It was a chilly December morning when I got to the gates of Angola prison, and I was nervous as I waited to be admitted. To begin with, nothing looked the way it ought to have looked. The entrance, with its little yellow gatehouse and red brick sign, could have marked the gates of one of the smaller national parks. There was a museum with a gift shop, where I perused miniature handcuffs, jars of inmate-made jelly, and mugs that read “Angola: A Gated Community” before moving on to the exhibits, which include Gruesome Gertie, the only electric chair in which a prisoner was executed twice. (It didn’t take the first time, possibly because the executioners were visibly drunk.)

Besides being cold and disoriented, I had the well-founded sense of being someplace where I wasn’t wanted. Angola welcomes a thousand or more visitors a month, including religious groups, schoolchildren, and tourists taking a side trip from their vacations in plantation country. Under ordinary circumstances, it’s possible to drive up to the gate and tour the prison in a state vehicle, accompanied by a staff guide. But for me, it had taken close to two years and the threat of an ACLU lawsuit to get permission to visit the place.

I was studying an exhibit of sawed-off shotguns when I heard someone call my name. It was Cathy Fontenot, the assistant warden in charge of PR. Smartly dressed in a tailored shirt and jeans, a suede jacket, and boots with four-inch heels, she introduced me to a smiling corrections officer (“my bodyguard”) and to Pam Laborde, the genial head spokeswoman for the Louisiana department of corrections who had come up from Baton Rouge to help escort me on my hard-won tour of Angola.

Everyone was there except the person I had come to see: Warden Burl Cain, a man with a near-mythical reputation for turning Angola, once known as the bloodiest prison in the South, into a model facility. Among born-again Christians, Cain is revered for delivering hundreds of incarcerated sinners to the Lord—running the nation’s largest maximum-security prison, as one evangelical publication put it, “with an iron fist and an even stronger love for Jesus.” To Cain’s more secular admirers, Angola demonstrates an attractive option for controlling the nation’s booming prison population at a time when the notion of rehabilitation has effectively been abandoned.

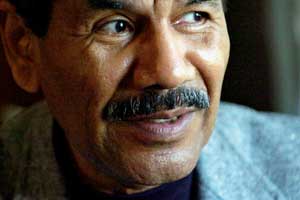

What I had heard about Cain, and seen in the plentiful footage of him, led me to expect an affable guy—big gut, pale, jowly face, good-old-boy demeanor. Indeed, former Angola inmates say that prisoners who respond to Cain’s program of “moral rehabilitation” through Christian redemption are rewarded with privileges, humane treatment, and personal attention. Those who displease him, though, can face harsh punishments. Wilbert Rideau, the award-winning former Angolite editor who is probably Angola’s most famous ex-con, says when he first arrived at the prison, Cain tried to enlist him as a snitch, then sought to convert him. When that didn’t work, Rideau says, his magazine became the target of censorship; he says Cain can be “a bully—harsh, unfair, vindictive.”

“Cain was like a king, a sole ruler,” Rideau writes in his recent memoir, In the Place of Justice. “He enjoyed being a dictator, and regarded himself as a benevolent one.” When a group of middle school students visited Angola a few years ago, Cain told them that the inmates were there because they “didn’t listen to their parents. They didn’t listen to law enforcement. So when they get here, I become their daddy, and they will either listen to me or make their time here very hard.”

Another former prisoner, John Thompson—who spent 14 years on death row at Angola before being exonerated by previously concealed evidence—told me that Cain runs Angola “with a Bible in one hand and a sword in the other.” And when the chips are down, Thompson said, “he drops the Bible.”

Who is the man who wields so much untempered power over so many human beings? I wanted to find out firsthand—but when I requested permission to visit the prison and interview Cain, back in 2009, Fontenot turned me down flat. Cain, she said, was not happy with what I had written about the Angola Three, a trio of inmates who have been in solitary longer than any other prisoners in America. Two years and much legal wrangling later, I was here at Fontenot’s invitation, ready to see the Cain miracle for myself.

