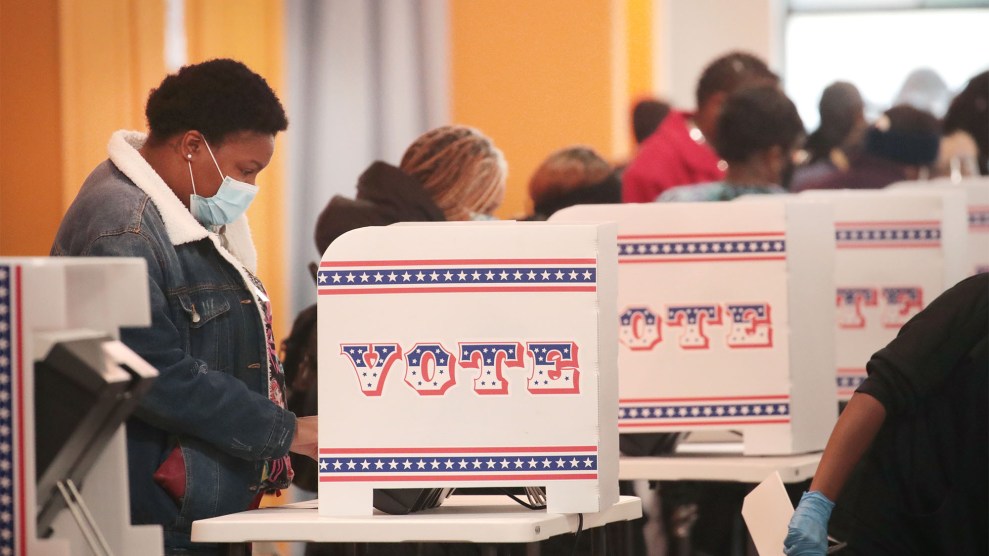

Residents vote at a polling place in the Midtown neighborhood of Milwaukee on October 20.Scott Olson/Getty Images

On March 23, the community organizer Melody McCurtis requested an absentee ballot for Wisconsin’s April 7 primary. COVID-19 was spiking in Milwaukee’s Black neighborhoods, and McCurtis was living with her mother, Danell Cross, who has an enlarged heart and high blood pressure. They worked together at Metcalfe Park Community Bridges, a grassroots group focused on increasing civic participation in one of the city’s poorest Black neighborhoods.

But McCurtis’ ballot never arrived, and Wisconsin’s GOP-controlled legislature rebuffed calls to push back the election to allow voters to cast ballots at a safer time. The city of Milwaukee was forced to cut the number of polling places from 180 to 5 because it couldn’t recruit enough poll workers, and McCurtis reluctantly stood in line for two-and-a-half hours to vote, worrying about whether she might contract COVID-19 at the polls and spread it to her family. “The experience was disrespectful to people that looked like me, to my ancestors who fought for our right to vote,” she said.

Turnout dropped by nearly 9 points in Milwaukee because of the polling place closures, the Brennan Center for Justice found, with the largest decline among Black voters. “That was a warning, and we took it as such,” says Wisconsin Lt. Gov. Mandela Barnes, the first African American to hold that position. “If Republicans could compromise people’s safety in an effort to suppress voter turnout, who knows what to expect in November?”

McCurtis and Cross had founded Metcalfe Park Community Bridges in 2018 partly in response to the 2016 election, when a new voter ID law and other GOP-passed restrictions on voting caused turnout to plunge in Milwaukee, particularly in Black neighborhoods like Metcalfe Park. “The anger that you can see in the community—how dare you try to take my vote away from me?—is why you’re seeing people coming out to vote in large numbers now,” says Cross, the group’s executive director. “We’re committed to not having that happen again.”

In 2016, there weren’t really groups like Metcalfe Park Community Bridges in Milwaukee to combat voter suppression and help Black voters cast their ballots. Now, it’s one of a handful of new groups dedicated to increasing Black engagement in the city. If Joe Biden flips the state—which Donald Trump won by fewer than 23,000 votes last election—their work will be a major reason why.

