Mother Jones; Cassidy DuHon/Rhaina Cohen

Over the past year, the question of whether or not to try and have a second child has plagued me. I constantly calculate what resources I’ll have to raise two humans, and whether similar resources will be around to care for me when I’m old. This accounting, which always induces mild panic, invariably refracts a larger agita humming within me: Why do these choices, painfully boring in their mid-30s mundanity and yet personally earth-shaking, feel so narrow?

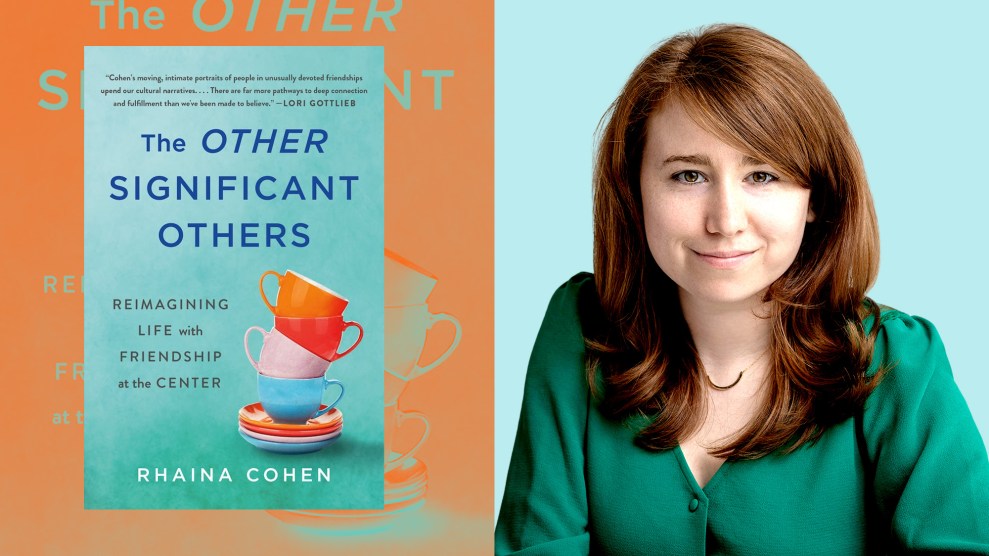

It’s this sense of constriction that drew me to Rhaina Cohen’s, The Other Significant Others, which essentially asks us to expand. Cohen specifically proposes a reimagining of adult life in such a way wherein friendship—not romantic or sexual relationships—is at the center of adult life. What possibilities suddenly become available? Now, this is not some saccharine ode to BFF-dom. Cohen reports on several real-life examples that defy convention, each carving out a unique path that reveals radical approaches to how we show up for one another. In a country so brutally hostile to caregiving, that’s nothing short of radical.

I talked to Cohen about our culture’s misguided assumptions about relationships—and how a reconsideration could unlock far more intimate ways of living.

Safety nets and caregiving are fundamentally broken in America. Do you see other significant others, these deep relationships with people who aren’t romantic partners, as possible solutions?

Caregiving is a huge thread throughout the book and in a way, it can be a possible solution. Right now, we have a pretty limited idea of how we give and receive care. This shows up with the people that I profiled who are caring for each other outside the bounds of what is typical. Their lives are enriched by the fact that they have a friend in the position society typically reserves for romantic partners.

These friendships provide both support and create opportunities for people to have care, these rare caregiving relationships, these meaningful relationships that they wouldn’t otherwise. The same goes for illness and having somebody by your bedside in situations like cancer treatment. Having more potential for people to step into caregiving roles gives us many more options for support in a way that’s not marriage or bust.

Why do you think American society is so fixated on the notion that the nuclear family is paramount to caregiving roles? Many cultures outside the US aren’t like this.

So much of this dates back to the mid-20th century and how our country was physically reconstructed to support the nuclear family household. I think about my brother and sister-in-law who live in a household with their two-month-old and my sister-in-law’s parents. The only reason that my brother would ever live in this multi-generational setting is that his wife is from China, and she grew up in a household where she had her grandmother and there was an expectation that her parents would live with her once she had a kid. This idea is incomprehensible for a lot of people because they are giving up total control and privacy over their household; there are more adults to negotiate with. And it’s anathema to people who have been made to privilege and prioritize privacy and the semblance of control. The question for many parents in untraditional settings like this is whether it’s worth it to give up control over what their kid is exposed to maybe get these other forms of support. Not everybody wants to make that bargain. We also don’t have a lot of models that show us how to do it.

I relate to this a lot, especially as a Korean American. Living with my parents is certainly a possible future. There are a lot of things to consider with that setup.

What I noticed when I have talked to people about these sorts of situations, including my own relatively unconventional living situation, is that people are quick to identify the drawbacks of unconventional decisions. What people miss, though, is that when they decide on the conventional, they often overlook the drawbacks.

I live in a household where I live with my husband and two of our friends and their two kids. Let’s think about this situation from my friend’s perspective. Yes, there will be influences from adults they can’t totally control. But they and their kids are also receiving things in return, such as deep relationships with people that otherwise probably wouldn’t exist in the same way. Intentionality is key here. When people are climbing the ladder of life, I don’t think they’re necessarily confronting, in a real way, various tradeoffs or truly articulating their values.

Why do you think that is?

I don’t fault anybody for conventional choices. But oftentimes, these choices are constrained. So it can be helpful to flip things upside down because it’s often clarifying. Why do we choose what we choose? Is this what we would choose if we had a real choice? One of the big things I’m trying to do with this book is to show how constrained some of our choices are. And by showcasing people who have paved different paths, I want to demonstrate what it means to make a true choice with true alternatives.

What recommendations do you have for people who want to foster these kinds of deep relationships with their friends but don’t necessarily know where to start?

Having cultural models for these kinds of relationships can be very helpful. Broad City, Full House, Grace and Frankie are a few good examples. And it’s important to have open discussions about what people want.

One of the wonderful pieces of feedback I’ve been getting is how much people want this but they don’t think other people want it. There’s a disconnect between what people want for themselves and what they think other people want. One way to reconcile that is to try to have deliberate conversations about what your ideal world would look like and what your friendships would ideally look like. I interviewed someone who asked a great question: What is the fullest version of a friendship? That’s different from making every friendship into a partnership, but rather sitting with someone to decide on what they want this friendship to be. Being vulnerable and being willing to open up conversations like this is immensely helpful.

People are feeling isolated and feeling isolated in their isolation, and no one wants to be rejected. So it does take leaps of faith and vulnerability to pursue deeper partnerships.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.