Burl Cain has friends in many places—a vast network of contacts and supporters from Baton Rouge to Hollywood. There has been talk in Louisiana of him running for office—maybe even for governor. But no position could ever be so secure, and no authority so complete, as what he already has.

Cain, now 68, was raised in Pitkin (population 1,965), about 90 miles due west of Angola; he began his career at the Louisiana Farm Bureau, then became assistant secretary for agribusiness at the Louisiana Department of Public Safety and Corrections, which runs a number of prison plantations. He became warden of the medium-security Dixon Correctional Institute in 1981 and landed at Angola 14 years later. One official bio notes that “to escape the pressures of running the nation’s largest adult male maximum security prison, Cain enjoys hunting and traveling around the country on his motorcycle.”

Cain’s brother, James David Cain, served in the Louisiana Legislature for more than two decades. Burl Cain himself was until this year the vice chairman of the powerful State Civil Service Commission, which sets pay scales for state workers. Corrections is big business across the nation, but nowhere more so than in Louisiana, which has the highest incarceration rate in the world, keeping 1 in 55 adults behind bars. Angola is one of the largest employers in the state, with a staff of about 1,600 and an annual budget of more than $120 million; it is also a huge agricultural and industrial enterprise, with a network of customers and suppliers that depend on the warden’s good graces.

Until 2008, the department of corrections, which oversees the state’s prisons, was headed by Richard Stalder, who once worked for Cain. Today, its second in command is Sheryl Ranatza, who previously was Cain’s deputy warden. She is married to Michael Ranatza, executive director of the Louisiana Sheriffs’ Association. (The sheriffs have a direct interest in prison policy in Louisiana because the state effectively rents space in local jails—at premium rates—to house “overflow” inmates who can’t be fit into Angola and other prisons.) Together, the Angola warden and the department of corrections have long been “a political powerhouse in Louisiana,” says the Southern Center for Human Rights’ Stephen Bright. “[They are] sitting on top of all this power. Governors who come along are afraid to touch them.”

But Cain’s reputation has reached far beyond Louisiana. Shortly after taking the reins at Angola, he gained a national audience through a 1998 documentary about the prison, The Farm: Angola, USA, which won the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance and was nominated for an Academy Award. Soon Cain found himself interviewed by an admiring Charlie Rose and profiled in Time, which noted his quest to “give the 5,108 hopeless men on this former slave-breeding farm hope.” A follow-up to The Farm was released in 2009 (PDF), with Cain as the central character.

“Convict Poker” at the Angola Prison Rodeo. Photo: Mike SchreiberCain has also had an open-door policy for Hollywood. Parts of Dead Man Walking, Out of Sight, and Monster’s Ball were filmed on the prison grounds, and more recently, William Hurt spent a night there to prepare for his role as an ex-con from Angola in The Yellow Handkerchief. As Fontenot proudly told me, Forest Whitaker recently visited to prep for narrating a two-hour documentary on the prison’s hospice for Oprah’s new network. Even parts of the recent Jim Carrey film I Love You Phillip Morris, about two men who fall in love in prison, were filmed at Angola. “All the extras we were using were lifers, real killers,” costar Ewan McGregor bragged. (Cain drew the line, though, according to one Christian blogger, at allowing a gay sex scene to be filmed in the prison.)

“Convict Poker” at the Angola Prison Rodeo. Photo: Mike SchreiberCain has also had an open-door policy for Hollywood. Parts of Dead Man Walking, Out of Sight, and Monster’s Ball were filmed on the prison grounds, and more recently, William Hurt spent a night there to prepare for his role as an ex-con from Angola in The Yellow Handkerchief. As Fontenot proudly told me, Forest Whitaker recently visited to prep for narrating a two-hour documentary on the prison’s hospice for Oprah’s new network. Even parts of the recent Jim Carrey film I Love You Phillip Morris, about two men who fall in love in prison, were filmed at Angola. “All the extras we were using were lifers, real killers,” costar Ewan McGregor bragged. (Cain drew the line, though, according to one Christian blogger, at allowing a gay sex scene to be filmed in the prison.)

