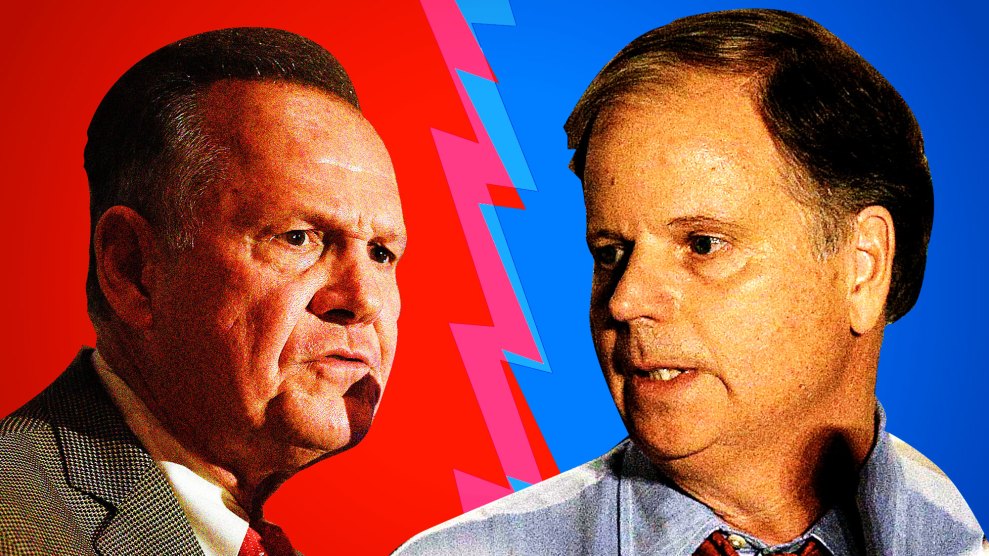

Roy Moore and Doug Jones.Photos by Brynn Anderson/AP; illustration by Mother Jones

Doug Jones was speaking to a group of lawyers in San Francisco last month about the case that has defined his career when his PowerPoint presentation arrived at an image of segregationists wielding Confederate flags. The scene took place outside a white school that was about to enroll its first black students. “If anybody ever, ever questions whether or not that Confederate battle flag is now a symbol of hate, rather than a symbol of history,” he said, “look back at these pictures [from] 1963.”

He then reached down to retrieve an old newspaper and held it up for his audience to see. It was a 1965 edition of the Thunderbolt, a racist paper put out by a group called the National States Rights Party. On the back was an advertisement for Confederate flags, which Jones read aloud: “The Confederate flag is no longer a sectional emblem. It is now the symbol of the white race and white supremacy. Fly it on your car and your house.” He set the paper down and returned his hands to the podium. “As lawyers would say, I rest my case.”

The cases for which Jones is most famous were his successful 2001 and 2002 prosecutions of two Ku Klux Klan members who had bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963, killing four young African American girls. The crime helped spur the passage of the Civil Rights Act the following year. But in Alabama, where local law enforcement was often aligned with the KKK and all-white juries exonerated anti-black vigilantes, neither local nor federal prosecutors even arrested the suspects. In 1977, the state attorney general was able to convict one of the four suspected bombers. The rest went unpunished for nearly 40 years, until Jones, the US attorney for the Northern District of Alabama, took up the case.

Now Jones is seeking to do something else that hasn’t happened in decades: win election to the US Senate in Alabama as a Democrat. Once again, it may be a matter of timing. When Jones decided to reopen the church bombing case, the resistance to prosecuting its culprits had largely dissipated. Many in Birmingham were ready to confront the city’s troubled past. (Jones was also aided by elderly witnesses who were willing to testify before they passed away and by the FBI, which reopened its own investigation of the case.) Today, Jones again finds himself making his case at a crossroads in the state’s political landscape, particularly when it comes to matters of civil rights. And he’s betting that voters will buck their strong Republican leanings to reject a candidate who’s a caricature of the state’s old—and bigoted—ways.

Jones’ Republican opponent in the December 12 special election is former Alabama Supreme Court Chief Justice Roy Moore, a horseback-riding, gun-toting evangelical who happily embraces race-based politics. Moore has twice been elected to the state’s highest judicial post, only to be removed both times for ethics violations. The first time, in 2003, was for refusing to comply with a court order to remove a 5,000-pound granite engraving of the Ten Commandments he had placed in the state Supreme Court building, in violation of the Constitution’s separation of church and state. Last fall, he was suspended from his judgeship for resisting the US Supreme Court’s decision to legalize same-sex marriage. In between his stints on the court, Moore ran a nonprofit that promoted his theocratic worldview and conservative causes, and he successfully campaigned to kill a bipartisan effort to remove pro-segregation and poll tax language from the state constitution. In the last few months, he has referred to Native Americans and Asian Americans as “reds and yellows” and declared (falsely) that athletes who kneel in protest during the national anthem are breaking the law—taking the president’s attacks on black athletes to an absurd new level.

Moore has led in most polls, but his extremism is a vulnerability. In 2012, he eked out his second election to the state Supreme Court by a 4-point margin against an unknown Democratic opponent who had entered less than three months before the election. “Roy Moore is really vulnerable,” says Wayne Flynt, an emeritus professor of history at Auburn University. “Roy Moore is a kook, and Alabamians generally consider him to be a kook.” The latest poll of the race, from Fox News last week, showed Jones and Moore tied at 42 percent apiece, but with Moore’s backers more hesitant about their choice.

