Eighty-year-old Dennise Whitley was born and raised and still lives in Norway, a 5,000-person town in southwestern Maine where her family has resided for more than 100 years. Her grandfather and father worked in its once-thriving shoe manufacturing industry, in a factory that, like so many across New England, has closed. “And right now I’m making a Maine blueberry pie!” she tells me when we speak over the phone in August.

Whitley says that she and her family “are very good Democrats—and always have been,” even though Oxford County, part of the 2nd Congressional District, which covers nearly 80 percent of the state, is “quite Republican.” But, much like baking with the state’s prized blueberry crop, Whitley has long participated in another proud Maine tradition: crossing party lines for “many, many, many years” to vote for Susan Collins. “She’s a good Maine girl,” Whitley says of the 67-year-old Republican senator. “I tend to vote for the person who I think can get the job done.”

That tradition ends this year. Whitley’s been disappointed by Collins’ turn to “rock-ribbed Republicanism,” exemplified by her vote to confirm Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh. “I feel badly because I think she has served our country well in the past and was an independent thinker,” Whitley says. “I just am puzzled at the change.”

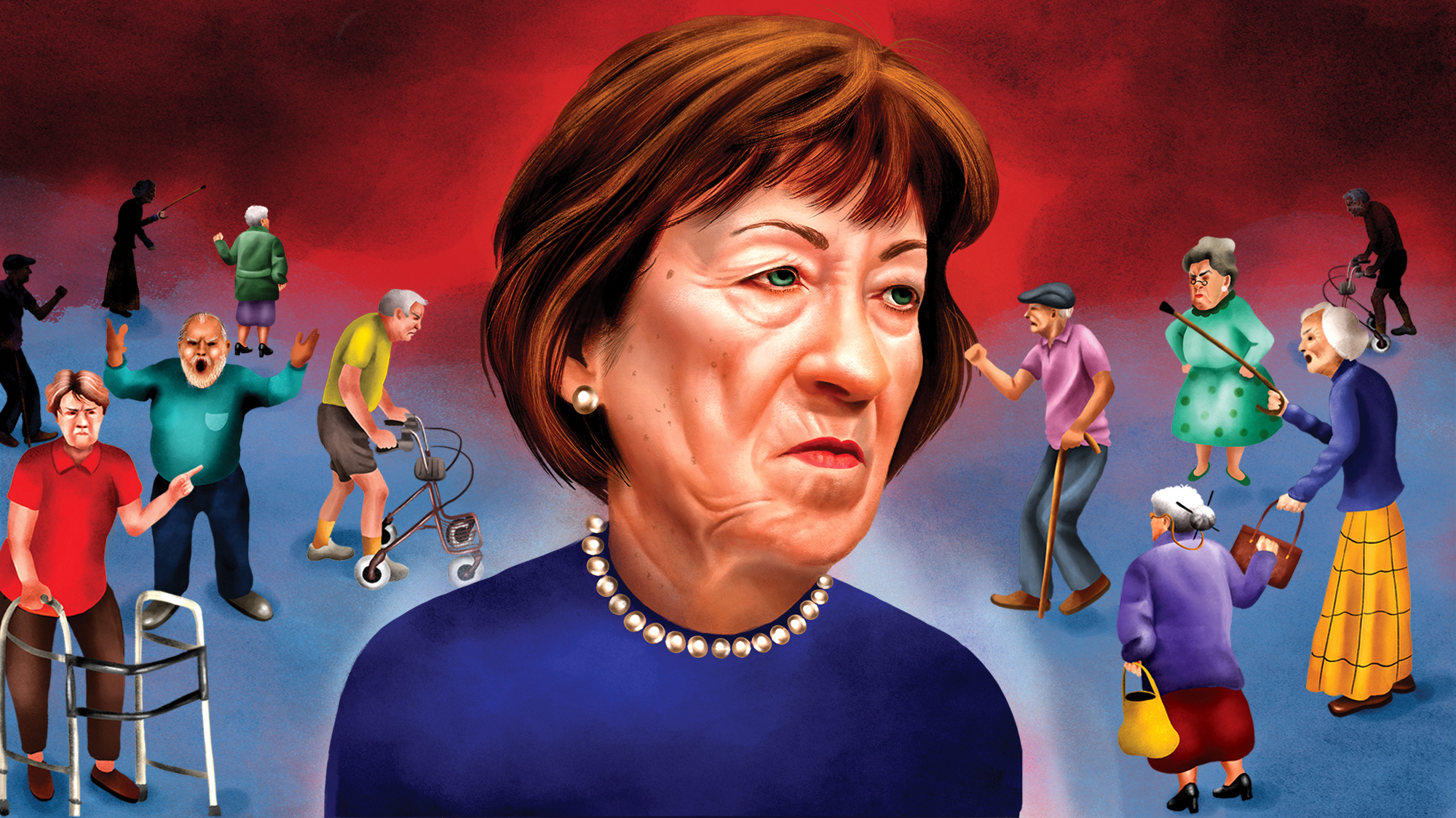

This doesn’t bode well for Collins. In each of her past four Senate campaigns, she comfortably defeated her Democratic opponents, with consistent support from her fellow Boomers and Silent Generation voters like Whitley who embody a brand of nonconformist New England moderation that favors split-ticket voting. And these voters play an outsize role. More than a fifth of Mainers are older than 65, and they reliably cast ballots. “Maine seniors aren’t only the most important voting bloc in Maine—they’re also the most informed,” says Emily Cain, the executive director of EMILY’s List, who once served as the Democratic minority leader in Maine’s State House.

If Collins loses this November, a freshly mobilized grassroots resistance can take some of the credit. But so too can Maine’s seniors, who appear to be abandoning her: While they supported her by a 20-percentage-point margin in 2014, a September poll showed them preferring her opponent by 18 points.