With Cathy Fontenot at the wheel, talking a mile a minute, our SUV sped through Angola’s expansive grounds. At 18,000 acres, the prison covers a tract of land larger than the island of Manhattan. Surrounded on three sides by the Mississippi River and on the fourth by 20 miles of scrubby, uninhabited woods, it is virtually escape-proof.

With its proximity to the river, this is prime agricultural land, made up of five former plantations and named for the country of origin of the slaves who once worked its fields. Today the prisoners, three-quarters of whom are black (PDF), still work the land by hand, earning between 2 and 20 cents an hour.

Angola’s agribusiness operation grows cash crops like cotton, corn, and soybeans, as well as fruits and vegetables. In addition to working the fields, inmates tend to Angola’s hundreds of beef cattle, its prize Percherons and quarter horses, and the dogs it breeds for law enforcement. (In addition to raising bloodhounds, the Angola kennels have experimented with crossing German shepherds and black wolves.) Prisoners also make license plates and vinyl mattresses and fashion toys for charity.

Fontenot crossed one levee after another, rolling off facts and figures and telling little stories about points of interest as we flew past. In 1997, she told me, a flooding Mississippi came close to breaching the ramparts, but they kept the water out with teams of inmates sandbagging, Warden Cain working by their side. We passed a herd of horses, which at Angola are used not only by officers riding guard over prisoners in the fields, but also to pull wagons and plows, replacing gas-guzzling tractors. Angola is working very hard to go green, Fontenot said. It is also highly entrepreneurial, with ventures such as the Prison View Golf Course bringing in extra funds at a time of budget cuts. They were, she said, considering a pet-grooming service and an Angola-branded clothing line. As we zipped down the road, we passed a big tour bus filled with visitors.

We also passed the 10,000-seat arena where Angola’s famous prison rodeos are staged each spring and fall, drawing some 70,000 people. The rodeo is famed for such events as “Convict Poker” (in which four inmates try to remain seated around a card table while being charged by a 2,000-pound bull) and “Guts and Glory” (where inmates vie to snatch a poker chip hung around the horns of an angry bull). Daniel Bergner, who spent a year at Angola researching his powerful 1998 book God of the Rodeo, observed that the crowd’s reaction was “electrified, exhilarated, the thrill of watching men in terror made forgivable because the men were murderers. I’m sure some of it was racist (See that nigger move), some disappointed (that there had been no goring), and some uneasy (with that very disappointment).” Even so, he writes, “many people were not laughing, were too bewildered or stunned by what they had just seen.”

Outside the arena, inmates sell arts and crafts, along with crawfish étouffée and Frito pies for the benefit of various inmate organizations: the Lifers Association, the Forgotten Voices Toastmasters group, Camp F Vets, and dozens of Christian groups. The rodeo was originally conjured up by the inmates, but it is now a centerpiece of Cain’s PR operation. Bergner wrote that in Cain’s first year at Angola, he entered the arena in “the closest thing he could find to a chariot”—a cart pulled by the prison’s Percherons, in which he circled the ring before the opening prayer.

One thing I learned when attending the rodeo a year earlier (it was the only way to get into Angola without Fontenot’s permission) is the vast difference in the way various groups of inmates live. Most of the men who work the booths are “trusties.” They live in open dorms or group houses, hold the most coveted jobs, move around with some degree of ease, and in some cases even have limited contact with the public. A few trusties are trucked out to keep up the grounds at the local school, while others tend to the homes and yards of B-Line, the small town inside the prison gates that is populated by Angola’s staff, many of them third- or fourth-generation corrections officers. (Angola officials have military ranks; collectively, they are sometimes still referred to by their historical name, “freemen.”)

About 700 of Angola’s 5,200 prisoners are trusties. Another 2,800 are “big stripes,” who work in the fields and factories under armed supervision. The remaining 1,500 are confined in cellblocks—some in the general population, some in 23-hour-a-day lockdown, some in punishment units. A word from the warden can make the difference between life in a “trusty camp” with a decent job and contact visits, and life in a six-by-nine isolation cell.

