Joel Martinez/The Monitor/AP

On January 6, Gabriel Garcia—a first-generation Cuban American and former member of the Proud Boys—livestreamed his attempt to breach the Capitol. “How does it feel being a traitor to the country?” he screamed at police officers as he entered the building. Once inside the Rotunda, Garcia yelled, “Nancy, come out and play!” as insurrections searched for House Speaker Nancy Pelosi.

Garcia was subsequently found guilty of two felony charges related to his actions that day. But a year later, he seemed unrepentant: In fact, Garcia joined a press conference in Miami to commemorate the anniversary of the insurrection.

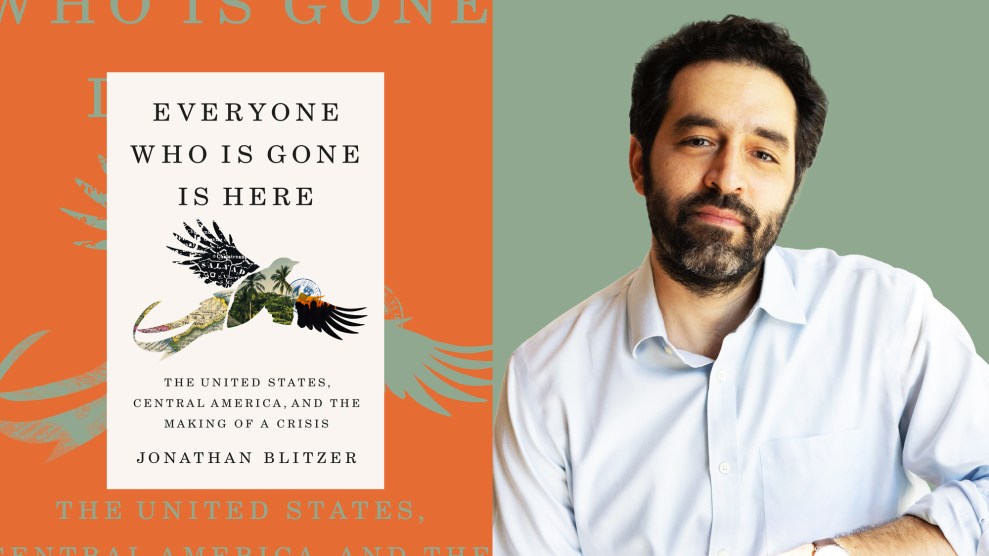

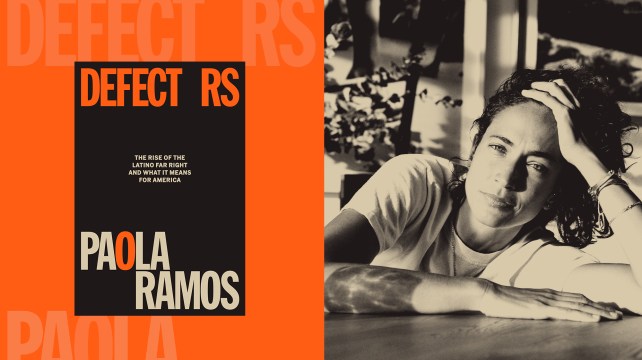

He wasn’t the only Latino there. As journalist Paola Ramos documents in her new book, Defectors: The Rise of the Latino Far Right and What It Means for America, the occasion drew members of the “parental rights” group Moms for Liberty and the Proud Boys, and many Latinos. “If we don’t agree with the left, or the media’s bias,” Garcia said at the press conference, “we get called ‘white supremacists’ or ‘racists.’ There’s nothing racist about a guy called Gabriel Garcia.”

In Defectors, Ramos, a contributor for Telemundo News and MSNBC, investigates the “quiet radicalization of Latinos [that] is taking place across the nation in plain sight” and the factors behind the pull. Dispelling common stereotypes of Latinos in the United States as a unified bloc of voters allegiant to the Democratic Party and progressive values, Ramos writes that “to understand our history, which tells us that Latinos can carry white supremacist tendencies—whether they’re racially coded as white or not—is to understand that Latinos can easily act as the majority we are supposed to reject.”

I spoke with Ramos about how cultural assimilation can lead to nativism, the deep-seated anti-immigrant sentiment among some Latinos, and the shortcomings of dismissing a small but growing segment of that population as an anomaly.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clairty.

In the book, you write that “mythologies about Latino identity ignore the very real political and cultural changes brought about by the MAGA movement’s efforts.” Why is it an oversimplification to attribute Republicans’ and Trump’s inroads with Latinos in recent elections to just a “rightward shift” from 2016 to 2020?

I think the whole point of the book is that I try and force people to understand the story beneath the numbers, which is, to me, this idea that there are larger cultural, historical, and psychological forces that are driving a small—but I believe a growing number—of Latinos towards extremism and Trumpism. When you zoom into that, you see that there is this racial baggage, colonial mindset, and political traumas that we carry with us. I think what we’re seeing now is the way in which Trumpism is revealing those elements.

What are the main influences you identified as driving a small but significant number of Latinos to the right?