This election is shaping up as a referendum on whether Collins’ trademark moderation has lost its credibility. “I’m an important voice for the nation in an increasingly polarized environment,” she told the New York Times last July. “There are so few members left in the center.” She was one of three Republicans to back President Barack Obama’s economic stimulus package; she voted with Democrats to expand background checks for gun buyers after the 2012 Sandy Hook massacre; and she voted to repeal the ban on openly gay and lesbian troops. In 2016, she penned an op-ed announcing that she would not vote for Trump. In the early days of his administration, Collins seemed poised to reprise her role as a centrist when she helped Democrats sink her party’s repeated attempts to repeal Obamacare.

Overall, two-thirds of Collins’ votes have aligned with the president’s position, according to FiveThirtyEight, less than any of her Republican colleagues’. Yet she hasn’t been able to prove her independence from Trump or the GOP-controlled Senate that’s beholden to him. She voted for Trump’s tax cuts, which undercut the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate and provided the basis for an ongoing lawsuit, supported by the president, that seeks to undo Obamacare entirely. During Trump’s Senate impeachment trial, she sided with Democrats in their failed effort to bring in witnesses, but ultimately voted to acquit.

And she’s voted to confirm nearly all of Trump’s conservative—and unusually controversial—nominees, culminating in her vote for Kavanaugh, which many saw as the ultimate betrayal of her moderate bona fides. Upon the death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Collins broke with the president’s wishes and said that the Supreme Court nominee selected to replace her should be chosen by “the president who is elected on November 3rd.” Even so, progressive organizations flooded Facebook with advertisements warning that Collins will “say and do nothing of consequence” as her GOP colleagues move ahead and confirm Trump’s pick—a feat that doesn’t require Collins’ vote.