A little farther on was the main prison, surrounded by layers of razor wire shining bright in the sun. “Hiya,” Fontenot called out to the inmates as our entourage swept down the central walkway. “How ya doin’?” “Good morning,” they responded. She put her arm affectionately around the shoulder of one man, asked another about a personal problem. She came off as part country-western princess, part girl next door, and entirely in charge.

By most estimates, including Fontenot’s, at least 90 percent of Angola’s prisoners will die here. In Louisiana, what are effectively life sentences are now doled out not only for murder, but for anything from gang activity to bank robbery. The Angolite has reported that in 1977, just 88 men had spent more than 10 years in the prison. By 2000, 274 men had spent 25 years behind bars, and in 2009, 880 Angola inmates had spent 25 or more years inside. Sixty-four men had been locked up for more than 40 years.

Today, 3,660 men—70 percent of Angola’s population—are serving life without parole, and most of the rest have sentences too long to serve in a lifetime. “It is not too far of a stretch to claim life without parole as another form of capital punishment,” writes Lane Nelson, the magazine’s star writer (who recently received clemency). “[It is] slow execution by incarceration. Decades of segregation can numb a prisoner’s soul until he becomes devoid of an earnest desire for the joys of freedom.”

Warden Cain has gone on record as favoring the possibility of parole for those who achieve “moral rehabilitation.” Nick Trenticosta, a death-penalty attorney who currently represents 15 prisoners at Angola, says, “He knows there are individuals at Angola he believes are rehabilitated, and he believes they should be released. I think he is very frustrated by the sentencing laws in the state [and] the whole process of pardon and parole because of its political nature.”

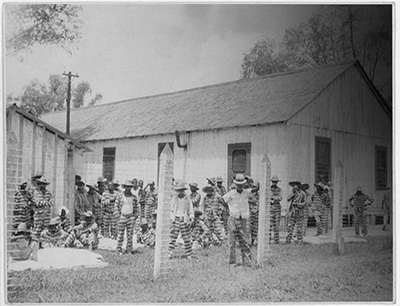

“Leadbelly in the foreground,” reads a notation on this photo by folklorist Alan Lomax, who came to Angola in 1934 to record the blues great. Photo: Library of CongressAs it stands, Cain and his staff confront an aging and increasingly infirm prison population, which is why some of Angola’s best-known programs deal with easing old age and death in prison. The prison even operates a hospice, founded and staffed by inmates, that houses men judged to have fewer than 18 months to live. When these men die, if no relatives come to claim the body, they can count on an inmate-crafted coffin, a decent funeral, and delivery, via horse-drawn hearse, to their final resting place at Angola’s Point Lookout Cemetery.

“Leadbelly in the foreground,” reads a notation on this photo by folklorist Alan Lomax, who came to Angola in 1934 to record the blues great. Photo: Library of CongressAs it stands, Cain and his staff confront an aging and increasingly infirm prison population, which is why some of Angola’s best-known programs deal with easing old age and death in prison. The prison even operates a hospice, founded and staffed by inmates, that houses men judged to have fewer than 18 months to live. When these men die, if no relatives come to claim the body, they can count on an inmate-crafted coffin, a decent funeral, and delivery, via horse-drawn hearse, to their final resting place at Angola’s Point Lookout Cemetery.

Five miles into the plantation, we arrived at death row. A central control room led to a series of tiers, each marked by a locked door and color photos of the inhabitants, 83 in all. Guards patrol the tiers day and night, looking for potential suicides.

We walked past a plastic nativity scene to get to the death house, which contains the cells where inmates spend their final hours, saying goodbye to loved ones and having their last meals. In the death chamber sat a flat, padded leather gurney with “wings” where the condemned man’s arms would be outstretched to receive the needle. Fontenot pointed out where Warden Cain would stand, near the man’s left hand, and described how he would motion for the execution to begin.

Cain’s first execution, he told the Baptist Press, was done strictly by the book. “There was a psshpssh from the machine, and then he was gone,” Cain recalled. “I felt him go to hell as I held his hand. Then the thought came over me: I just killed that man. I said nothing to him about his soul. I didn’t give him a chance to get right with God. What does God think of me? I decided that night I would never again put someone to death without telling him about his soul and about Jesus.”

