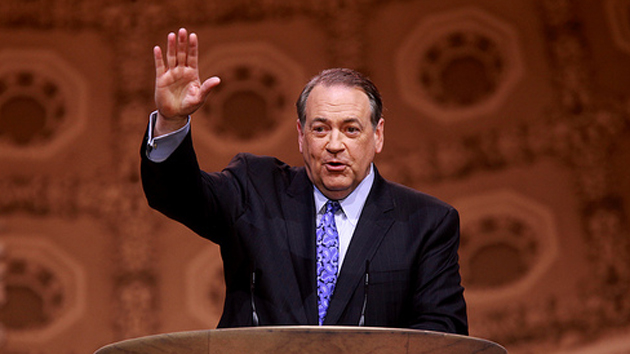

Jerry Mennenga/ZUMA

On Tuesday, Mike Huckabee made it official. The former Republican Arkansas governor and Fox News host launched his second bid for the White House in his hometown of Hope, Arkansas, vowing to stop the “slaughter” of abortion and calling for the protection of the “laws of nature” from the “the false God of judicial supremacy.”

Huckabee is joining a GOP field that’s bigger and more competitive than the one he out-hustled to win the Iowa caucuses seven years ago. The Christian conservatives who flocked to the former Baptist preacher in 2008 can now turn toward other evangelical-minded candidates in the GOP presidential race. Texas Sen. Ted Cruz is already in the hunt; former Pennsylvania Sen. Rick Santorum and and ex-Texas Gov. Rick Perry are mulling bids. But Huckabee of today is also a far different candidate than the affable ex-gov who once rocked a bass guitar while stumping with Chuck Norris (although Walker, Texas Ranger is officially on board for this campaign too). Since dropping out of the 2008 race, he’s flaunted a more combative, occasionally conspiratorial brand of politics—flirting with birtherism, advising prospective enlistees to avoid joining the armed forces until President Barack Obama has left office, and, just last month, warning social conservatives that the United States is “moving rapidly toward the criminalization of Christianity.”

By the standards of his political career, 2008 was in many ways an aberration. As he mounts a second run for the nomination, Huckabee is staying true to the kinds of red-meat issues he first entered politics to promote, in a long-shot 1992 bid for Senate against Democratic incumbent Dale Bumpers.

Huckabee, then a Baptist pastor who operated a small television station out of his Arkadelphia church, made sex and morality the centerpieces of his ’92 campaign—and he preached as fiery a message from the stump as he did from the pulpit. The novice politician let loose with eyebrow-raising tirades that occasionally put him to the right of the most fire-breathing conservatives. He endorsed quarantining AIDS patients, condemned efforts to shield homosexuals from discrimination, and called for the death penalty to be imposed on big-time drug dealers. He attacked Bumpers repeatedly as a libertine who supposedly supported giving condoms to 12-year-olds, sanctioned gay throuples, and voted to use taxpayer funds on “pornographic” art.

Huckabee’s 1992 platform was an artifact of the Moral Majority’s high-water mark. In interviews and on the stump he explained that the nation had strayed toward “selfishness and sensuality” and had been “savaged by radical groups bent on a moral and social agenda” at odds with Judeo-Christian values. “When I was in school, they passed out Gideon Bibles—today, they pass out condoms,” he said at stop after stop on the trail. In the new liberal order, Huckabee warned his hometown paper, the Hope Star, a family would consist of “three homosexual men living together.”

The gay agenda, he believed, was influencing and restricting the nation’s response to the AIDS crisis. He endorsed quarantining AIDS patients from the rest of society—a radical view even among conservatives at the time—while arguing that the severity of the epidemic had been exaggerated because gay people wielded so much political clout. The federal government should spend less money on AIDS, he insisted, and more on diseases that the afflicted had not brought on themselves, such as cancer.

“I realize a lot of people have received AIDS through blood transfusions, but AIDS is basically a lifestyle disease, and when the lifestyle is changed, the disease risk goes significantly down,” Huckabee said in one interview. AIDS advocates themselves, not taxpayers, should pony up: “Elizabeth Taylor went before Congress and made a big pitch that we needed more federal funding for AIDS. If Elizabeth Taylor would take one of the rings off her finger and sell it, she could get more money for AIDS research than the average Arkansan will make in two years of hard work. If she’s really serious about it, she’s got assets that she could dispose of. Why should she make me take money from my children’s future, and take it right off my table when she needs to cough up some of her own coin for that?”