The same poll found that just 26 percent of voters had a positive view of the Confederate flag, while 21 percent viewed it negatively and a majority had no reaction either way. That suggests that there may be more of an opening for Jones’ message of racial healing than was generally considered possible in Alabama. Today, support for the Confederacy—the monuments, the flag, and schools and buildings named for its leaders—has become a way for Republicans in the Trump era to demonstrate loyalty to a conservative movement that is increasingly defined by its white nationalism and activated by campaigns that play to white identity politics. Jones is offering Alabamians a different path. Just as his prosecution of the church bombers provided closure not only to the victims’ families and the black community but also to Alabama as a whole, Jones’ candidacy gives voters an opportunity to change the reputation of their state from a place that memorializes the Confederacy to one that acknowledges its past failures.

“There’s certainly a lot of rural white voters in Alabama who probably would not be taken with voting for a guy who’s got Doug’s record on civil rights,” says John Saxon, a Birmingham lawyer and longtime friend of Jones. “But I think there are people who see this as an opportunity to help change the image of the state.” A Democrat, Saxon says Republicans have approached him to confide that they will be supporting Jones. “They want his face as the face of the state and not Roy Moore’s,” he says.

It wasn’t long after the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing that the FBI zeroed in on four Klan members as suspects. But the bureau closed the case in 1968 without making any arrests. The state convicted one of the suspects, known as “Dynamite” Bob Chambliss, in 1977, but prosecutors didn’t have the evidence to convict the other three—partly because state and local officials, who were often in cahoots with the Klan, had dedicated their manpower to investigating the absurd theory that members of the black community had set off the bomb to manufacture sympathy for the civil rights movement. A law student at the time, Jones had skipped class to watch the Chambliss trial. By the time he became a US attorney in 1997, two of the remaining suspects were still alive: Thomas Blanton and Bobby Frank Cherry.

Jones enlisted one of the best prosecutors in the office and set to work. They combed all the files from the first trial and pored through library archives looking for new evidence. The investigation took three years and led to a few big breakthroughs. One was an FBI tape from a hidden recording device under Blanton’s kitchen sink, which had caught the Klansman referring multiple times to making “the bomb.” The FBI had failed to turn the evidence over to state investigators in the 1970s. Jones would play it to great effect at Blanton’s trial. The other was the discovery of crucial witnesses who had not come forward before, including Cherry’s third wife.

“The 16th Street Church bombing case was the coldest of the cold cases,” says Joyce White Vance, a prosecutor who worked under Jones at the time. “Prosecutions like this really don’t happen. And the only reason this case was prosecuted was because of Doug’s singular focus and commitment to making sure that it happened.”

“It was by no means a guarantee that he was going to get a conviction,” says John Carroll, a law professor at Samford University’s Cumberland School of Law in Birmingham. “It was a fairly risky thing that he did, which is try to reopen this cold case and try it because he certainly could have failed.” After the trials—Blanton’s in 2001 and Cherry’s in 2002—Carroll, then the dean of the law school, asked Jones to present the story of the trial to incoming law school classes. “Doug had a great way of talking about the importance of the law and how the law works for good in those sorts of instances,” he says.

Jones hasn’t shied away from discussing the bombing case and civil rights as he introduces himself to Alabama voters. On Monday, his campaign released a TV ad showing Jones speaking directly to the camera about the case. “We’ve come so far since those dark days, but we still have a ways to go,” he says in the ad. “It’s time, Alabama, to stand up for the Constitution, against violence, and for unity. And on December 12, Alabama can lead the way.” His campaign website calls voter suppression “un-American” and cites the 2015 massacre of nine black churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina, and the deadly white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, this summer as reminders that “we cannot be complacent with continued threats to equality and justice.”

But Jones’ campaign has also emphasized the need to restore respectability to Alabama politics. In less than a year, Alabama’s top officials in each branch of government have left office because of ethics violations. The powerful speaker of the state House, Mike Hubbard, was removed from office last June after being convicted on felony ethics charges; Moore left the top court a few months later for ethics violations; and the state’s governor, Robert Bentley, resigned in April and pleaded guilty to misdemeanor abuse-of-office charges for using state resources to cover up an affair with one of his aides.

The Washington Post reported earlier this month that Moore had earned more $1 million from a charity he ran for five years, despite promising not to take a salary for his work promoting Christian values. The charity’s tax filings had obscured his earnings from the IRS. “Alabamians are really embarrassed by the conduct of Republican state officials,” says Auburn University’s Flynt. “You can vote for Doug Jones even if you don’t know Doug Jones and say, ‘We’re tired of the image we have.'”

As with the bombing case, Jones’ political timing appears impeccable. Not only are Alabamians sensitive to the perception of their state as backward and racist, says Flynt, they are also fed up with their politicians. And Jones has positioned himself as an antidote to both. A TV ad his campaign released last week is called “Had Enough?” On his website, his first priority is to bring “integrity” back to politics. “The people of Alabama have been embarrassed by corruption and a string of ethics investigations and convictions of people they placed into positions of power and trust,” his website states, without naming Moore.

In addition to winning over moderates and independents looking for change, Jones’ supporters hope his record on civil rights—most notably the church bombing cases—will bring out black voters, the majority of Democrats in the state, in high enough numbers to produce a surprise victory. It may be a long shot, but bringing about convictions in a racially charged cold case seemed like a long shot at one time, too. By hammering home the message about the need to move beyond the Confederate flag and what it stands for, Jones is making an argument that his state, once again, might be ready to distance itself from its past.