By 1996, in a Diane Sawyer special about an Angola execution, Cain said that putting a prisoner to death was “so complex I can’t even answer…I came here with an opinion about a lot of things. Today I don’t have an opinion about hardly anything.”

Attorney Nick Trenticosta says that in his view, Cain treats death-row prisoners better than wardens at most other prisons: “It is not that these guys had super privileges. But Warden Cain was somewhat responsive to not only prisoners, but to their families.” Trenticosta recalls Cain demurring before one execution, “All I wanted was the keys to the big house. Not this.” The lawyer offers a picture of a man torn between the duty to kill and the faith that makes him question that duty—a dilemma he seeks to resolve, perhaps, by giving prisoners the promise of a heavenly life before the state snuffs out their earthly one.

Chapels are all over Angola, and the main one, which seats 800, was a key stop on our tour—just as it is for visiting preachers from around the country. Gathered there waiting for us was a group of inmate preachers, who spread the good news at the five houses of worship in Angola (a sixth is under construction) and at other prisons throughout the state. On occasion, they even have the opportunity to preach in the outside world. I asked the inmates whether Warden Cain had to approve what they did; one said they answered only to “Him” and pointed skyward. For a while, we listened to a former country-western bandleader play gospel on the famed Angola organ, donated by a close associate of Billy Graham. As we began to leave, one preacher raised his hand to Cathy, smiled broadly, and said, “We did good for you.”

It had taken me a while to figure out what bothered me about Cain’s religious crusade at Angola, beyond a healthy respect for the separation of church and state. My grandfather, a Methodist minister, was an evangelist of sorts, so this wasn’t an altogether foreign world to me. And I’ve seen a lot of good come out of faith-based programs—which, particularly in prison, fill the void created when lawmakers nationwide slashed funding for rehabilitation. In 1994, for example, Congress dealt a crushing blow to prison education by making inmates ineligible for higher-education Pell grants. Prison college programs, which had proved the single most effective tool for reducing recidivism, disappeared almost overnight. In Louisiana today, 1 percent of the corrections budget goes to rehabilitation.

The imbalance “makes no rational sense from a prison management point of view,” says the David Fathi, who heads the ACLU’s National Prison Project. “But unfortunately it makes political sense for the next election.” As a result, he says, “the religiously inspired programs are pretty much all there is.”

According to estimates in the Christian press, some 2,000 of Angola’s inmates have been born again since the arrival of Cain—who has described his own religious persuasion as “Bapticostal”—and 203 have earned B.A. degrees in Christian ministry at the “Bible college,” an extension program operated by the New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary that is the only route to earning a college degree at Angola.

Besides the prison seminary, Angola’s major religious institution is the Louisiana Prison Chapel Foundation, which has raised at least $1.2 million to dot the prison’s grounds with houses of worship. Franklin Graham, Billy’s son, reportedly donated $200,000 to build one of the chapels, continuing a longstanding relationship with Angola. (Inmates crafted the coffin in which Billy Graham’s wife was buried in 2007, and they are building one for Billy himself.)

Franklin Graham wrote about one of his visits to preach at the prison under the title “Freedom for the Captives.” It’s a phrase drawn from Luke 4:18-19, where Jesus announces that God “has sent Me to proclaim freedom to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to set free the oppressed, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.” It’s not hard to see why this would be an appealing message for men who will never again be physically free.

But for my grandfather, personal redemption was inseparable from social justice. Cain’s brand of Christianity, in contrast, serves in large part as an instrument of control—and the warden has little patience for those who don’t get with his program, including other Christians. In 2009, the ACLU of Louisiana filed suit on behalf of Donald Lee Leger Jr., a practicing Catholic who had sought to take Mass while on death row. He alleged that Cain had TV screens outside his cell turned up full blast and tuned to Baptist Sunday services. Prison officials destroyed a plastic rosary sent to Leger from a nearby diocese. When Leger continued to file grievances requesting Mass, he was moved to a tier of ill-behaved inmates and finally put in the hole for 10 days. The ACLU also represented Norman Sanders (PDF), a member of a Mormon Bible study course, who was denied books from Brigham Young University and Deseret Book Direct, sources of Mormon publications. (Cain told the Christian magazine World that other religions are welcome to set up programs at Angola “as long as they’re willing to pay for it. Let them all compete to catch the most fish. I’ll stand on the bank and watch.”)