Angela Lang, the 30-year-old executive director of Black Leaders Organizing Communities (BLOC), founded the group in 2017 to focus on often-overlooked Black neighborhoods in Milwaukee. “We saw what happened in 2016 and decided we can’t let that happen again,” she told me when I visited BLOC’s headquarters last year. “We wanted to make sure people were doing intentional Black organizing on the north side of Milwaukee.” The group knocked on 173,000 doors during the 2018 election, helping increase turnout by four points in the city’s majority-Black wards and push Democrat Tony Evers to a narrow victory over Scott Walker in the gubernatorial race.

The pandemic has forced BLOC to abandon door-to-door canvassing and instead text and call voters and organize in creative ways, through things like weekly BLOC Jeopardy!, a game that answers residents’ questions about how to vote. (Evers was a guest on Friday.) “In 2016, it was really, really quiet,” Lang says. Despite the pandemic, “there’s a lot more enthusiasm this year.”

Metcalfe Park Community Bridges is one of the few groups that is still going door to door. Its volunteers and employees knock on 2,000 doors every two weeks to talk with voters. McCurtis carries a bullhorn to get the message out, and the group gives residents aid packages with food and essential items, like masks and hand sanitizer, along with information about voting.

On the first day of early voting, McCurtis took a caravan of 40 people to vote early at Washington Park Library in Metcalfe Park. So many people showed up at the library that it took McCurtis two hours to vote.

“I’ve never seen the kind of get-out-the-vote efforts I see now in Milwaukee,” says Neil Albrecht, the former executive director of the Milwaukee Election Commission. The city has 15 early voting sites, up from three in 2016, and will have its usual 180 polling places on Election Day instead of five during the primary. On Friday, early voting turnout surpassed 2016 levels, and mail voting has skyrocketed. Nearly a third of 2020 Milwaukee voters did not vote in 2016, according to Tom Bonier of the Democratic data firm TargetSmart, and these new voters favor Democrats by 61 points.

Because of Trump, COVID-19, the sagging economy, and the shooting of Jacob Blake in nearby Kenosha, “the Black community feels like it’s life or death to vote,” says Cross.

But voter suppression and the difficulty of voting in the pandemic still loom large in Milwaukee. “A pandemic is the new photo ID,” says Albrecht. Voters who lack the necessary IDs to vote may be reluctant to make a trip to the DMV. A witness signature is required for mail ballots, which can be difficult to obtain at a time of social distancing. If people have moved during the pandemic or been evicted, they must live at their current address for 28 days in order to register to vote. Postal delays have increased black voters’ skepticism toward mail voting. “We have to spend a lot of time breaking down all the different things people have to do in order to vote,” says McCurtis. “It hasn’t been an easy process.”

As a result of these barriers, which fall hardest on Black voters, turnout in Milwaukee still lags other blue areas like Madison, as well as the city’s deep-red suburbs. And the Supreme Court put up another barrier to voting last week by ruling that mail ballots must be received by Election Day, after a lower court had ruled that they were valid if they arrived within six days of the election. “When the rules keep changing, we should always be concerned someone didn’t get the memo,” says Barnes.

As of Sunday morning, Wisconsin still has nearly 180,000 outstanding absentee ballots, and the largest number, 33,000, are in Milwaukee County. Ten thousand ballots were counted in Milwaukee during the April primary that arrived after Election Day under a court order (and 80,000 overall in Wisconsin); under the new rules, these would have been thrown out. “We will lose probably thousands of votes because of that,” says Albrecht.

So in the campaign’s hectic final days, organizers like McCurtis are intensifying their efforts to urge voters to drop off their ballots or vote in person. “Everyone is counting on this election for things to change,” says the Rev. Greg Lewis, who runs a coalition of 500 faith leaders called Souls to the Polls. “And if Milwaukee comes out and votes, things will change.”