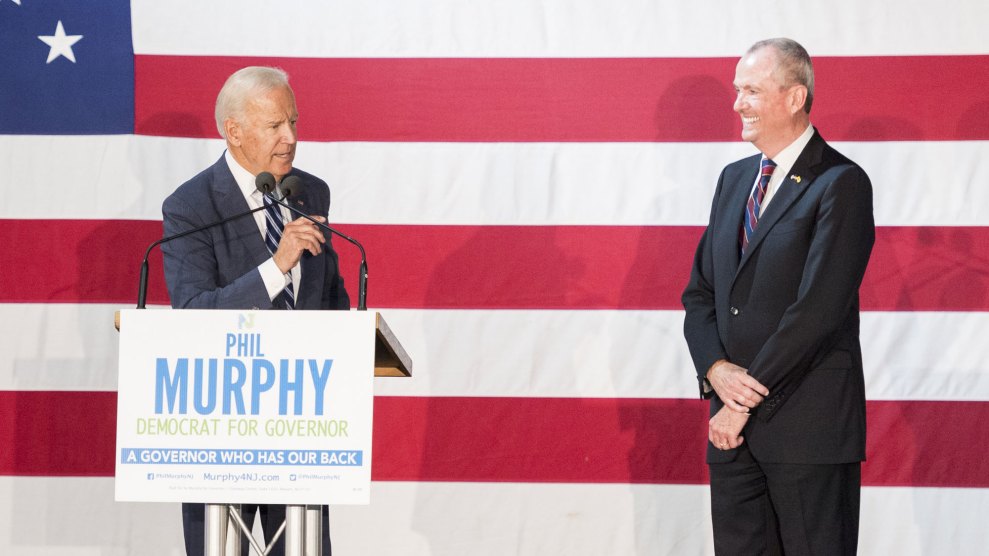

Michael Brochstein/ZUMA Wire

On Tuesday, Republican and Democratic primary voters in New Jersey will choose their nominees for what former Vice President Joe Biden has called “the single most important” election of the next three years: the race to succeed Republican Chris Christie as governor.

Biden made his declaration late last month while campaigning for Democrat Phil Murphy, the party’s likely nominee. New Jersey, despite Christie’s best efforts, is a blue state that rejected Trump by a wide margin in the presidential election, and the Democratic primary victor will head into the fall as the front-runner. (Lt. Gov. Kim Guadagno is the favorite for the Republican nomination.) Considering that national attention on the primaries has already been dwarfed by coverage of the congressional special elections in Kansas, Montana, and Georgia, as well as next Tuesday’s gubernatorial primary in Virginia, Amtrak Joe’s comments may sound like typical Biden bluster.

But despite the lack of fireworks so far, the race does tell us something about the direction the Democratic Party is heading: In 2017, even the bankers are trying to run as populists.

In the months after the November presidential election, an ascendant populist wing has pushed for the party to distance itself from its often cozy relationship with Wall Street. Trump may have stocked his administration from the break room at Goldman Sachs, but he enjoyed his greatest career success by excoriating Democrats as the party of globalist bankers. A revamped Democratic Party, in this line of thinking, would look more like the Bernie Sanders campaign, drawing its money and politics from small-dollar regular donors on a populist economic message. That’s what happened in Kansas and Montana, and to a lesser degree in Tom Perriello’s insurgent campaign for governor of Virginia.

Murphy is an awkward fit for that brand. Among his principal qualifications are that he was a former executive at Goldman Sachs and has given the state party and its elected leaders a lot of money ($1.15 million) over the years—which incidentally were the same qualifications of the last Democrat to be elected governor of New Jersey, Jon Corzine. (Murphy also served as ambassador to Germany from 2009 to 2013, a position that it not typically seen as a stepping stone to Trenton.)

But he has adopted a progressive platform that has helped insulate him from the obvious charges about his background, pushing a $15 minimum wage (nearly double what it is now), a tax on millionaires, marijuana legalization, and a state-run bank like the one proposed by Sanders. The Vermont senator never backed a candidate in the race—but his son, Levi, campaigned with Murphy.

It’s a delicate balance that another Democrat in the race, Jim Johnson, a former chairman of New York University’s Brennan Center for Justice, fought hard to disrupt. Johnson sought the mantle of Sanders-style progressivism, receiving matching public funds and attacking Murphy for his work at Goldman. In the campaign’s final stretch, he ran an ad featuring Sanders ripping into the company during last year’s presidential race. All the essential Sanders catchphrases were there: “rigged system,” “political machine,” and “dark money that poisons our politics”:

But it may have been too little too late; by that point Murphy had pulled well ahead of the pack.

In many ways Murphy’s platform, in a state with close ties to America’s capital of high finance, represents another sign of the Sanders wing’s policy momentum. (Quick: name a prospective 2020 candidate who doesn’t support a $15 minimum wage or single-payer health care.) But for a movement rooted in animosity toward the donor class, Murphy’s checkbook ascendancy highlights the gap between where the party is and where the Left still wants it to be. A populist ex-banker, after all, is still an ex-banker.