An attorney representing another prisoner told me that the inmate had been disciplined because he had not bowed his head during prayer. The prisoner also alleged that inmates who don’t participate in church services will have their privileges revoked, while those who attend will get “a day or two off from the field, a good meal, and other goodies” such as ice cream. (Some help themselves to further goodies: In a recent scandal, several inmate ministers were investigated for allegedly bribing guards to let them have sex with visitors who came for special banquets.)

Historic photo of Angola Landing. Photo: Library of CongressStan Moody, a onetime prison chaplain in Maine who has met with ex-Angola prisoners, believes that “Cain is without question a committed Christian” who “cares about the downtrodden and disadvantaged in a way that’s sadly missing in prisons across the US.” But he questions pushing religion onto a “literally captive” audience, especially in exchange for better treatment. What Cain seems to be creating at Angola, Moody warns, is an atmosphere of “imposed Christian values” designed to put “notches on the old salvation belt.”

Historic photo of Angola Landing. Photo: Library of CongressStan Moody, a onetime prison chaplain in Maine who has met with ex-Angola prisoners, believes that “Cain is without question a committed Christian” who “cares about the downtrodden and disadvantaged in a way that’s sadly missing in prisons across the US.” But he questions pushing religion onto a “literally captive” audience, especially in exchange for better treatment. What Cain seems to be creating at Angola, Moody warns, is an atmosphere of “imposed Christian values” designed to put “notches on the old salvation belt.”

With those who resist salvation, Cain takes a somewhat different approach—as the men known as the Angola Three found out. When they came to Angola in 1971 for armed robbery, Herman Wallace and Albert Woodfox were Black Panthers, and they began organizing to improve prison conditions. That quickly landed them on the wrong side of the prison administration, and in 1972 they were prosecuted and convicted for the murder of a prison guard. They have been fighting the conviction ever since, pointing out (PDF) that one of the eyewitnesses was legally blind, and the other was a known prison snitch who was rewarded for his testimony.

After the murder, the two—along with a third inmate named Robert King—were put in solitary, and Woodfox and Wallace have now spent nearly four decades in the hole—something Cain has suggested has more to do with their politics than with their crimes (King was released in 2001 when his conviction in a separate prison murder was overturned). In a 2008 deposition, he said Woodfox “wants to demonstrate. He wants to organize. He wants to be defiant…He is still trying to practice Black Pantherism, and I still would not want him walking around my prison because he would organize the young new inmates. I would have me all kind of problems, more than I could stand, and I would have the blacks chasing after them.”

Wallace’s and Woodfox’s lawyers have pointed out that the two men, now in their sixties, have had a near-perfect record for more than 20 years. In response, Cain argued that “it’s not a matter of write-ups. It’s a matter of attitude and what you are…Albert Woodfox and Herman Wallace is locked in time with that Black Panther revolutionary actions they were doing way back when…And from that, there’s been no rehabilitation.” Wallace has said that Cain suggested that he and Woodfox could be released into the general population if they renounced their political views and embraced Jesus.

I asked Fontenot about the Angola Three, and she told me matter-of-factly that they just hadn’t played by the rules. Anyway, Wallace and Woodfox had recently been shipped off to other prisons in the state system. I asked about solitary confinement. The prisoners in what Angola calls “closed cells” had everything they needed, she said. It was like having a little apartment.

The Angola three are not the only inmates who claim they have suffered under Cain. Back in 1999, a group of five inmates took two guards hostage and killed one of them during an attempted prison break. Both then-Corrections Secretary Richard Stalder and Warden Cain came to the scene, and after learning of the guard’s death, Cain, according to news reports, sent in a tactical team that killed one inmate and wounded another. Nine years later, as the state prepared to try five prisoners for the guard’s murder, 25 inmates who were not involved in the escape attempt testified to what happened next.