I structured the book in three ways: tribalism, traditionalism, and trauma. Tribalism I refer to as internalized racism. Our story is also part of the story of having been colonized. With that came a caste system, colorism. What I refer to as traditionalism is the way in which colonization enforces patriarchal and binary norms. What does that mean in today’s culture wars? What does that mean in today’s debates around Christianity and Christian nationalism? And then what I refer to as trauma is understanding the very complicated relationship that we have with communism, but the way also that we’ve had very complicated relationships with strongmen rule and authoritarianism and the history of the United States’ involvement in Latin America. All of those ‘T’s’’ manifest in very complicated ways in American politics. I think the easy story is to mark us off as this liberal, progressive, united bloc. But it’s actually a messy story, particularly when you understand the darker parts of our history.

How has the United States’ legacy of spreading American exceptionalism in Latin America impacted the country’s own ongoing “battle with democracy”?

The way that in this country defeating communism became synonymous with patriotism, with the ultimate definition of what it means to be an American…

From the way that we’ve been involved in Cuba, Nicaragua, Chile, El Salvador, where there were these very concerted efforts to overthrow, in some more violent and other more subtle ways, elements of socialism. Now what we see is not only a diaspora of Latinos that flee from those countries, but also a United States government that reinforces the idea of Democrats being synonymous with communism, which is part of the Trumpism strategy. There’s this tendency to go back to those wounds that are very familiar to Latinos. You’re fleeing communism? Well, communism can also happen in the United States. This idea that when democracy feels somewhat messy in the United States, then you resort to the strongman rule.

I do think the majority of people that I’ve interviewed do actually have very traumatic experiences with the past. I don’t want to underestimate that. Where the manipulation happens is on the Republican Party side, where they’ve been able to really master is a way of exploiting that trauma through the spread of mis- and disinformation wars. They’ve also found a way to exploit that racial tension by creating this idea that there’s a crisis at the border, or fearmongering criminal talk.

The first chapter of your book focuses on anti-immigrant sentiment among some Latinos in the United States, including a first-generation Mexican immigrant turned border vigilante, Anthony Aguero, who sees recent migrants as people who are vastly different from him—even a threat. A recent Axios poll shows an increase in the percentage of Latinos who say they support building a border wall and ramping up deportations. What did you learn from your reporting about what leads some Latinos to embrace nativism?

There’s a blurry line. We can be minorities, but we too can perpetuate racism. Latinos, particularly the more generations are in this country, are not immune to nativism. The more we assimilate, the more we conform to American principles and the idea of “otherizing” is a real force, whether you’re Latino or whether you’re white. That’s why something like the great replacement theory is so forceful and is so potent. The dynamic of nativism at its core is this idea that culture is being threatened by the “other.” A lot of Latinos, no matter how American you are, have to work twice as hard to prove belonging. You’re third or fourth-generation Latino, but there are always these sentiments of not belonging or being “otherized” by fellow Americans and there’s this constant wrestling with the idea of having to prove yourself.

For a small group of Latinos, that journey can become very painful to the point that you can end up with some Latinos like Anthony Aguero who become fervent anti-immigrant vigilantes along the border because they’re pulled by those two notions of proving that they belong and proving that they are not like the “others.” It’s very easy to become radicalized just to prove that you are not them.

Anti-immigrant sentiment is so powerful, pervasive, and infectious that even newly arrived immigrants can sort of lean into that.

Do you think extreme anti-immigrant policies—like SB 4 in Texas, which in some ways is reminiscent of SB 1070, the “show me your papers” measure in Arizona, and Proposition 187, which denies undocumented immigrants access to public benefits in California—can lead to backlash and reverse this trend?

This book is about a small but growing segment of Latinos. I do still think that the majority of Latinos are still more united.

I think what’s interesting about this moment is that I see it as a cultural reckoning. Is this the election where you have some Latinos continuing the numbers of 2020? And if that is the case, then perhaps parts of the white vote and the Latino vote are a lot more similar than not, and part of what’s driving that similarity is the issue of immigration.

But I still believe that the majority of Latinos are united by this solidarity as having immigrant roots. I think of the way that Arizona turned blue because of the trauma that so many of those immigrant children experienced as they were seeing their parents being deported by Sheriff [Joe] Arpaio. I still do believe that is at the core of what will drive the majority of Latinos this November—this idea that in the face of someone like Donald Trump, Latinos have more in common against that image than not.

We’re in an interesting moment where there’s still a little bit of distance between the border and some Latinos, between Donald Trump and some Latinos—but the moment that it starts to creep into their own reality where potentially someone can knock at your door and racially profile you no matter how long you’ve been in this country, then perhaps we’ll start to see a shift.

You argue that the Democratic Party has failed to see Latinos in their totality. What should Democrats do differently in 2024?

I do think that the Democratic Party, at least this time, is mobilizing earlier. They’re doing outreach a lot earlier than they have in previous years, they’re paying a lot of attention to Spanish-language media.

I always go back to: don’t dismiss the small shifts, the surveys, and the polls so quickly. Don’t dismiss these rightward shifts as anomalies or outliers. Because that means truly dismissing Latinos, once again, as really complex humans that carry a lot of complicated history, pasts, and traumas into this country. It goes back to this idea that Latinos are a monolith. Dismissing it can lead to results like we saw in 2020 when Trump did over 10 points better than he did in 2016.

I hope that we can start to break that apart and have hard conversations about what it means to be an extremely complex, misunderstood community in this country.