Huckabee’s campaign literature made frequent note of Bumpers’ alleged favoritism toward gays. He attacked his opponent for supporting the Americans with Disabilities Act (because it included protections for AIDS patients) and a 1991 civil rights bill that would have prohibited housing discrimination based on sexual orientation. “Mr. Bumpers voted for all the bills which help to give homosexuals rights but takes away employers and others rights to protect themselves,” a Huckabee mailer asserted.

According to Huckabee, being gay wasn’t just a sin—it should be a criminal offense. Another Huckabee fact sheet noted that “Bumpers voted no on an amendment saying that ‘the homosexual movement threatens the strength and survival of the American family,’ and calling for enforcement of state sodomy laws,” which made gay sex a felony “crime against nature” in many states.

The ongoing conservative attack on the National Endowment for the Arts fit neatly into Huckabee’s narrative of Bumpers as a tool of the gay rights crowd. At the time, the federally funded agency was in the hot seat over a handful of artworks presenting religious symbols in ways critics considered blasphemous. Bumpers had said the art was in poor taste, but he voted not to defund the agency. Huckabee ran a radio ad accusing Bumpers of funding “pornography.” Bumpers called the ad “vile.”

“What’s vile,” Huckabee replied, “is having our tax dollars spent on photos of a man urinating in the mouth of another man, using tax dollars to fund a fictional story about the biblical character of Lazarus having homosexual liaisons with Jesus Christ before and after his resurrection, and funding for a jar of human urine in which a crucifix had been placed and entitled, ‘Piss Christ.'”

Then as now, Huckabee was a staunch opponent of abortion, a procedure he believed women underwent for superficial reasons. “Should we take a perfectly viable human being and end that human being’s life because the mother wants another semester of college or wants to play in a tennis tournament?” he asked one interviewer. And he proposed expanding the death penalty to include major drug dealers and anyone who, after committing a previous felony, shot someone with a gun—even if the shooting wasn’t fatal. “I know that’s harsh, but someone who has shot someone in the leg could easily shoot someone in the heart,” Huckabee said. (Huckabee did not respond to a request for comment on whether he still holds these views.)

Although Huckabee would later draw the ire of conservatives for raising taxes as governor of Arkansas, he took a die-hard stance on government spending. He called welfare “a new type of dependency and slavery” and warned that “the government has become a plantation system…The master is in the big house and we’re the sharecroppers out here.”

Late in the race, Huckabee discovered that his rival’s campaign had purchased more than a dozen videotapes of Huckabee’s old sermons, a potential opposition research gold mine. He suggested Bumpers watch them. “I hope he listens to the message on pornography that I presented a couple of years ago,” he said in a press release, “because then he’ll know why I feel so strongly about the way pornography degrades women and children, dehumanizes sex into animal behavior, and why I so vigorously oppose the use of my tax dollars being used to fund it.” The Bumpers campaign never did anything with the tapes Huckabee had encouraged the senator to watch.

Fire-and-brimstone Huckabee ultimately fell flat—he lost by 20 points. But the race provided a launching pad for his quick ascent up the political ladder. In later years, as he grew into a more polished politician, Huckabee became more protective of his old sermons. During the 2008 presidential campaign, reporters were told that videos of his sermons had been destroyed—or that they still existed and were open to the public but not to reporters. Huckabee, meanwhile, lasted longer than anyone expected in 2008 by crafting a reputation as a wisecracking pol who poked fun at Republicans who use “summer as a verb.”

“I think he’s the same guy who started out,” says Max Brantley, editor of the Arkansas Times, who covered the 1992 race. “He’s got a penchant for sort of cheap-shot quips. He thinks a lot of himself. He thinks he can talk himself out of anything. The main thing I still marvel at is how many people think he’s a nice guy, because he’s got a real mean streak.”

But at this point, after spending the years since the 2008 election feeding red meat to his base, the tapes may not even matter much. In just the last six months, he’s urged states to ignore a possible Supreme Court ruling on same-sex marriage and attacked Jay-Z for “arguably crossing the line from husband to pimp by exploiting his wife [Beyonce] as a sex object.” Researchers won’t have to scour church basements for dusty VHS cassettes containing his stem-winding sermons. They can just turn on the television.