Transcripts of their pretrial statements suggest that as prison officials tried to extract information or confessions, Angola became what one attorney described as “Abu Ghraib on the Mississippi.” Prisoners told of being beaten with fists, batons, bats, sticks, and metal rods. “You’ve got these grown men crying,” one said. Several inmates said they were thrown naked and without bedding into freezing solitary-confinement cells, denied medical care, and threatened with death if they refused to sign statements that had been prepared for them. The events prompted an FBI investigation, and the state of Louisiana eventually agreed to settle with 13 inmates who filed civil rights lawsuits. But there was no admission of guilt, and no reprimand for Warden Cain.

Even in normal times, Angola maintains a punishment unit known as Camp J, which combines extreme isolation and deprivation—prisoners cannot have any personal items and are fed a block of ground-up scraps known as “the loaf”—and is plagued by suicide attempts. There are “things that the mind can’t handle,” one former inmate told me. “I guarantee you that today, somebody tried [suicide] in Camp J.”

Certain accusations against Cain go beyond his treatment of prisoners. Shortly after he took over as warden, in 1995, he was implicated in a scandal involving a company that used Angola prison labor to relabel damaged or outdated cans of milk and tomato paste. There were allegations of kickbacks, and of retaliation against a prisoner who wrote letters to federal health officials. Both Cain and Corrections Secretary Stalder were held in contempt of court (PDF) for withholding documents, and Cain was warned to stop harassing the whistleblower.

In another episode, the Baton Rouge Advocate reported that in 2007 a grand jury in Baton Rouge subpoenaed documents involving the prison’s various businesses, as well as the Angola State Prison Museum Foundation (headed by Sheryl Ranatza, the Cain protégé who is now deputy secretary at the department of corrections) and the Angola Prison Rodeo, whose proceeds were once put into a fund for prisoner expenses such as funeral trips, TV, and the law library, but are now used to maintain the arena and build prison chapels. Cain is chairman of the committee that runs the rodeo, and he founded and sits on the board of the prison chapel foundation.

The FBI also has been investigating Prison Enterprises, the state outfit that runs all farming and industrial operations in Louisiana’s prisons, a probe that has led to several indictments; last October, a contractor named Wallace “Gene” Fletcher pled guilty to defrauding Louisiana taxpayers of some $170,000.

In 2004, Angola Rodeo producer Dan Klein went to the FBI with a complaint that Burl Cain had forced him to contribute $1,000 to the Chapel Fund. Cain said at the time that Klein made the contribution without any pressuring, and the warden himself has not been named in any of the indictments.

Daniel Bergner also says he was pressured to pitch in for one of Cain’s pet projects while writing his book on Angola: Though he initially had broad access to the prison, partway through his reporting Cain asked him to help pay for a new barn for his wife’s dressage horses, which he said would cost about $50,000. When Bergner demurred, Cain made a straight pitch: In return for arranging a “consultancy” payment for Cain, Bergner would get continued access. Bergner refused, whereupon Cain began demanding editorial control over the book and finally barred Bergner from the prison. Bergner only got access again after going to court.

After more than a year of trying to get into Angola, I too turned to a lawsuit. In March 2010, the ACLU agreed to represent me on a First Amendment claim arguing that to keep government information from a reporter merely on the basis of what he’s written is an infringement on press freedom. My attorneys asked for a listing of visitors the prison had welcomed in the previous year (not counting the everyday tourists). Without hesitation, Angola provided a 14-page list that included Miss Louisiana, the comedian Russell Brand, the Dixie Dazzle Dolls (a children’s beauty pageant group), various groups of high school and college students, judges, representatives from gospel groups and film teams, scouts looking for film locations, criminal justice students, a former member of the Colombo crime family, a French attorney. Members of the media included a journalist from Switzerland; “Neal Moore, citizen journalist, who was canoeing the Mississippi River”; and a producer getting ready to film a “future movie/documentary on finding happiness.” My attorneys dispatched one more letter to Cain urging him to grant me a visit. There was no response. But a month later, as the ACLU prepared to file suit in federal court, Fontenot wrote to them, inviting me down for a tour.