For years, left-leaning but nominally nonpartisan groups rewarded her for breaking with her party leadership, but that’s changed. Planned Parenthood, the League of Conservation Voters, the Human Rights Campaign, and Everytown for Gun Safety have endorsed Collins in the past; this year, they’ve all thrown their weight behind her Democratic opponent, Sara Gideon. Angus King, Maine’s independent senator, who generally sides with Democrats, has not endorsed Collins as he did in 2014.

At pivotal moments, Collins has met the president’s erratic behavior with belabored hand-wringing and mealy-mouthed explanations of why she’s still behind him. After his impeachment, Collins said the president’s conduct was “wrong” but that he’d learned a “pretty big lesson” and that she believed “he will be much more cautious in the future.” In mid-March, Collins criticized Trump’s “messaging” on the coronavirus and said he should “step back” from his frequent press conferences and allow health experts to educate the public. Three weeks later, she walked it back and said Trump “did a lot that was right” at the beginning of the pandemic.

But sitting on the fence may not be the remedy Mainers are looking for. “Donald Trump’s response to COVID isn’t something you can be neutral about,” says Cain of EMILY’s List, “especially when you come from a state that values independence.”

“There were a lot of challenges Maine seniors were facing even before COVID-19 that we’ve seen heightened,” says Lori Parham, AARP’s state director. Many of the state’s seniors reside in isolated, rural communities and experience food insecurity; a quarter rely on Social Security for at least 90 percent of their income. A statewide stay-at-home order helped keep the rate of infection relatively low, but it shut down meal distribution sites and it limited preventive care visits.

Older Mainers are also more reliant on the mail, often the only means of getting prescriptions in areas not served by private carriers. In July, Collins introduced a bill with Sen. Diane Feinstein (D-Calif.) to provide up to $25 billion in emergency funding to the post office to cover revenue losses resulting from the pandemic.* Yet the agency’s current debt crisis was precipitated by a 2006 law, introduced by Collins, that required it to stockpile enough money to cover 75 years of its employees’ retirement health care benefits. In late August, white-haired Mainers carrying “Don’t Mess with USPS” signs rallied outside post offices in Bangor and Portland. Melissa Berky, a 65-year-old who lives down the street from Collins in Bangor and helped organize the protest, says she’d phoned the senator to tell her to save the post office. “I said, ‘I get medications by mail.’”

Gideon has jumped on Collins for stirring up the “perfect storm” facing the post office. Her ads have slammed Collins for endangering Social Security and Medicare funding by voting for the Trump tax cut. The constant barrage of advertising has made this one of the most expensive Senate races in the country: Collins and Gideon have raised a combined $41 million, and another $41 million has been spent for and against them, a fortune considering Maine has some of the country’s most inexpensive media markets.

The broad support Trump enjoyed among seniors nationwide in 2016 has slipped this cycle, but that decline doesn’t explain what’s happening to Collins. Hillary Clinton won the state in 2016 and seniors were overwhelmingly with her. But Trump earned one of the state’s four split Electoral College votes with support from the state’s minority but ardent GOP base in the 2nd District. If Collins were to try to win back ticked-off seniors, she’d risk alienating those Trump fans. She may already have: Trump said Collins was “very badly hurt” by here statement to not support his SCOTUS nominee before knowing the outcome of the presidential election. “Her people aren’t going to take it,” he warned on Fox News.

Beyond the Supreme Court, though, Collins has fallen back on her default of avoiding a position on Trump, offering tortured logic as to why she won’t endorse anyone in the presidential race. She told the New York Times she likes Trump’s stewardship of the economy but won’t come out directly against Biden because she refuses to campaign against former Senate colleagues—exactly the sort of equivocating that has driven away Collins’ former fans.

Whitley and her contemporaries, for their part, have no problem standing up to the president. She isn’t exactly sure how her friends will vote since her usual venues for political gossip, like her regular bridge group, have been on hold for months. But her lack of intel may be a clue. “They’re smart, they’re independent,” Whitley says of her friends. “They recognize that you need to wear a mask and wash your hands.”