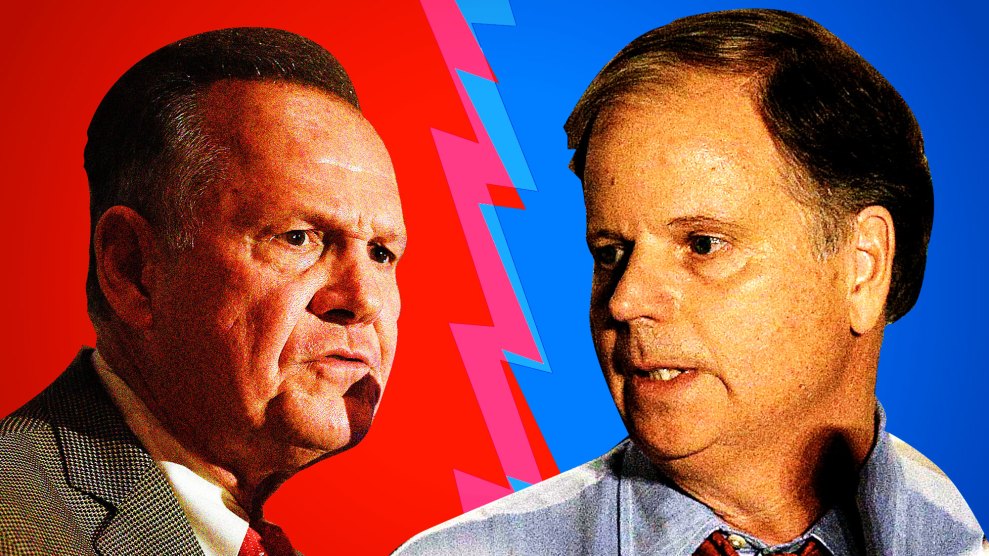

Illustration by Mother Jones

On October 21, Republican Congressman Tim Murphy formally resigned from Congress. The seven-term representative from Pennsylvania had always enjoyed strong ratings from pro-life organizations, but when the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette revealed that he had been carrying on an affair and had suggested his mistress seek an abortion, his 14 years in Washington were over.

To progressive activists who had spent the opening months of the Trump administration birddogging their congressman, pressuring him to hold a town hall on healthcare, and holding weekly rallies outside his office, the resignation kicked their efforts to replace him into warp speed. According to Mykie Reidy, an activist from Mt. Lebanon, they had already built an “army of volunteers ready to go when we had a candidate ready to do the legwork to flip the district.”

That candidate will be selected this Sunday, when hundreds of Democrats from southwestern Pennsylvania gather in a high school gymnasium to pick the nominee who will compete in a March 13 special election to fill the now-vacant 18th congressional district. The state party predicts 800 delegates, mostly precinct-level committee people, will attend to cast rounds of secret ballots until one person emerges with a majority.

It’s an unconventional process, and one that has surfaced echoes of larger debates among Democrats, fueled by ideology and identity, about how progressive their candidates should be as they fight across diverse and challenging districts to try to reclaim the House of Representatives in 2018.

“It’s going to an old–fashioned Democratic donnybrook,” says Mike Crossey, a former head of the Pennsylvania State Educators Association, and a candidate himself. Since the caucus-like system was announced, Crossey has competed with six other candidates—working the phones and flooding small party gatherings—to try to bend the ear of, and collect commitments from, as many of the small pool of voters as possible.

The district, home to just over 700,000 residents, spans four largely rural counties, starting about 90 miles east of Pittsburgh, swooping below the city and extending south and west to Maryland and West Virginia. The suburban portions include precincts where Hillary Clinton bested Obama’s 2012 numbers, but just a few miles further from the urban core, you’ll start finding territory that stretches to the ends of the state where Trump outperformed past Republicans. In 2016, he won the district by nearly 20 points. The Cook Political report has described the race “as very tough territory for Democrats. But it’s not impossible.”

Given the current warp speed of politics, March 13 may seem like a long way off, but the special election, like earlier off-cycle contests in Kansas, Montana, South Carolina, Georgia, and Virginia, will surely be read as a bellwether for Democratic prospects in 2018, especially since the district is home to many registered Democrats who voted for Trump, helping to deliver Pennsylvania’s electoral votes to the GOP for the first time since 1988.

And while the party’s selection process may have avoided a protracted primary, it hasn’t prevented division. Last week Reidy’s organization, Progress 18 PA, released a letter co-signed by coalition of groups claiming to represent thousands of progressive activists warning caucus goers not to select one potential Democratic candidate.

Her name is Gina Cerilli, a 31-year old former Miss Pennsylvania and a relative political newcomer who first took office as the chair of Westmoreland County’s board of commissioners in January 2016. Her website from that campaign boasts an endorsement from LifePac, a Pennsylvania pro-life organization that is also opposed to same sex marriage.

Cerilli did not respond to an interview request, but when when she joined the congressional race she described herself to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette as a “moderate Democrat…pro-life, pro-sportsman, and pro-union.”

“There are 70,000 more Democrats than Republicans in the 18th District, but the Democrats here vote Republican,” Cerilli noted. “They’re waiting for someone with their values so they can vote within their own party.”

Progress 18 PA takes the exact opposite view.

“Ms. Cerilli would have you believe that she is the one candidate in the field who can win this district because she is conservative and can get Republican votes. We vehemently disagree,” the letter read. “What we need to win this is a candidate who can get Democrats excited.”

While Cerilli’s platform remains a major issue for progressive activists, the letter also catalogs her missteps from the campaign trail, accusing her of deploying tactics that Progress 18 found reminiscent of their old nemesis, Representative Murphy. For example, she decided to file a lawsuit against party officials to force them to fill vacant committee positions in her home county, which could have stocked the caucus with her supporters. The letter closes by promising that its signatories will “work tirelessly” in the upcoming campaign—but only for the right person.

Last weekend, district Republicans met at a country club and selected state Rep. Rick Saccone as their candidate, picking him over two more moderate state senators. Saccone, who has boasted that “I was Trump before there was Trump,” may be best known for pushing legislation to allow schools to display the national motto, “In God We Trust.”

The Democrats attending Sunday’s nominating convention in Washington, Pennsylvania, will pick from seven candidates. Three of them had declared interest in the seat before Murphy’s meltdown: Pam Iovino, a Vote Vets endorsed former naval officer and ex-assistant secretary of Veterans Affairs; Bob Solomon, an ER physician; and Crossey, the retired educator and labor leader. After Murphy resigned, they were joined by Conor Lamb, a former Marine and federal prosecutor; Reuben Brock, a counselor and college professor; Keith Seewald, an activist and writer; and Cerilli.

Democrats in the state expect the strongest contenders to be Lamb, who comes from a prominent Pennsylvania political family, Iovino, whose campaign was well established when Murphy imploded, and Cerilli, who is counting on heavy support from Westmoreland county.

“Nobody I know in the activist community is willing to knock doors for her,” says Reidy. “We worked too hard to make this district flippable.”

Image credit: GlobalP/Getty. Illustration by Adam Vieyra.