Aerial view of Angola prison, 1998. Photo: USGSIn his memoir, Wilbert Rideau writes about how tightly Cain controls his messaging—a practice that had grim consequences for the Angolite, once known for its investigative reporting. At a time when even outside journalists encountered increasing barriers to access at prisons nationwide—it’s almost impossible now to interview an inmate, or even a staffer, at many state and federal prisons—the Angolite staffers found their calls monitored and their stories censored. “The only information coming out of Angola,” Rideau says, “was what Burl Cain wanted the public to know.”

Aerial view of Angola prison, 1998. Photo: USGSIn his memoir, Wilbert Rideau writes about how tightly Cain controls his messaging—a practice that had grim consequences for the Angolite, once known for its investigative reporting. At a time when even outside journalists encountered increasing barriers to access at prisons nationwide—it’s almost impossible now to interview an inmate, or even a staffer, at many state and federal prisons—the Angolite staffers found their calls monitored and their stories censored. “The only information coming out of Angola,” Rideau says, “was what Burl Cain wanted the public to know.”

When I asked Fontenot about this, she shook her head and told me that after he started winning journalism prizes and drawing attention from outside Angola, Rideau withdrew from prison life, spending all his time holed up in the Angolite offices. His celebrity, she thought, had gone to his head.

Or perhaps Rideau got on the wrong side of Cain by refusing to embrace the dominant story of the warden as Angola’s savior, a narrative neatly summed up by prison chaplain Robert Toney in congressional testimony in 2005: Angola “was once the most violent prison in America. Today, we are known as the safest prison in America. This change began with a warden that believed that change could occur.”

In fact, there is considerable evidence that the turnaround at Angola began two decades before Cain became warden, in the 1970s, when a prisoner lawsuit forced the facility into federal oversight and a series of reforms began. According to Burk Foster, a professor of criminal justice at Saginaw Valley State University in Michigan and the leading historian of Angola, by the mid-1980s Angola was already the most secure prison in the South. Prison violence is down dramatically across the country; the prison murder rate has fallen more than 90 percent (PDF) nationwide in the last three decades.

Yet the legend of Cain persists—and not just because Cain and his team (the formidable Cathy Fontenot included) are so skilled at PR. Cain does a job that no one else much wants to do, dealing with a group of people that no one else much wants to think about. Rather than face that reality, most of us prefer to believe in a miracle.

Aside from the high-level escort, my tour of Angola had covered pretty much what the tourists see, except for the closing lunch—Fontenot took me to the Ranch House, a sort of clubhouse where the wardens and other officials get together in a convivial atmosphere for chow prepared by inmate cooks. (It’s traditional for Ranch House cooks to go on and work at the governor’s mansion, but Gov. Bobby Jindal had spurned that tradition.) The house is built low, with a long porch and white board fence; we sat down to barbecue chicken, red beans and rice, and sweet potato pie, all of it quite good.

After lunch, I accompanied Fontenot to her office in the administration building. When we’d scheduled the tour, she’d promised me an interview with Cain provided he was at Angola when I visited, which she expected him to be. But when I asked, “Where’s the warden?” she said matter-of-factly, “Oh, he’s in Atlanta today.”

On the way back over the line to the free world, I asked Fontenot whether the warden might consider talking to me on the phone. She suggested I follow up once I got home, and I did, thanking her for the tour and the fine luncheon. After several weeks and multiple inquiries—including a few questions submitted via email, at her request—I got this reply:

The warden respectfully declines to participate in this article. As he says often, its all of us at Angola that have caused the positive changes. Thanks again James. It really was a pleasure to meet you in person. Stay warm during these cold days of winter.

Much peace to you,

Cathy

When I interviewed John Thompson, the exonerated death-row inmate, about his time in Angola, he mentioned what he believes is one of the public’s biggest misconceptions about prisons. Most people look at the fence around the perimeter and think its purpose is to keep prisoners from escaping. But the barrier “isn’t there to keep prisoners in,” Thompson said. “It’s to keep the rest of you out.”